The Truly Epic Story Of How The Battle Of Helm's Deep Was Filmed

"It was a microcosm of what the whole movie was about in a way," Viggo Mortensen muses in "Return to Middle-earth," a WB TV special looking back at the making of the "The Lord of the Rings: The Two Towers," the middle chapter of Peter Jackson's epic fantasy trilogy. "Just egging each other on to go past your limits. I hated it, I enjoyed it, I will always remember it."

"It was a nightmare," says Orlando Bloom.

The "it" in question is Helm's Deep, and the brutal four months that went into creating one of the most incredible battle sequences in cinema history. Hundreds of extras, stunt performers, and crew members assembled for weeks upon weeks of exhausting 14-hour shoots. The majority of these took place at night and — like the battle itself — only ended with the arrival of the dawn.

Filmmaking itself has echoes of warfare. There's a clear chain of command, descending from the producers and director to the heads of each department, and from the department heads down to their crew. Discipline, communication, and leadership are essential, and resources are finite. Even the language of film has a violence to it: "cut," "shoot," "striking." In between the action, there's an awful lot of waiting. And if morale breaks down, the results can be disastrous.

Helm's Deep had all the ingredients for breaking morale: long hours, freezing conditions, no sunlight, countless injuries, and an army sharply divided into factions. But if you've seen "The Two Towers," which premiered exactly 20 years ago today, you'll know that the Battle of Helm's Deep ultimately ends in triumph.

Here's the story of how it all came together.

Building Helm's Deep

"This is more to my liking," said the dwarf, stamping on the stones. "Ever my heart rises as we draw near the mountains. There is good rock here. This country has tough bones. I felt them in my feet as we came up from the dike. Give me a year and a hundred of my kin and I would make this a place that armies would break upon like water."

– J.R.R. Tolkien, "The Lord of the Rings"

Work on Helm's Deep began seven months before any Uruk-hai or elves arrived. The set builders and decorators settled in for the long haul at Dry Creek, an active quarry in the Wellington region of New Zealand's North Island. It's about a six-hour drive from Hobbiton (you can get there faster if you travel by eagle, but their schedules are notoriously erratic).

"A quarry by its nature is really harsh," explains supervising art director and set decorator Dan Hennah in "New Zealand as Middle-earth," one of the many behind-the-scenes features that make up the Appendices of the "Lord of the Rings" Extended Edition releases. "You have no vegetation, you have nothing to soften the elements [...] If it's a cold day, everything's wet and slippery and uncomfortable. So it was an incredibly hard place to work." Yet it was also the only location where Helm's Deep could feasibly be built, and the owners of the quarry were willing to host the production for a full year, so the challenge was accepted.

When it came to designing the architecture of Helm's Deep, the team had a lot to work with in the source material. "Tolkien's very specific," says Peter Jackson in the feature-length documentary about the making of "The Two Towers," directed by Wellington filmmaker Costa Botes. "It has the long wall, the Deeping Wall. It has the Hornburg, which is the massive keep, and the tower which houses the horn which blasts through these echo chambers."

The full version of the castle was only built at quarter scale, since building the whole thing full-size would have been impractical. This miniature version was mostly used for wider shots, which could then be used as a stage for VFX or blended with footage from the full scale sets. The ancient, unconquered fortress of Helm's Deep had a plywood base, covered with polystyrene and then plaster before finally being painted to resemble stone. Botes' footage at one point shows Jackson casually picking off a chunk of it and joking, "You can break Helm's Deep with your own fingertips!"

The unsung hero of Helm's Deep

Together Éomer and Aragorn sprang through the door, their men close behind. The two swords flashed from the sheath as one.

"Gúthwinë!' cried Éomer. "Gúthwinë for the Mark!"

"Andúril!" cried Aragorn. "Andúril for the Dúnedain!"

– J.R.R. Tolkien, "The Lord of the Rings"

Pay close attention to the behind-the-scenes footage of Helm's Deep and you may notice a conspicuous absence: that of Peter Jackson himself.

