Why Studio Ghibli Has Lost So Many Incredible Filmmakers

There was once a man named Mamoru Hosada who decided to become an anime director. After a phenomenal career at Toei, where he worked on classic episodes of "Digimon" and "Revolutionary Girl Utena," he was recruited by Studio Ghibli to direct their upcoming film "Howl's Moving Castle." Unfortunately, Hosada's project was cursed from the beginning. Much of Ghibli was already busy crafting "Spirited Away." Hosada worked hard to secure a team of animators, but he could only do so much by himself. The harder he worked to keep "Howl's Moving Castle" alive, the faster it became a time and money sink. Sooner or later, the film collapsed, and Hosada was removed from the project. In an interview with Animestyle, Hosada expressed his feelings of guilt for the animators he was forced to abandon. "I had lied to them," he said. "I had betrayed them. Now nobody would trust me again."

Hosada would take all his confusion, sorrow and rage and put it into a "One Piece" movie. In "Baron Omatsuri and the Secret Island," the pirate Luffy and his crew travel to an island of games run by a mysterious Baron. The Baron is jealous of Luffy's friends, and uses powerful magic to divide and conquer them. At the end of the film, after the most harrowing scene in "One Piece" history, the audience is taught the difference between Luffy and Baron Omatsuri. Luffy is able to make new friends after being separated from his old ones. But the Baron cannot move on from the friends he lost long ago, and so he is doomed to be forgotten. "Baron Omatsuri" has never been made officially available in the United States, and yet its story has been told again and again. It is one of the great anime ghost stories.

Our war game

Mamoru Hosada's bad experience at Ghibli may be infamous, but it was not unique. The director Sunao Katabuchi similarly struggled at Ghibli. According to a recent piece by Animation Obsessive, Katabuchi was chosen to direct "Kiki's Delivery Service" after proving himself in the trenches to studio heads Hayao Miyazaki and Isao Takahata. Just like what would happen later with "Howl," the film became increasingly ambitious and expensive in a way that made producers uncomfortable. "Investors weren't interested," says Animation Obsessive, "unless Miyazaki directed [the film] himself." Katabuchi was demoted to assistant director, and Miyazaki took the lead. The resulting film was excellent, but Katabuchi was frustrated at how his chance to prove himself had slipped through his fingers. When Katabuchi was finally given the opportunity to direct his first film, "Princess Arete," it was at Studio 4C rather than Studio Ghibli.

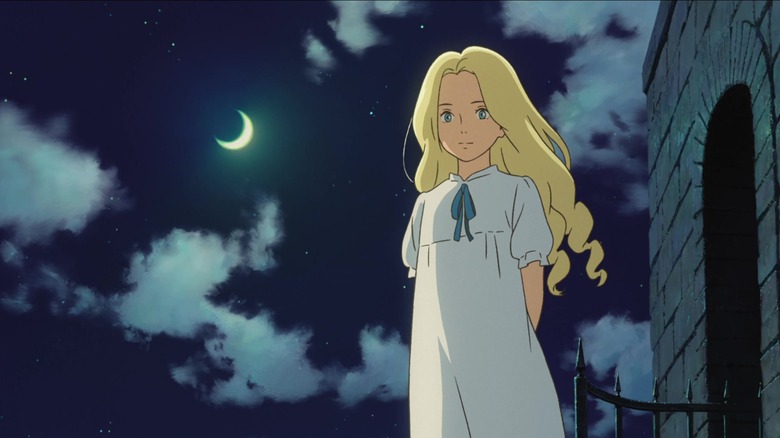

Hiromasa Yonebayashi's time at Ghibli was far more positive but uniquely frustrating in its own way. In his time there he directed two films, "The Secret World of Arietty" and "When Marnie Was There." "Marnie" especially saw Yonebayashi come into his own. "With Marnie," he would say to Little White Lies, "what I was conscious of was purely the enjoyment of the audience." But the studio's output was slowing down; Miyazaki had (briefly) retired after 2013's "The Wind Rises," and Takahata was busy with his final film "The Tale of Princess Kaguya." Yonebayashi, who longed to make the kinds of Ghibli films he grew up watching, realized that he could no longer fulfill his ambitions at the studio. So he quit Ghibli after directing "Marnie" in 2014 and founded Studio Ponoc with producer Yoshiaki Nishimura.

