Aaron Sorkin Never Felt Like He Got The Newsroom Right

For three seasons, "The Newsroom" walked the slimmest of tightropes as an idealistic drama about the teams behind broadcast news. On the one hand, it needed to balance the hefty cynicism directed at media networks for their blatant partisanship and ivory-tower elitism (which it attempted to do by shaping news stories both behind the scenes and in front of a teleprompter). But the show also needed its characters to be convincingly altruistic without coming across as frustratingly naive or, perhaps worse, condescendingly didactic.

Finding such sweet spots in high-tension drama and humanistic optimism has long been creator Aaron Sorkin's bread and butter as both screenwriter and director — from "A Few Good Men" and "Charlie Wilson's War" to the "Trial of the Chicago 7" and, of course, "The West Wing." He's even been known to dip out of politics to examine everything from underdog baseball teams to deeply-flawed tech giant CEOs and the crumbling relationship of American television's most famous sitcom couple.

Despite being the third show he's created about live television, "The Newsroom" presented challenges unlike anything Sorkin had encountered on "Sports Night" or "Studio 60 on the Sunset Strip." The series would often end up resembling more of a volatile seesaw than a graceful funambulist, as Sorkin himself would be the first to admit.

A case of mistaken impressions

In a November 2020 interview with Vanity Fair, Aaron Sorkin got candid about some of his biggest projects, none more so than "The Newsroom." The multi-hyphenate admitted he never fully realized his lofty ambitions for the show and was left heartbroken by its frustrating shortcomings. "I was never able to get it quite right. I always felt like I was — like I had a pebble in my shoe," Sorkin explained. "I felt like I could write a good scene, I could put a couple of good scenes together."

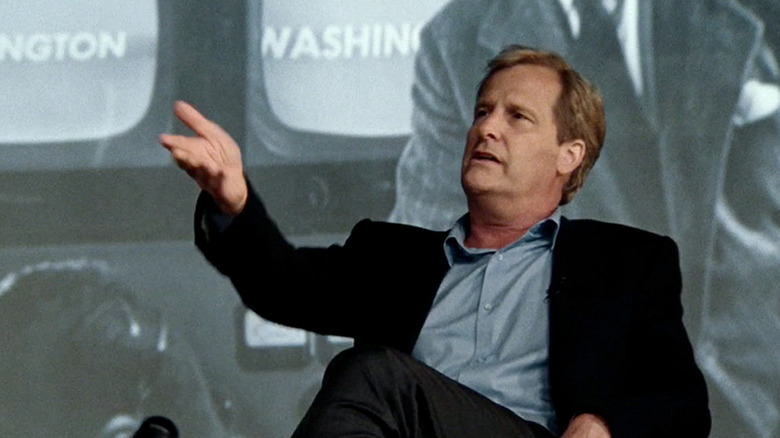

And that he could, though it helped to have a phenomenal cast fueling those scenes. At its best, the show revolved around fiery personas created by cast members like Jeff Daniels, Emily Mortimer, Sam Waterston, and Dev Patel. But those glimpses of the show Sorkin wanted to make were drowned out by the show he accidentally made instead. "Without my realizing it," he admitted, "I was giving a mistaken impression, beginning with the very first episode — two mistaken impressions." Those impressions were consequences of two crucial pieces of the show. The first was Will McAvoy's railing monologue against American exceptionalism in the pilot, and the second was Sorkin's decision to use the fairly recent past as the series' setting.

America is not the greatest country in the world

The opening scene of "The Newsroom" was designed to be the inciting incident for much of what happens involving Will McAvoy's character development. It's also one of the only scenes that ever seems to be circulated of (and as a result has become synonymous with) the show. And taken out of context — even if you agree with all of McAvoy's salient points — it feels quite self-righteous. This was the first mistaken impression that Aaron Sorkin admitted to Vanity Fair that started to take hold regarding "The Newsroom."

In reality, the scene is far less about McAvoy's shockingly acerbic answer to the equally maddening question of "What makes America the greatest country in the world?" and far more about the circumstances that led to it. Sorkin explained that the scene he was trying to write was one "about a guy having a nervous breakdown" in the middle of a Q&A at Northwestern University because he's "not doing the kind of thing he knows he should be doing, he's selling out a little bit." In this particular case, he's "selling out" by dodging all the questions directed at him and staying silent while his fellow panelists (a liberal and conservative) vainly duke it out.

On top of that, McAvoy thinks he sees his ex-lover and veteran reporter MacKenzie McHale holding up cue cards from the onlooking crowd. This ends up being the final push he needs to drop the facade he's created out of a need to be liked by colleagues and audiences alike to actually speak his mind. Like Howard Beale's famous speech from "Network," this was intended to be McAvoy's "I'm mad as hell" moment — not Sorkin "lecturing America on what was wrong with it."

Real news or fake news?

The second mistaken impression Aaron Sorkin believes he created about "The Newsroom" was that it was a sort of revisionist version of the news reported on between 2010 and 2013. "I think that there was a feeling that I was trying to show the pros how it ought to have been done," he told Vanity Fair. "That we're going to do this again, only we're going to give it the 'West Wing' treatment, where honorable people are doing it right — obviously leveraging hindsight. And I wasn't trying to do that."

The reason he used fairly current events as his breaking news pieces was for practical reasons, as opposed to a need to be insufferably moralizing. Sorkin said that the alternative would've been to just make up news, which he thought would feel far too unrealistic and would make the show "silly." It would also spare the series from having to bring the audience up to speed on everything it would be making up — not to mention, featuring literal fake news on a show about journalists just felt counterintuitive.

As Sorkin told The Telegraph in 2012, the show was "not meant to be a documentary" but rather a "romanticized, idealized newsroom." And in case you missed just how lofty the goals of his characters were, Sorkin made it pretty plain by having Will McAvoy identify with Don Quixote and analogize his hopes for the newsroom with Camelot — which pretty much dooms him and everyone else to failure. But it also reveals the exceptionally thin line between a valiant underdog and a self-righteous clown, which McAvoy struggles to recognize throughout the show's run.