While the image of the lone visionary director painstakingly crafting every single shot in a movie is useful for marketing, where truth gets shaped into a more easily digestible legend, it's rarely the reality with movies on any scale above the very low budget. A director's time and energy is a precious resource, and it's necessary to delegate in order to keep schedules and budgets in check.

Principal photography for the "Lord of the Rings" movies (which were shot back-to-back) took place between October 1999 and December 2000 — a dizzyingly condensed schedule for three fantasy epics with an average theatrical runtime of more than three hours, made all the more challenging by the main characters splintering off into several different storylines. Jackson could not be in two places at once, and when filming lagged behind schedule, he would sometimes turn to his creative partner and wife Fran Walsh for an assist on the directing front. Among the scenes shot by Walsh in "The Two Towers" is the eerie sequence where Sméagol argues with his vindictive alter ego, Gollum.

But Helm's Deep wasn't just one short scene: it amounted to months of filming, focused largely on stunt performers and extras with only a few members of the core cast in the mix. Speaking to the A.V. Club, second unit director John Mahaffie explained that if "The Lord of the Rings" had been shot with a single unit and a single director, filming would have taken three times as long. Jackson needed to divide in order to conquer.

Mahaffie's experience up to that point had primarily been as a director of photography on smaller films, and he'd never directed a second unit before. But Jackson trusted Mahaffie, having previously worked with him on "Heavenly Creatures," and so he offered him the daunting task of overseeing the second unit for the "Lord of the Rings" trilogy. The schedule for Mahaffie's unit matched the duration of the main unit; he was effectively directing three feature films alongside the three that Jackson was directing.

Like most productions, "The Lord of the Rings" did not shoot in sequence. "When we were doing Helm's Deep, Peter was in Bag End," Mahaffie told Empire. During the day, Gandalf would be warmly reuniting with his old friend Bilbo Baggins in Hobbiton; when the sun went down, Aragorn, Gimli, and Legolas would face an army of Uruk-hai 300 miles away. Mahaffie was working towards Jackson's vision, but the buck ultimately stopped with him when it came to the logistics of filming:

"For all intents and purposes, we operate as a stand-alone unit — independent. And my role as a second-unit director is, first of all, to be in tune with the style of the main-unit director and the action requirements, and to be intuitive as to his priority for the look of the film and how the film is to go together. But then once I've taken that and I'm on set with a full crew of 120, 150 people, it's a machine that I run like any other unit."

In total, Mahaffie estimates that he directed around 90 percent of the Battle of Helm's Deep.

The army of the undead

Before the wall's foot the dead and broken were piled like shingle in a storm; ever higher rose the hideous mounds, and still the enemy came on.

– J.R.R. Tolkien, "The Lord of the Rings"

In 2014, Warner Bros. Interactive Entertainment released the video game "Middle-earth: Shadow of Mordor," in which the player takes on the role of an undead ranger whose body is merged with the wraith of an elven lord. The most innovative feature of the game was the Nemesis System; as the player roams around Mordor slaying orcs and disrupting Sauron's plans, they find themselves facing orcs that they've slain in battle before, crudely restored to life with metal plates and bandages.

More than a decade before "Shadow of Mordor" was released, Viggo Mortensen was playing the live-action version of it at Helm's Deep. Though there were hundreds of Uruk-hai extras on set, Helm's Deep had a core team of around 20 highly trained stunt performers to handle the most intense combat, and those "stunties" returned over and over again in different guises. As Weta Workshop co-founder Richard Taylor explains with amusement in Botes' documentary, "We put different helmets on them every night and just shove them back out again."

"I know that I killed each stunt person at least 50 times," Mortensen later recalled. "It went past that at some point and I just stopped counting, because it was ridiculous." Quoted in Ian Nathan's book "Anything You Can Imagine: Peter Jackson and the Making of Middle-earth," stunt coordinator Tim Wong says that he also lost count of how many times he was slain by Aragorn: "It would have been at least 50 times in the trilogy, and a couple of dozen in Helm's Deep alone."

