Brian Tyree Henry Used His Understated Performance In Causeway To Reconcile His Own Grief [Exclusive Interview]

"Causeway" has been getting plenty of awards season attention, largely thanks to the fantastic performances by Jennifer Lawrence and Brian Tyree Henry. Directed by theater and TV director turned filmmaker Lila Neugebauer, the film tells the story of Lynsey (Lawrence), a soldier who has arrived back in her New Orleans home after suffering a traumatic brain injury while on duty in Afghanistan. Impatient to recover and return to duty, she strikes up a friendship with James, a local mechanic who has experienced a tragedy of his own. Rather than finding the kind of romance that typically comes from indie film festival and awards season fare like this, the two instead forge a meaningful friendship that helps each of them discover how trauma and grief are holding them back from being truly happy.

Recently, /Film got the opportunity to speak with Brian Tyree Henry ("Eternals") about his understated yet powerful performance as James. It's Oscar-worthy without feeling like a showy performance that's striving for awards. I asked the "Atlanta" actor how he gets ready for a role that is meant to be both ordinary and yet extremely tragic. Henry opened up about how his preparation for "Causeway" allowed him to come to terms with his own grief, not to mention reconciling some of the duress that came from the experiences of previous characters he's inhabited.

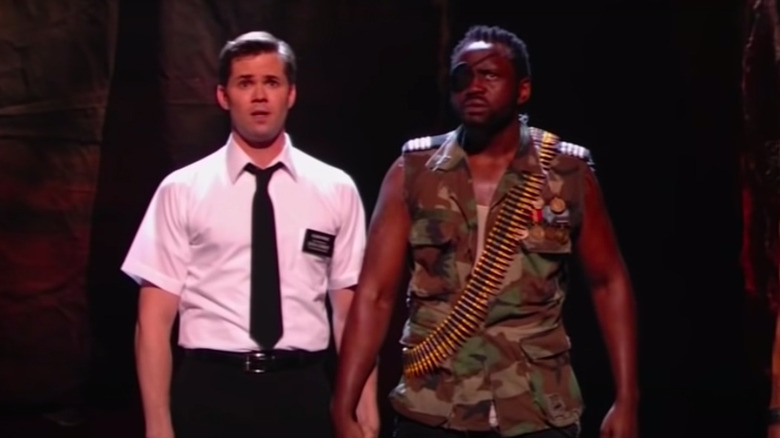

On a lighter note, did you know he starred in the original Broadway production of "The Book of Mormon" with Josh Gad and Andrew Rannells? Because he also reflected on that life-changing opportunity as well. Check out the full interview below.

'The moment that you start interacting beyond our own wants and needs, we start to become performative'

I got to see "Causeway" in theaters a few weeks ago at the Chicago International Film Festival, and I loved that your performance is so understated. It's not a big showy role. I wanted to start off by asking what was your personal preparation like for this role? Do you visit trauma centers? Do you meet with people who have shared backgrounds that kind of echo your character's story? How do you go about crafting performance that's both intensely tragic, but intended to be very ordinary?

Well, that's a great question. First, I'm an observer. I try to interact as little as possible when researching a role, because I like to observe. The moment that you start interacting beyond our own wants and needs, we start to become performative. So I wanted to make sure that I was just observing people who were dealing with being amputees and dealing with being disabled. Also, I realized that in doing that, most people who are considered disabled don't want you to draw attention to it. You know what I mean? There's a sense of wanting to be ordinary, for lack of a better word. There's a sense of wanting to blend in that way. So I made sure to just observe and respect that honestly.

Because of the kind of injury and amputation that James has, when someone suffers an amputation like that, they walk normally. They move normally. We live in an age where things are crafted to help amputees move, and like I said, for lack of a better word, in a normal way. So what I wanted to really do when I was in New Orleans was to visit someone whose job it was to make prosthesis. So Lila and I decided to go to a doctor in New Orleans whose job has always been to make prosthetics. It was kind of amazing to go into this doctor's office because it, in essence, was like a time capsule. He had been doing this for so long. So I was like, "Oh, I think that this is the guy who does all the prosthetics of central New Orleans, right? I think this is the guy. This is definitely who James came to."

