Thomas Jane's The Mist Character Making Every Single Wrong Choice Was Entirely By Design [Exclusive]

Stephen King is one of the most prolific and efficient writers of our time, seemingly putting out new books at a pace faster than they print new editions of the New York Times. And when an author of King's stature puts out quality books at a speed that would make George R.R. Martin blush, movie adaptations are bound to come. Movies like "The Shining," "Misery," and "The Shawshank Redemption" all originated from novels by King, though their adaptations have gained ample acclaim in their own rights.

Among the most beloved of the films based on King's writing is "The Mist," a 2007 horror film directed by Frank Darabont, of "The Shawshank Redemption" and "The Walking Dead" fame. The film focuses on a group of ordinary people who become trapped in a grocery store when a mysterious mist envelops the whole town. The people then spend the movie grappling with their extraordinary circumstances and the horrible beasts that reside within the mist.

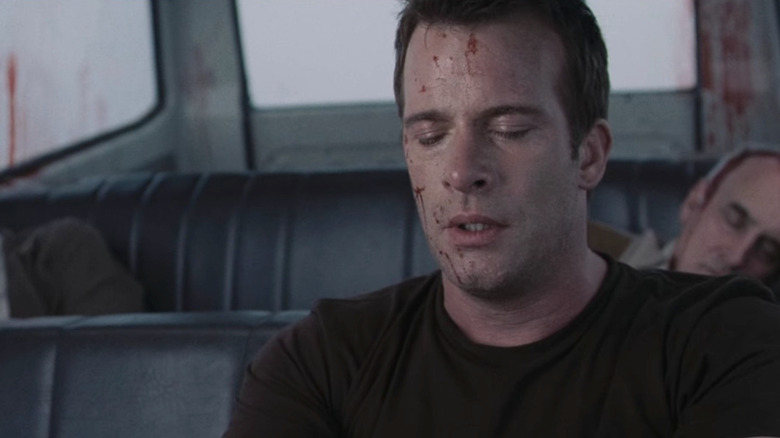

The movie's ensemble cast excels, creating an environment reminiscent of a more devastating "Lord of the Flies." The film's main character, portrayed by Thomas Jane, spends the movie protecting his 8-year-old son and attempting to navigate the increasingly tribalistic dynamic of the people trapped in the store. Jane's character is a classic everyman, an artist, and a father thrust into extremely strange circumstances, forced to act as a hero in a time of supernatural danger. What sets "The Mist" apart, however, is how often it seems to punch Jane's character right in the face, metaphorically speaking. Whereas other, similar, movies would have the hero doing the right thing and achieving success, Jane's character was more of a hapless Charlie Brown figure, with all of his decisions immediately coming back to bite him — a decision Darabont made intentionally.

Eroding morality

/Film now celebrates the 15th anniversary of "The Mist" with an oral history of the film by Eric Vespe, where we were able to hear from Frank Darabont himself about the fruitless nature of the film's protagonist's efforts. According to him, it was a choice he made to be provocative and run against the nature of a normal movie:

"When I was writing the script, I thought, this guy is making every right decision for every right reason, and every decision he makes turns into a disastrous choice and I thought, this is really interesting. This is really provocative because it runs counter to what we expect from a movie. In most movies. You see your hero, even if he's encountering obstacles or barriers or things kind of go bad, but ultimately they keep making the right decisions and it winds up with the right choices. This is the opposite. And I thought this is a radical departure from how most movies work and how most movie heroes work. In a sense, it is a mirror to reality because sometimes with our best intentions and our best actions, we get screwed anyway because the world is such a messed up place."

Darabont's filmography has seen him deal with issues of the effectiveness of morality before. While something like "The Shawshank Redemption" held a more optimistic view of human nature, "The Walking Dead" was an entire series predicated on the idea that, in extraordinary apocalyptic circumstances, traditional morality will be the first thing to go out the window. "The Mist," which he directed years before he took the helm of the AMC series' launch, acts as a pressurized version of the post-civilized setting of "The Walking Dead," with the enclosed setting of the grocery store only further exacerbating the deterioration of the people within.

Facing extremism

Even Frank Darabont admitted, in the oral history, that the change in tone between "The Shawshank Redemption" and "The Mist" was partially due to his personal dissent into cynicism. "What you had actually was an older filmmaker who was just a little more pissed off than the younger filmmaker who was so full of optimism and hope that he made 'Shawshank Redemption,'" said the director. "Now I'm just kind of a pissed-off older guy, and that's what I wanted to express."