The forces of Sauron were made up almost entirely of Kiwi actors. Many members of the core stunt team had previously worked together on shows like "Xena: Warrior Princess" and "Hercules: The Legendary Journeys," so there was an existing camaraderie between them that only deepened during their time in Helm's Deep. 6'4" stunt performer Shane Rangi, in particular, was prized for his height. He played a Haradrim warrior in the Battle of the Pelennor Fields (brought down by Éomer's spear), and shared the roles of the Witch-king of Angmar (stabbed in his ghost-face by Éowyn) and the orc commander Gothmog (tag-teamed by Aragorn and Gimli) with his fellow stuntie, Lawrence Makoare.

"I died hundreds of times," said Rangi. "We were usually cannon fodder in the hero fights for the Aragorns and Gandalfs of Middle-earth. I think I was killed by Faramir a dozen times alone in the attack on Osgiliath."

When they weren't being killed by the heroes, it was also common for stunt performers to switch sides in the war. Reminiscing about his days in Middle-earth on a podcast hosted by another "Lord of the Rings" alum, Augie Davis, Rangi pointed out the upside to being one of the faceless undead:

"When you're in stunts it doesn't matter what you are, you can play a whole lot of characters! In 'Lord of the Rings' everyone knows that Rohan were fair and blond. And yet, when the numbers were short, in we went, put on the old blond wigs. They put us way down in the back, we were the Bro-han."

The long night

Aragorn looked at the pale stars, and at the moon, now sloping behind the western hills that enclosed the valley. "This is a night as long as years," he said. "How long will the day tarry?"

– J.R.R. Tolkien, "The Lord of the Rings"

Over the three months of night shoots on Helm's Deep, tens of thousands of gallons of water hammered down onto the assembled armies: some of it from giant rain bars suspended by cranes overhead, and some produced naturally by the New Zealand climate. According to "The Making of Middle-earth," a working "day" would begin at 5pm and continue until dawn. For featured Uruk-hai, this would start with three to four hours in make-up and costume, and they'd spend the rest of the night executing stunts in armor and prosthetics that weighed 40-70 pounds (depending on the orc).

Movie stars might get more luxuries than the average stuntie or crew member, but there was no escaping the grind of the night shift. "You can see it on people's faces, how tired they were," says Viggo Mortensen in "Return to Middle-earth." When the sun-starved denizens of Helm's Deep ventured out into Wellington during the day, he added, it was easy to spot a fellow creature of the night:

"Everybody had this sort of vampire life where we were passed out from exhaustion. You got outside on the street and you're all sort of pale and scratched-up and cross-eyed, and you recognize each other blocks away, like 'There's one!'"

On set, the Uruk-hai performers would often have to stay in their regimented lines for long stretches of time, waiting to begin filming, which made for a dangerous combination with the rain and the cold night air. "Guys were falling over in their suits because they were soaking wet," said stunt performer Mana Davis. "They were so cold that they were getting pneumonia."

Yet more notable than the long hours, the lack of sunlight, the cold, the rain, and the hostile terrain was how the Helm's Deep unit rallied instead of crumbling, taking their cue from the stunt team — who, as Peter Jackson notes in the bonus feature "Warriors of the Third Age," bore the brunt of most of the shooting.

"They were the true heroes of Helm's Deep," says Jackson. "Their spirit, their energy, their enthusiasm, it just ended up giving us great material on film." Co-producer Rick Porras recalls that at around 2:00 A.M. on a particularly cold night, weeks into filming, the Uruk-hai extras who were standing in the cold began singing in a quiet chorus, "to get through the night while they were waiting for the cameras to roll."

That resilience, demonstrated by those who were suffering the most, became the backbone of morale on the Helm's Deep shoot. "I've never seen any group of stunt people take more of a beating without complaining at all," Viggo Mortensen marveled. Seeing the ranks of exhausted, battered stunties continue to give 100 percent in take after take, "you couldn't in good conscience do anything less than your best."

