High Noon Saved Gary Cooper From A Sea Of 'Crappy Scripts'

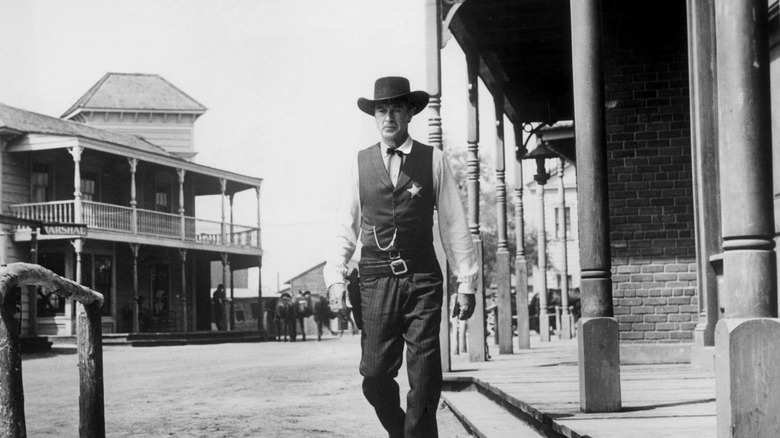

So much classic Western iconography comes directly from the images of Fred Zinneman's 1952 film "High Noon." The ticking clocks awaiting the arrival of a dangerous train, the lone figures in a dusty town square, and Gary Cooper's sweaty, sickly close-ups are unforgettable. His desperate, acclaimed performance in the movie effectively resurrected a floundering career.

His appeal, one of ordinary heroism, was frequently wasted on movies that didn't know how to use him. Like many actors whose rise to fame preceded World War II, he struggled with changing audience expectations – there was little room anymore for the optimism of Frank Capra's "Mr. Deeds Goes to Town" or the tough patriotism of Howard Hawks' "Sergeant York," the latter of which proved enormously influential for Clint Eastwood.

He was in high-profile flops like the Ayn Rand-scripted 1949 adaptation of her own novel "The Fountainhead," an ultimately dramatically inert film that demonstrated his limitations. Cooper's national reputation wasn't helped by his affair with his "Fountainhead" co-star Patricia Neal, which led to "turmoil for all involved," per Mary Claire Kendall.

All of this contributed to his starring in "High Noon," the iconic clock-ticking Western about a man trying to do good in a selfish world. The movie was not meant to be a hit, and it certainly wasn't meant to be a classic. With a budget under $1 million, it was a lucky confluence of events that it was anywhere near as successful as it was. And Gary Cooper wasn't even the producer's first choice for the lead.

An un-American script

In fact, Cooper wasn't even in their top 10. "High Noon" producer Stanley Kramer was hoping for Marlon Brando, Kirk Douglas, a bigger, more fashionable name than Cooper to sell this urgent story, per Vanity Fair.

Kramer and writer Carl Foreman had come up together in Hollywood, capitalizing on the post-war hunger for movies dealing explicitly with the national mood. Kramer made multiple movies with this directive in mind, like 1949's "Home of the Brave," a saga of racism in the military. His profile in the industry grew because of his financially efficient producing sense and vision, buoyed by Foreman's screenwriting. "High Noon" proved their talent.

For a producer-writer team familiar with the thorny contours of modern life, a Western could demonstrate its versatility. And it wouldn't be escapist fare – it would be a movie that dealt obliquely with the McCarthyist anti-Communist witch hunts overrunning society (and Hollywood) in the late '40s and early '50s. Its target was the famous Hollywood blacklist that exiled artists with any history of Communist leanings from the industry.

One of the men who led the Hollywood blacklist was perhaps the most famous Western star of all time: Gary Cooper's good friend John Wayne. He found "High Noon" deplorable. Years of serving as President of the Motion Picture Alliance had given him a keen eye for subversive Communist subtext in movies, and "High Noon" seemed to have more than a bit. As he told Playboy in 1974, the script was "the most un-American thing I've ever seen in my whole life."

Gary Cooper was a bargain

Per Vanity Fair, Cooper's daughter Maria Cooper Janis claimed producers "would send him these crappy scripts and at some point you have to do one of them." "High Noon" was no "crappy script," even if John Wayne felt the need to respond to it with "Rio Bravo."

The big stars of the day balked at the paycheck, but Cooper's mediocre run of movies and weakened reputation let him follow his taste. He loved the script.

Carl Foreman's screenplay took the ingredients of a Western – vengeance, violence, and the demands of the law – and streamlined them into an 80-minute suspense piece. It tells the story of Marshal Will Kane (Gary Cooper), on the brink of leaving the small town of Hadleyville with his young Quaker wife (Grace Kelly). In the morning, he receives word that the vicious killer (Ian MacDonald) he put away years ago is en route. The killer will be in town by noon.

Nobody in town offers to help Will. They ask him if he can reward them, or they skip town themselves. He's left alone to deal with the violence and to stand up for himself. Foreman's script dealt with his own feelings as an artist continually summoned in front of HUAC to be a "friendly witness."

Foreman found Cooper to be a "relic" of the studio system, per Vanity Fair. They got him for $100,000, a huge chunk of the budget, but a steal for an actor of Cooper's repute. If he came off old and unwieldy next to Grace Kelly, that was what they had paid for.

Cooper's commitment

During the filming of "High Noon," Carl Foreman was subpoenaed to a HUAC hearing one last time, and continued to be unsupported. Vanity Fair claims producer Stanley Kramer cut ties with the writer permanently as he worked to complete the movie and avoid the stink of Communist accusations. After filming, Foreman moved overseas, a fact John Wayne took credit for in a 1974 Playboy interview.

Gary Cooper was conservative like Wayne, and had many friends in the Motion Picture Alliance. The accusations swirling around Foreman could have been destructive for his career. But he saw the value in the movie, even as Kramer criticized his performance. The producer wrote of Cooper in his memoirs that he "seemed not to be acting but simply being himself." That turned out to be what gave the movie its soul, the immortality that turns movies into Broadway plays 70 years later.

Cooper was undeniable, no longer the stock figure he had become in his late '40s movies. Even with the stomach ulcers from which he suffered according to Larry Swindell's "Gary Cooper," his performance is wonderful, understated, complex. Others took notice as well – he won the Oscar for Best Actor and saw his reputation fully turn around. Because he was in Europe during the award's presentation, he had to send an emissary to pick it up when his name was called. Per TCM, that ended up being John Wayne, who claimed he would call his agent and find out why he "didn't get 'High Noon'" instead of Cooper.