Ghibli children

Why would anybody want to leave Studio Ghibli? The studio founded by Hayao Miyazaki and Isao Takahata is one of the most beloved in Japan. Miyazaki and Takahata founded the studio with producer Toshio Suzuki to make the original anime films they wanted to see. Years of toiling in the TV anime industry had taught them that the demands of television were incompatible with the quality they wanted. As former labor organizers, Miyazaki and Takahata fought to create a work environment where the work of artists was respected. They sought to hire and train in-house staff rather than relying on underpaid freelancers. Ghibli's films were extraordinarily difficult and time-consuming to make; late in production, the best intentions of the founders were thrown out the window. But the studio earned its reputation as a place where talented artists were given the time and money to create lasting work at a scale incomprehensible elsewhere.

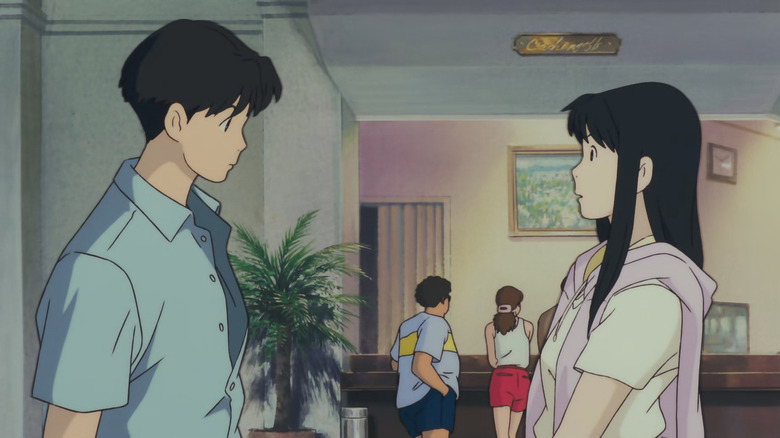

It should also be said that the producers at Ghibli were well aware that they needed directors other than Miyazaki and Takahata for the studio to survive. Talented directors like Mamoru Hosada were hired from outside the studio with the hope that they might one day become a box office draw like Miyazaki. Another director, the talented Tomomi Mochizuki, was scouted to direct the TV film "Ocean Waves" In 1993. "Ocean Waves" was intended as a training project for young Ghibli animators to learn on the job in a less intensive environment. Later, 1995 saw the release of "Whisper of the Heart," the directorial debut of longtime Ghibli associate Yoshifumi Kondo. Miyazaki and Takahata hoped for Kondo to be their successor, taking the studio into the future.

Summer wars

Unfortunately, taking the reins of Ghibli proved to be a near-impossible task. Mochizuki was hospitalized in the process of directing "Ocean Waves." Kondo died of an aneurysm in 1998, just three years after the release of "Whisper of the Heart." Producer Toshio Suzuki would claim in his biography that Kondo was overworked by Isao Takahata, whose films and past television productions were notoriously demanding. Other ex-Ghibli folk later spoke of the challenges posed by Ghibli's unique culture. Former Ghibli producer Hirokatsu Kihara said in an interview with Dazed that "there's a sense that everyone is replaceable ... rather than hire creatives with great ideas, they will hire people who will please the producers." These stories may very well be true, although you should always take the word of powerful anime executives with a grain of salt.

Speaking personally, I believe that the greatest challenge Studio Ghibli faces today is Hayao Miyazaki himself. Miyazaki is a once-in-a-generation artist able to produce better drawings faster than his peers. While working on Takahata's TV project "Heidi, Girl of the Alps," he created the "layout" process that refined storyboards into detailed frames. This provided a great reference for the animators, decreased the number of retakes and swiftly became the standard for the TV anime industry. But Miyazaki was only able to do this because of his skill and speed. He's also a terminal workaholic who lives to draw. Despite his age, he has proven exceptionally difficult to replace.