Made in New Zealand

"What of the dawn?" they jeered. "We are the Uruk-hai: we do not stop the fight for night or day, for fair weather or for storm. We come to kill, by sun or moon. What of the dawn?"

– J.R.R. Tolkien, "The Lord of the Rings"

Even before he made "The Lord of the Rings," Peter Jackson was one of New Zealand's favorite sons thanks to his early low-budget films like "Bad Taste," "Braindead," and "Heavenly Creatures." The production of the "Lord of the Rings" movies created jobs for hundreds of New Zealanders, and later gave the country's tourism industry a powerful boost. For the Kiwi cast and crew members who worked on it, "The Lord of the Rings" wasn't just a job; it was an opportunity to represent their national identity on the world stage.

The atmosphere on set crystallized some of the core principles of Kiwi working culture: a laidback manner, a "give-it-a-go" attitude, and a strong belief in teamwork and fairness. Craig Parker, who played the elven commander Haldir, said that Jackson led by example:

"It was very important to Peter that there was a familiar atmosphere and a pleasant working climate. I never witnessed him lose his calm. I am sure he was pulling his hair several times. But on set he was always calm, friendly and attentive. I always had the feeling he enjoyed being there and was glad to make the movie. And the conditions under which people had to work were sometimes so hard that it was the only way to finish this movie. And it paid off: Not a single actor ran away in the middle of things and acted like a primadonna, with terrible migraines and the likes!"

Early on in his weapons training for the films, Viggo Mortensen heard one of the swordmasters utter the phrase "adapt and overcome." It became a mantra; he wrote the words on a note and pinned them above the mirror in his trailer. Over and over in interviews, the actor describes how awed he was by the work ethic of the Kiwi stunt performers and extras. "Even in the background they weren't fooling around," he said. "We had people fifty or one hundred yards away looking like they were getting killed. If one department even hinted at letting up, the other departments would shame them back into focus."

But while there was certainly peer pressure to not complain about the long hours and harsh conditions, the true spirit of Helm's Deep was one of brotherhood. "If someone was going through pain, or going through their own little troubles in their head, someone would be there to pat them on the back and [say], 'come on, bro, you can do it!'" said stunt performer Mana Davis.

"We had a great bond," agreed Sala Baker, who portrayed Lord Sauron himself when he wasn't playing one of Sauron's many minions. "It was exactly what you'd think a war would be like, because you had the wall exploding, you had the fighting, you had the long nights of sitting around and waiting for certain things to happen."

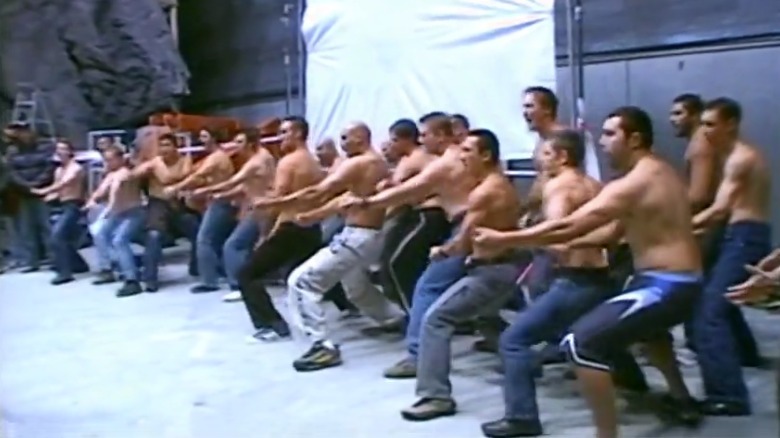

The behind-the-scenes feature "Cameras in Middle-earth" reveals just one of the ways in which this sense of camaraderie shaped the Battle of Helm's Deep. One night, to help keep themselves warm and sane while they waited for the cameras to start rolling, some of the Uruk-hai performers began to tap the ends of their spears on the ground. The action rippled out until scores of orcs were rhythmically pounding their spears into the mud. Seeing this, second unit director John Mahaffie was inspired to incorporate it into the battle, and the spontaneous spear-pounding became an intimidation tactic used by the Uruk-hai ahead of their charge on Helm's Deep.