So when we talked to him, he let us know, because of the amputation, which is below the knees, you still have the flexibility of your knee, so you would get this kind of prosthetic, which was like this metallic bar that simulates a shin, and then it locks into this sleeve. So there's all these different things I had to think about, because I was like, "Okay, so wait, you put a sleeve on first. You have to make sure it's underneath this kind of joint. Then you lock this leg in, which is a straight leg, which means you have to stand up this way, and then you even have to think about the color of your foot." And I was like, "Oh, s***. Right. You kind of want it to match [your skin color.]" And then I was like, "Well, also, you can't really wear socks with this because there's no skin, really."

Then [I thought about] what that must have meant for James and how his life had changed, where he had never needed to come into this doctor's office ever, because he had both legs. He walked down the street here, he learned how to walk in New Orleans. This was his home. And how he had to come in and sit in front of this doctor and hear how this is what he would have to do for the rest of his life. So when you meet James in this movie, he's already adapted to that. He's already given the appearance that he's an ordinary guy by all means. He shows up to fix this truck for this woman who needs his help. And not only that, we see him driving. You know what I mean? We see him in all instances pretty much living a normal life.

'I wanted to understand where I was going through my own personal grief...'

So for me, what I realized I needed to really unpack was what it took for him to get there. That was always something that I had to carry around, because technically that is what James is doing. He is always carrying around a reminder of how he got there. There's this thing that amputees have called the phantom limb syndrome, which is basically, for a long period of time, even I think for the rest of your life, you feel like that limb is there. You are always feeling like that appendage is still there. You can even feel it tingle sometimes. I even think I saw one person rub an area on their other leg, rub the shin of their other leg, and they could feel that feeling on the shin of the other leg that was missing. I was like, "Wow, that is really crazy how the mind does that," but also how hard that must be. And I kind of see the metaphor between phantom limb syndrome to that of grief and loss.

When you lose somebody, it is so permanent, and your mind can't really wrap your brain around that. You constantly still think and move and act as if though that person still exists. I still, to this day, oftentimes look at my phone and think to call my mother, and I'm like, "Wait, I can't do that. She's no longer here." We still save voicemails. We still leave rooms the same way that these people once lived in as a way to hold on to them, right? So I found, with James, that he was doing the same thing. For James to have suffered a huge car accident the way he did that resulted in him losing his limb and losing a life, he still drives around. He still works as a car mechanic. This man is still fixing cars for people and he still lives in the same home that was once inhabited by these people that are no longer there.

I think I took this part because I wanted to understand that. I wanted to understand where I was going through my own personal grief, doing the things that I did, how I was carrying it with me, and the way in which I carried it. Because when you're in grief, there's two things that can happen: You can either live with the grief or you're surviving with the grief. I feel like we meet James in a place where he was surviving with the grief for so long, and it wasn't until someone like Lynsey came along where he actually saw a glimmer of hope that he could live with the grief and move beyond that.

So I really wanted to understand what that was. I didn't want to go in with any kind of judgment of James being in the place that he was at, because by all means, I'm like, "Why did he stay in New Orleans? Why didn't he leave? Why is he still driving? Why is he still working at a mechanic shop? Why didn't he move?" I couldn't go in it with all those things because I'm sure people on the outside looking in are looking at me the same way, being like, "Well, why isn't Brian confronting his grief the way that he should? Why isn't he talking about his losses the way he should?" In essence, James was really helping me figure out that mindset of that kind of strength, that kind of resiliency, and that true human connections are still possible beyond grief. I think that is a big part that I wanted to display as well, not just for his healing, but for my own.

'I want people to hope for something for these guys. I want for people to care about them'

I'm glad you brought that up, because I was curious about handling these kinds of roles, as well as other roles you've had that are very existential and deal with certain crises and coming to terms with grief. Can it be hard to let go of those characters? It feel like, inevitably, those characters become part of you, not just because of inhabiting them and feeling their pain so intimately, but because like you said yourself, you had experience feeling similar kinds of pain and struggles.

Yeah, that is something that I'm still trying to learn. I do remember, especially during 2020, I was sitting alone, and I was in isolation, and these characters were still on me, man. I was like, "Oh my God, I never really released them." Because there's a thing that I really hope for when people see my performances, and what I really want is for whatever minute that you turn the television off, or you leave the theater and you sit in your car, or you leave the room where the television was to get a drink of water, that you just stand there and go, "Man, I wonder if he's okay. I wonder if that guy that I just watched, if that character is all right, like I really hope this." I want people to hope for something for these guys. I want for people to care about them.