"The Mist" came out in 2007, near the end of the George W. Bush administration. The Iraq War was at its deadliest point, and the president's approval ratings were dropping rapidly. As political polarization within the American public became more and more prominent, Darabont wrote "The Mist" partially as a criticism of what he saw as the increasing prominence of radical voices in society.

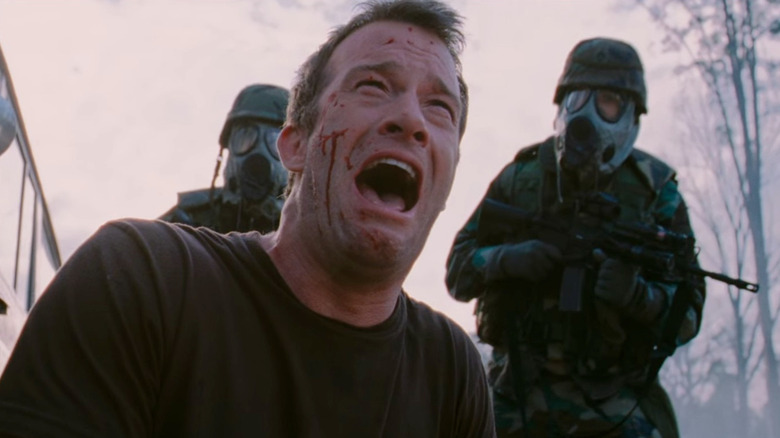

"Most of us are in this reasonable mass middle of things, but at the edges on both sides, you have this incredibly radicalized, extremist element that is driving the conversation, and it's no longer even a conversation. Now it's a shouting match. Now it's a duel to the death. The extremists are driving the bus and the rest of us have no choice but to ride along and scream in horror as things get more and more crazy and extreme and that was my everyman in that movie. That was David Drayton. That was the character Tom Jane played."

While Darabont's take is a bit too "both sides are equally bad" for my taste, it's no question that, in extreme circumstances, those who offer extreme solutions tend to end up in charge. These are the issues that Jane's character faces during the movie, a man trying to maintain reasonableness in an unreasonable scenario.

A harsh conclusion

Thomas Jane's character, David Drayton, spent the movie finding himself as the lone voice of reason among increasing amounts of mob mentality, violence, and panic. Whether it was him dealing with the increasingly violent religious sect that emerged among the survivors, who began sacrificing people to appease the monsters or the people who straight up refused to believe that anything had gone wrong, eventually walking willingly into the mist and meeting their doom. Drayton tries his best to act reasonably among such escalating foolishness, but at every turn, his decisions go wrong and cost people their lives.

This pattern of futility comes to a head during the movie's shocking and impactful ending sequence. The ending, which differs from the ending of Stephen King's original novel, features Drayton and a few others finally having escaped from the grocery store, finding shelter in a car. With only four bullets left in his gun, the group accepts their impending fates, and they decide to die by suicide rather than be victims of the horrors around them. As the fifth man with four bullets, Drayton kills the four other survivors, including his young son, and then awaits his fate. Not long after he makes this agonizing choice, the army arrives on the scene, and it appears the day has been saved, but not before he made an unnecessary sacrifice.

The divisive ending has been praised by King himself. It's the ultimate example of Drayton making what appears to be a noble choice, putting others out of his misery and sacrificing himself, only to have the rug swept from under him, realizing they were mere minutes away from rescue. It's a final gut punch that cements the theme of the fruitlessness of rationality in crisis.

Futile heroism

15 years later, Frank Darabont is still very proud of the choice he made with the movie's ending. To him, this final horrible twist of the knife was necessary to emphasize his message against what he saw as rising extremism in society, which he spoke about in the oral history:

"The movie worked as a warning shot, as a flare sent up from a concerned storyteller. And I love movies that do that. I love movies that can shake us up a little bit. So that dynamic of [David Drayton] making all the right decisions, but it's going to go in the sh***er was a very conscious thought in my head."

Whether or not you completely agree with Darabont's condemnation of political polarization, the fate of David Drayton can still resonate with anybody who's envisioned themselves being forced to make big decisions in a crisis. Most of us would like to believe that, like Drayton, we would keep our heads about us and make morally correct choices in these apocalyptic scenarios. We want to think that we could muster up the courage required to do what Drayton does. What Darabont argues is not that people aren't capable of maintaining their morals in these scenarios, but that even when someone does so, there's still a massive likelihood that everything goes wrong regardless of your choices. Even those that can act like individual heroes are still victims of the tidal whims of the masses and the cruel randomness of tragedy.