Orcs vs. elves

"Hark! They hate us, and they are glad; for our doom seems certain to them."

– J.R.R. Tolkien, "The Lord of the Rings"

The stunt performers and extras may have played both sides elsewhere in the war, but at Helm's Deep they were mostly divided up into the armies we see in the battle. And after weeks of night shoots, the lines between fantasy and reality began to blur. "Pretty much everyone nearly lost their marbles," said Orlando Bloom.

According to Ian Nathan's "The Making of Middle-earth," the Uruk-hai actors were seized by a longing for victory, despite knowing that they were scripted to lose. The battle lines held strong even when the cameras weren't rolling. "We orcs stuck together," declared Shane Rangi, elaborating:

"You had your Elves on one side and your Uruk-hai on the other, and at lunch it was exactly like that as well. It was because you'd spend twelve weeks out at the quarry, working five or six days a week, fourteen hours a day. You would form a close bond with those people. And you tended to find that the Elves were quite tall and pretty and prissy, and the Uruk-hai were all rugby league players, quite hard. We were all out there suffering, but only the Elves made their misery known, and we didn't want to be associated with the whingeing!"

Unlike the Uruk-hai forces, which were largely made up of indigenous Polynesians and Pacific Islanders with muscular frames and the grit needed to stand in the rain for hours wearing heavy padding and prosthetics, the casting requirements for Haldir's army of elves from Lothlórien were less demanding: they simply needed to be young, tall, and thin. Many of the elven extras were students in their late teens or early twenties, for whom this was their first experience on a movie set. It quickly became apparent that they didn't know how to march, and so they had to be taken through some hasty training by ex-military members of the crew and cued with hand signals to keep them in step with one another.

In "Warriors of the Third Age," John Mahaffie reveals that the frisson of hostility from the Uruk-hai actually helped the elven extras get into the fighting spirit. "They were a little bit reticent to show the same aggression [as] the team of stunt boys and the Uruk-hai, who'd been with us as a team for some time," he said. At one point when the crew were focused on filming the elves, the Uruk-hai performers behind the camera began to taunt the fair folk.

"They began to get their weapons and they'd start smacking them against their chestplates," said Weta Workshop's Richard Taylor. "And chanting at the elves, teasing them, taunting them, and jeering at them, just like you would in war, you know? 'Ah, yer mother!' And really winding them up." This eventually morphed into a Māori haka, a traditional dance accompanied by fierce chanting.

The elven performers had, at the time, their bows cocked with arrows preparing to fire down at the Uruk-hai, and the taunts made their blood rise. "We didn't realize it was shooting while they were doing it, we just thought they were giving us a lot of flack," said Mana Davis, who was fighting on the side of the elves that day. "So some of us started going back at them, 'Ka mate, ka mate!' and doing all that [mimes haka body-slapping]. The next thing we heard, 'cut!'"

"We had a few modern-day gestures creep into the program there, and we had to cut," stunt coordinator George M. Ruge explained, laughing.

'I am no man!'

Then the prince went from his horse, and knelt by the bier in honor of the king and his great onset; and he wept. And rising he looked then on Éowyn and was amazed. "Surely, here is a woman?" he said. "Have even the women of the Rohirrim come to war in our need?"

– J.R.R. Tolkien, "The Lord of the Rings"

Amid all that testosterone-fueled machismo, you might be wondering if there were any women at all among the stunt performers and extras at Helm's Deep. After all, the "Lord of the Rings" trilogy doesn't exactly have an abundance of female characters; it's pretty much just Galadriel, Arwen, Éowyn, and everyone's favorite girlboss, Shelob.