I think that, in turn, is why I keep them close to me. Because if no one else is going to care about them, I want to make sure they know that I care about them. The trick about that is, though, it doesn't leave a lot of room for Brian to care for himself. I think that's why James was so important, because James taught me how to truly let go, how to really move beyond thinking that your identity has to be lost and that your identity has to be guilt and grief. James gave me a place to truly identify as something more than this vessel to take on the weight of these men. There's a particular scene where we're in my home, where Lynsey is sitting across from me, and then you hear James just say, "Move in. We can smoke together. We can make coffee in the morning. We can do these things." And that really came from a place of what Brian really needed and wanted as well.

Absolutely.

I didn't want to constantly move through my career carrying the weight of the loss and grief of these characters I played. I also was in a place of trying to figure out identity. I was like, "Oh, well, I'm in this show called 'Atlanta' that is funny, but at the same time, I'm doing episodes that are about losing my mom. I'm being shot at. I've got a tractor falling on me." There are all these different things. There's this kind of state of duress that my character, who is part of a comedy, is still dealing with, these kind of really heavy soul-searching moments. It wasn't until I got the chance to stand in the place where James was that I actually felt like I could release that. It is a constant learning curve. It really is. I'm still constantly trying to learn how to release, but I think that's a lifelong thing. I think that's no different than surviving grief, right?

For sure.

There is no guidebook, there's no rule book. There's nothing to tell you that this is how you're going — there's the stages of grief, right, but there's no telling what stage you're going to jump in and out of at any given point in time. So I find that if I allow myself to continue to be a channel for these stories, for these men, for these Black men, then in some way, it will hopefully give a release to the same person watching it. I did this movie also as a way to kind of showcase to myself that there is another side. There is a way to make a connection. There is a way to let go. Playing James really did help with that. I'm in a completely different place. There's still a ways to go. But I wanted that so much for myself, more than I wanted it for James. But at the same time, I felt like both of us got the release we needed.

Yeah, I hear you. I love that.

'I got to say 'f**k' at the Tonys. I'll never forget that'

I wanted to switch gears here as we wrap up, because today I learned that you originated the role of The General in "The Book of Mormon" in its first run on Broadway. That blew my mind, because I never got to see that original iteration in-person. So I was just curious, what was it like being part of that phenomenon? Have you ever reunited with Josh Gad and Andrew Rannells to reminisce about those days?

Yeah, yeah, I still talk to those two a**holes. It's funny because Josh was just in Australia, where I was, and we had connected via insulting Zoom calls. We just sent each other insulting videos, but there's so much love there. It was kind of a once in a lifetime kind of thing.

I had always respected musicals, but I never saw myself in one. That's just a certain discipline that I wasn't sure that I had. But when Trey Parker and Matt Stone ask you to be a part of their musical, you say, "Yes." I was truly influenced by "South Park." I remember watching "South Park" when it aired. I sat in front of the television on the phone with my best friend. I quoted Cartman. I went to the movies. I thought they were geniuses. I thought they were geniuses in how they could really take what was going on in real life and make it a satire and make it just as filthy, but also just as timely. So when I heard that there was a Mormon musical coming out that they were doing, and they wanted me to play the part of The General, I had to say yes.

It's also one of those instances where you're standing in the middle of something and you don't really know exactly what is going to happen. You take this leap of faith, and I never thought that it would blow up the way it did. I never doubted that it could, but I just wasn't thinking about it at the time. I was like, "My character is saying f*** every night on stage in front of a Broadway community that isn't used to hearing 'f***' on stage." You know what I mean? Like, I get to blow a dude's brains out on stage every night and say, "F*** you, God," on Christmas. What are we doing?!

It was an experience that truly, truly helped me grow, man. The people that I met in this, it changed my life. It helped me understand collaboration, because it was a true collaborative piece that we did. I got to work with some of the greats. It's the hardest thing I think I've done, as far as stage is concerned. Everybody who does a Broadway musical deserves some kind of accolade, because it is hard. It is really hard to do eight shows a week, six days a week, and "Book of Mormon" created a phenomenon even before "Hamilton." People were in the streets. You had to block our streets off, and the ticket raffles were crazy. It was everywhere. So I'm really honored. And it also gave me the opportunity to perform at the Tonys. I got to say "f***" at the Tonys. I'll never forget that. They had to bleep me on the Tonys. It was a crazy thing. But yeah, man, it was truly a life-changing experience and one I'm truly grateful for.

Do you think you'd ever want to do a live-action musical movie?

It's not off the table, man. It's not off the table. You might be surprised soon.

"Causeway" is streaming now on Apple TV+.