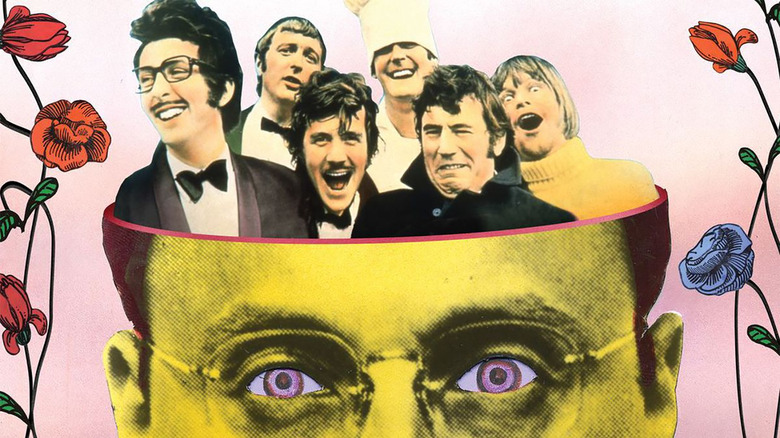

John Cleese Remembers Monty Python As A 'Democracy Run Riot'

The writing of "Monty Python's Flying Circus" was largely handled in teams. John Cleese and Graham Chapman would write sketches together, and their output tended to be more linguistic and cerebral; Cleese and Chapman were responsible for the Cheese Shop sketch, for instance, or the Argument Clinic. Michael Palin and Terry Jones were a team, and their sketches tilted toward whimsical absurdity; the pair wrote the Spam sketch and the Dead Parrot sketch. Eric Idle wrote sketches on his own, and his tended to be cheeky, as when he wrote the "Wink wink, nudge nudge" sketch. He also wrote the show's songs. Terry Gilliam lived off to the side working on the "Flying Circus" animations.

As stated in any number of retrospectives, the team would then unite to pitch and/or read sketches. Together, they would hone the jokes, make them as funny as possible, and agree as to who would play which parts. Graham Chapman, Cleese once said, was expert in throwing in jokes from the sidelines, often improving a sketch with a single bon mot. Most "Monty Python" retrospectives also detail how Cleese and Jones would deliberately goad each other into arguments, and a lot of fighting — not always good-natured — would take place. Overall, however, there was no single arbiter of sketch selection, with the whole group generally agreeing on what would and wouldn't make it into the show.

This was certainly the way Cleese remembered it, as he once said in a 2014 interview with the Harvard Business Review. He recalls very sharply that the show was handled democratically. Like King Arthur and his knights, the table was round and no one sat at the head.

'Is it funny or not?'

When asked about the decision-making process, Cleese was quick to point out their Arthurian philosophy, saying:

"Python always was democracy run riot. There was no senior person, no pecking order, no hierarchy. It was always a question of reading things out, and if they made people laugh, they were put in the show. If people didn't laugh, they almost certainly weren't. That was the litmus test. Had we been trying to portray a philosophy or something like that, there would have been much more argument."

It likely helped that Python had already affected the philosophy of meaninglessness. They were devoted to absurdity and had given themselves a stringent mandate rejecting punchlines. Comedic scenes would drift into one another, link up, peter out, or sometimes stop abruptly. They played improvised jazz, with upper-crust British manners as their instrument. There is an element of social satire in a lot of "Flying Circus," but mostly it gains its power through silliness.

When bigger ideas did float through the troupe, it helped that the six members held very similar ideas. Cleese points out that writing the 1979 feature "Monty Python's Life of Brian" — a satire of Biblical epics as well as a jibe at Christianity — no one had to bicker. In his words:

"When we made 'Life of Brian,' which I think is definitely our best work, it just happened that we all pretty much agreed on what religion wasn't. If we'd tried to agree on what religion should be, we would have always been arguing and unable to reach a common viewpoint. When you're dealing with humor, it's very simple: Is it funny or not?"

"Life of Brian," to editorialize, is uproariously funny.

Writing in pairs

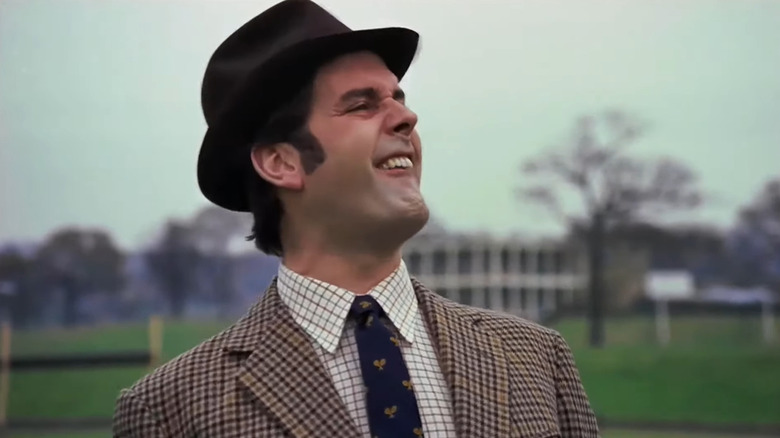

Whether or not working with the other Pythons taught him this philosophy, or whether it was a belief he held since a youth, Cleese always has believed that comedy works better with partners or in groups. Prior to "Monty Python's Flying Circus," Cleese was part of the ensemble of the 1967 sketch comedy show "At Last, the 1948 Show" as well as a regular on the 1964 radio comedy "I'm Sorry, I'll Read That Again," both hilarious in their own right.

Cleese understands that creative people make each other more creative, and that having a friend or a colleague can create better work that either individual together. He said:

"I do believe that when you collaborate with someone else on something creative, you get to places that you would never get to on your own. The way an idea builds as it careens back and forth between good writers is so unpredictable. Sometimes it depends on people misunderstanding each other, and that's why I don't think there's any such thing as a mistake in the creative process. You never know where it might lead."

In recent years, Cleese, 83, had affected an unusual stance about "edgy" humor, often railing against comedians being "canceled." This is unusual, as Cleese rarely operated out on the edge. His humor was always very writerly and character-based. When he made jokes about World War II, for instance, as he often did with Python or when Basil Fawlty shouldn't mention the war, it was always clearly at the Nazis expense, or perhaps at the expense of a fool like Basil. Cleese was never a "bad boy" of comedy, and it's quite strange that he should feel a passionate need to leap to their defense.

But at least we'll always have Monty Python.