Miranda Otto's Éowyn was at Helm's Deep, of course, and along with the rest of the cast and stunties she was trained by legendary swordmaster Bob Anderson, who had once crossed swords with Errol Flynn. He told this anecdote to "Lord of the Rings" stunt performer Lani Jackson, who later called her mother to ask, "Who's Errol Flynn?" (She might have been a little more impressed had Anderson mentioned, for example, that he was inside the Darth Vader costume for all of the lightsaber battles in the original "Star Wars" trilogy.)

Jackson was the stunt double for Liv Tyler, who shot scenes at Helm's Deep that ultimately ended up being cut from the movie. But that wasn't the end of Jackson's time on the battlefield: she was a core member of the "Lord of the Rings" stunt team, and when she wasn't wearing Arwen's clothes, she was being covered in prosthetics and padding to play goblins or Uruk-hai. "Lani could do all the different stunt roles needed, even though she wasn't as big as some of the other guys," says co-producer Rick Porras in the "Warriors of the Third Age" featurette.

To return to Shane Rangi's point, this was one of the upsides to being a stuntie or a background performer: there were fewer limits to which characters you could play. Rangi, a bald-headed Māori, could play one of the fair Riders of Rohan with their long, flowing blond locks. And if you look closely at the Riders of Rohan, you might notice that some of them are particularly fair. In behind-the-scenes footage from "The Two Towers," Peter Jackson is seen getting the Rohirrim hyped up to start filming. "Your blood's up, you're men of Rohan," he calls to them. "Even the bearded ladies are men of Rohan today."

Yes, Éowyn isn't the only woman who made her way into battle using the most basic of disguises. Finding extras who were confident horseback riders was a challenge, especially since the producers ideally wanted to recruit people who owned their own horses. With a professional makeup team at the ready and plenty of fake beard hair, there was no reason to restrict casting; Peter Jackson needed every skilled equestrian that New Zealand had to offer. Many of the Riders of Rohan you see on screen are women, indistinguishable from the men thanks to their layered costumes (and, of course, their beards).

By contrast, the hulking Uruk-hai at Helm's Deep were made up mostly of male stunt performers, with Lani Jackson being one of the most prominent exceptions. Rick Porras (who also did bits and pieces of directing on the films) said that one of the reasons he liked working with Lani was the way she would disappear into the chaos of battle ... right up until the moment that she yelled. "You'd have these moments with all these different Uruk-hai getting killed and hacking and slashing," Porras recalled with amusement. "But you always knew where Lani was, because of her voice."

"The stuntie men are going 'grrr-rrr-rrr-rrr' and then I'd be in there, 'aah-aah-aah-aah!'" Jackson elaborates.

Although her voice never quite matched the pitch of the other Uruk-hai, joining their ranks had a transformative effect on her body. In Helm's Deep, there's no such thing as skipping leg day. "Prior to Helm's Deep I had nice female legs," Jackson says wistfully. But after twelve weeks of night shoots in 40 pounds of padding, armor, and prosthetics, "I had tree trunks! Where were the nice legs? I was like, 'Oh my god!'"

Casualties of war

"The men of Rohan grew weary. All their arrows were spent, and every shaft was shot; their swords were notched, and their shields were riven."

– J.R.R. Tolkien, "The Lord of the Rings"

With the number of battle scenes, stunts, and general cavorting around in the New Zealand countryside, accidents and injuries were inevitable during the making of the "Lord of the Rings" trilogy. Perhaps the most famous example is Viggo Mortensen breaking two of his toes when Aragorn kicks an orc helmet to express his grief, thinking that Merry and Pippin have been killed (the take, complete with Mortensen's scream of agony, made it into the movie).