Unfulfilled animators

Kihara said an interview with Nanjinsan that "every single frame" in a Miyazaki-directed Ghibli film "has Hayao Miyazaki's detailed input." This resulted in high-quality output, but has also served as a creative limitation. Miyazaki has a reputation for redrawing every single frame that passes through his hands to his own exacting specifications. Only a handful of artists have been spared Miyazaki's pen. Of course, corrections are an essential part of the production process. That Ghibli has such a rigorous standard of quality is a point in its favor. But Miyazaki's tendencies towards micromanagement are also uniquely frustrating for a studio as driven by artists as Ghibli. Animators have their own preferences and don't always take kindly to being subsumed by Miyazaki's style.

One such example is Masashi Ando, one of the most famous animators to pass through Studio Ghibli. Ando handled character design alongside Yoshifumi Kondo on "Princess Mononoke," and served as both character designer and animation director on "Spirited Away." But according to Sakuga Blog, he was driven by his "pursuit of realism in animation" to argue with Miyazaki and eventually leave the studio. He then joined forces with Satoshi Kon, and contributed to Kon's television series "Paranoia Agent" and last film "Paprika" before the director's untimely death in 2010. Artists like Ando are tough to replace. Similarly, a studio like Ghibli offered opportunities to Ando that would be hard to find anywhere else. But Ando decided that in order to do the kind of work he preferred, he had to move on.

The witch who gave up on being a witch

The greatest challenge faced by Miyazaki's successors, then, is that they were not Miyazaki. Mamoru Hosada and Sunao Katabuchi were never offered the support they needed to thrive at Ghibli. They could only find their full potential elsewhere, where they had the freedom to make films their own way. Miyazaki's influence so thoroughly permeates Ghibli that even Takahata was affected. He was a good friend of Miyazaki to the end and is considered by some to be Ghilbi's true master. But Miyazaki's films remain more popular abroad. Ghibli merchandise is dominated by "My Neighbor Totoro" and "Kiki's Delivery Service," rather than "Only Yesterday" or "Pom Poko." Not to mention that "Spirited Away" was the first anime film to win an Oscar in 2003, while Takahata's magisterial "Tale of Princess Kaguya" lost to "Big Hero 6" in 2014.

Hayao Miyazaki is a finite resource. "How Do You Live" may be his final film, unless his work ethic ensures even his skeleton continues to animate after his death. Producer Toshio Suzuki has pulled every trick in the book to obscure Miyazaki's decreasing presence in the studio's output. Says Jonathathan Clements, later Ghibli films obscure "the precise details of who did what with an entirely alphabetical crew listing, so that when other directors took the reins, only the attentive audience members would even notice." "The Secret World of Arietty" was directed by Hiromasa Yonebayashi, and yet those not paying attention might see Miyazaki's name (as scriptwriter) and imagine the film was his. It's no wonder, then, that Yonebayashi left.

The future

At the moment, the best place to see the work of ex-Ghibli talent is in their own productions. In 2016, Sunao Katabuchi directed "In This Corner of the World," an obsessively detailed recreation of Japan's home front during World War II that rivals Isao Takahata's brutal "Grave of the Fireflies." Yonebayashi directed the Ghibli-esque "Mary and the Witch's Flower" at Studio Ponoc in 2017, and later contributed a segment to the anthology "Modest Heroes" in 2018. Masashi Ando brought real firepower to Makoto Shinkai's 2016 blockbuster "your name," punching up Shinkai's trademark sentimentality with genuine character acting. Just last year, Ando co-directed his first film, "The Deer King."

Mamoru Hosada has become a successful director at Studio Chizu. He continues to make films unabashedly inspired by his own life; both "Wolf Children" and "Mirai" riff on his experiences as a parent. Last year's "Belle" combines the technology of "Summer Wars" with "Beauty and the Beast." A pedant might argue that his modern productions lack the youthful exuberance of his early television work. Certainly, his recent films lack the raw anger of "Baron Omatsuri and the Secret Island." But I can't begrudge Hosada the opportunity to make the movies he wants, even if he's changed as an artist over the years.

My personal favorite Hosada film remains "The Girl Who Leapt Through Time." Its production saw Hosada at a crossroads, deciding once and for all if he could make it in the industry as a film director. Studio Ghibli stands at that crossroads today. Will the studio continue to pursue the ideals of Miyazaki and Takahata? Or will it become something else? Just as so many incredible filmmakers came into their own after leaving Ghibli, perhaps Ghibli itself might one day surprise us.