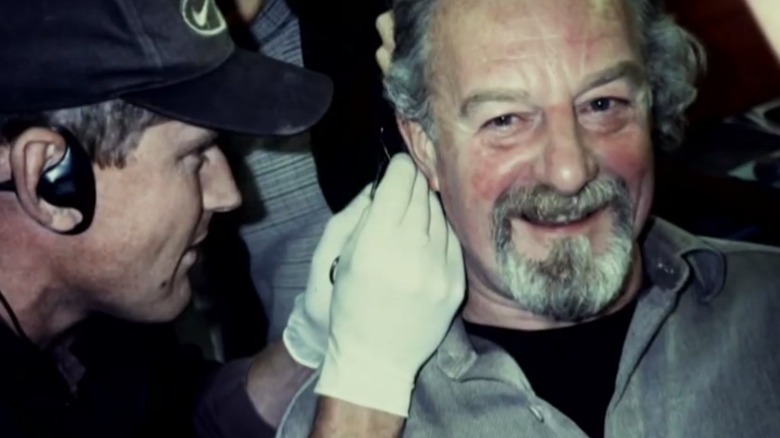

Another legendary Mortensen injury occurred during the fighting at Helm's Deep, when he was accidentally smashed in the mouth by a protruding fin of Uruk-hai armor, breaking off a large chunk of his front tooth. Mortensen simply picked up the tooth and asked if anyone had any superglue so they could stick it back on and continue filming. He was whisked away for emergency dentistry instead, but went straight back to the set as soon as his tooth was presentable again.

Asked about the incident in an interview for "Cameras in Middle-earth," Mortensen seems almost embarrassed by the fuss over one silly little tooth. "That was like business as usual for everyone involved," he insists. "And it's only because it's an actor that it's even mentioned."

He's not wrong. A broken tooth was far from the worst injury incurred at Helm's Deep, where cuts, bruises, and sprains were a nightly occurrence. The set may have been made of plywood and polystyrene, but the weapons and armor were made of metal and could do a lot of damage, even with the edges blunted. In behind-the-scenes footage, stunt performer Sala Baker is shown introducing himself by the unit's mobile medical vehicle. "Hi, I'm Sala, I'm a stuntie, and the reason we're here today is because of..." He drops his head forward with a flourish to show the metal staples holding his scalp together, the result of being whacked on the top of the head with a sword. "This!"

Everyone went all-out in the battle scenes. Uruk-hai performer Kane Bixley told NME that "the fighting was almost real," and in particular recalls a moment when "some guy ran up to me and knocked me down during the Helm's Deep battle, and kept hitting me with a spear while shouting, 'That's gotta hurt!'" The battering ram used by the Uruk-hai to break down the gate was also real: a section of utility pole made from solid wood. One of the Uruk-hai performers who wielded it, Clinton Ulyatt, told Red Carpet News: "I remember going home that day, running a bath, falling into it and waking up about six hours later with no water around me,"

Viggo Mortensen was determined to do as many of his own stunts as possible, and was also dedicated to hitting as hard as he could in combat. "As a stuntie, you want to fight Viggo, because you know he'll give it as much as you will, and he'll take it as well," says Augie Davis in the "Warriors of the Third Age" featurette. "When you're in a fight with him, you feel like you're in a real scrap." A photo taken by makeup artist José Péréz in the aftermath of the battle shows Mortensen's hands covered with bloody divots, chunks taken out of them by glancing blows with swords and armor.

Mortensen wasn't the only key cast member left scarred by the Battle of Helm's Deep. Brett Beattie, the stunt double for John Rhys Davies (and the Gimli you'll see on screen pretty much any time that Davies' face isn't clearly visible), told Polygon that he suffered two blown knees during the making of the trilogy. When he went for his third reconstructive knee surgery in 2021, the surgeon asked him how the injuries had occurred and Beattie replied, "Well, I was battling Uruk-hai at Helm's Deep."

And it wasn't only their enemies that the warriors of Helm's Deep had to worry about: Théoden actor Bernard Hill suffered some friendly fire. "I got hit by my own assistant," he recaps in footage filmed after the incident. "Gamling [Bruce Hopkins] whacked me on the ear with his sword. Somebody fell on his arm and his sword went 'crack!'"

Perhaps the most innocent casualty of Helm's Deep was poor Orlando Bloom, whose injury was an indirect result of the battle. Over the course of the grueling four-month shoot, Viggo Mortensen became a sort of honorary member of the stunt team and developed a unique way of bonding with his stuntie friends (particularly after they'd been doing shots at the bar). It went like this: Viggo would clasp the person's face, look deep into their eyes, say something sweet to them ... and then head-butt them as hard as possible.

"We'd be in the bar having a drink and he'd be like WHACK," Lani Jackson recalls, with a wince of remembered pain.

"It does seem silly now, in retrospect," Mortensen later admitted. "A bunch of grown men going around head-butting each other anywhere they encountered each other." But at the time, he was keen to spread the love. At the premiere of "The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring," which took place while pick-ups and reshoots for the sequels were still ongoing, Mortensen managed to convince Sala Baker that it would be a great idea to head-butt an unsuspecting Bloom. In an interview for the "Lord of the Rings: Extended Edition" Appendices, Baker recalls:

"Viggo goes, 'Do it. Do it. Do it.' And I was like, 'Hey, Orlando, bro — I love you, dude.' WHAM! And I got in trouble because the next day makeup was like, 'Why does Legolas have a big red dot on his forehead?'"

Bloom only remembers a burst of white light and wondering if he had gone permanently blind. "Now, every time I see [Sala]," he says, with a haunted expression. "I see the white light."

Appendices

In the final weeks of the shoot, T-shirts were distributed to members of the Helm's Deep cast and crew with the slogan "I survived Helm's Deep." The internet being what it is, you can buy custom-printed copies of this shirt from various online retailers. But to wear the T-shirt without having survived Helm's Deep — the Helm's Deep of Dry Creek Quarry, and all the exhaustion and elation of those four months — might fall under the definition of stolen valor.

"[Helm's Deep] was the maker and breaker of certain people," declares Sala Baker in the Appendices for "The Lord of the Rings: The Two Towers" Extended Edition. A battle sequence on that scale, requiring that much of a time commitment and involving that many people, has rarely been attempted across the history of cinema. "Everybody earned their stripes on that, on Helm's Deep," Viggo Mortensen said solemnly, looking back at the experience.

Great careers were forged in the fire of Helm's Deep. While his name may not be as well known as Peter Jackson's, John Mahaffie went on to become a go-to second unit director for some of Hollywood's biggest projects, shooting major setpieces for the "Chronicles of Narnia" movies, Marvel pictures like "Spider-Man: Homecoming" and "Avengers: Age of Ultron," and DC films like "Shazam!" and "Aquaman."

Sala Baker moved out to Los Angeles and also got into the Marvel Cinematic Universe game, performing stunts for "Iron Man 3" and "Captain America: Civil War," and playing the adult version of Firefist in "Deadpool 2." He sparred with Robert Downey Jr. in "Sherlock Holmes: A Game of Shadows," and played a Klatooinian Raider Captain in "The Mandalorian." "I just hustled my way through America," he explained in a 2019 interview.

Brett Beattie gathered up his busted knees and bravely returned as a stunt performer for the "Hobbit" movie trilogy, alongside Shane Rangi, Augie Davis, Mana Davis, Tim Wong, and various other veterans of Helm's Deep ("The Hobbit" was basically a big family reunion for the "Lord of the Rings" cast and crew).

Viggo Mortensen recently starred in rescue drama "Thirteen Lives," proving that he has not mellowed or started favoring less physically demanding roles in the days since Helm's Deep. The "Thirteen Lives" shoot involved swimming through flooded tunnels with no easy way to come up for air. "Two feet above you is just rock, and you better get through this passageway or you're not going to come out," he told Entertainment Weekly:

"It was time consuming, energy consuming, but all the actors wanted to do it. We spent countless hours underwater. I was sad when I said goodbye to the last tunnel and eventually took my gear off and had to turn in my harness and my tanks. I was like, 'These are my friends.'"

As of 2016, Mortensen was still spontaneously head-butting his "Lord of the Rings" co-stars.