The 15 Best Films Of The 1920s

A few decades after the first experiments with the new technology of film, cinema in the 1920s was beginning to come of age. Filmmakers mastered the essentials and embarked on ambitious storytelling projects with increased flair and sophistication, turning movies from novelty to art in just a few short years. The film industry began operating at full capacity in the 1920s, churning out feature-length productions on a scale and frequency that would have been unthinkable a decade earlier.

Filmmakers of the 1920s start to diversify, some becoming experts in the large-scale epics that were the earliest versions of blockbusters, while others honed a unique style as auteurs that would define the period as part of a larger artistic movement. Our first movie stars come from this era, both silent comedians whose death-defying pratfalls rival any stunts performed today as well as romantic matinee idols who had audiences eating out of the palm of their hands. A lot of film fans — even those who appreciate the history of cinema — tend to neglect the 1920s, a decade almost entirely pre-talkies. Still, silent cinema has a great deal to offer, not just in terms of the influence it had on later films, but as enjoyable entertainment in its own right.

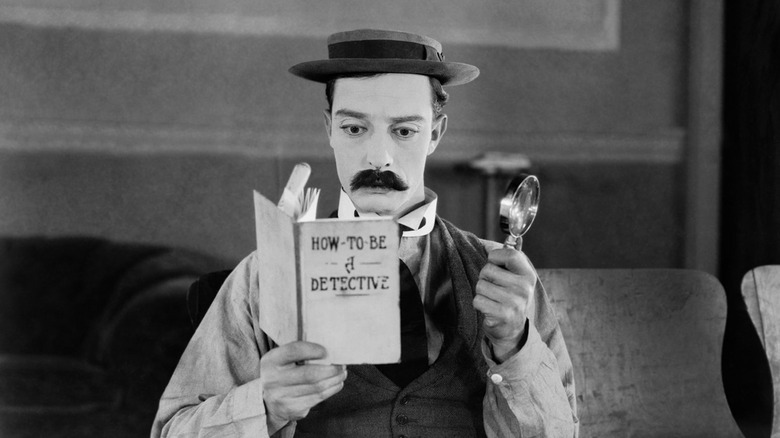

Sherlock Jr. (1924)

"Sherlock Jr." may not be one of Buster Keaton's most visually ambitious films, running at a tight 45 minutes long and lacking some of the over-the-top set pieces that we see in movies like "The General" or "Neighbors." However, he rarely plays with the concept of filmmaking and storytelling as much as he does here. Keaton stars as a shy projectionist who fantasizes about becoming a famous detective, and we witness his daydreams of confidently solving a crime as he loses focus at work.

Perhaps the most memorable sequence is when he finds himself stuck in a movie theater screen, subject to the whims of the film's cuts: He's sitting on a peaceful garden bench one moment, falling into a crowded city street the next. His playfulness in using this fantasy sequence as a springboard for some of his famous pratfalls is expertly conceived, and the warmth that radiates throughout the entire film makes "Sherlock Jr." a favorite among Keaton fans.

My Best Girl (1927)

There were plenty of romances throughout the silent era, along with plenty of comedies (largely from Charlie Chaplin, Buster Keaton, and Harold Lloyd) that have a romantic element. Yet few films feel as much like a precursor to the modern rom-com as "My Best Girl," starring America's Sweetheart (despite being a Canadian citizen) Mary Pickford and Charles "Buddy" Rogers, who would become her third and final husband after a high-profile divorce from swashbuckling matinee idol Douglas Fairbanks.

Rogers plays Joe Grant, the son of a department store owner who attempts to avoid accusations of nepotism by not telling anyone who his father is. Pickford's poor stockgirl Maggie falls in love with him, not realizing his true identity and that he happens to already have a fiancé. Against all odds, sparks fly and the chemistry between these two lovebirds is undeniable. Both Pickford and Rogers have an irrepressible charm, and they are well-matched in this sweet and good-natured romantic comedy.

The Man Who Laughs (1928)

If you've ever watched a Batman movie that features the disturbingly broad grin of the Joker, you owe a debt of gratitude to "The Man Who Laughs." Framed like a horror movie but given a sense of tragedy by the emotive performance of Conrad Veidt, "The Man Who Laughs" tells the story of an orphaned boy who is purposefully disfigured as an act of vengeance against his aristocratic father. Thanks to the efforts of primitive surgeons, his face is now contorted into an unsettling permanent grin, making him an object of mockery wherever he goes.

Although he is caught up in court intrigues as an adult, he renounces his claim to the nobility — which is only accompanied by ridicule — in favor of a quiet life with people who love him for who he is. "The Man Who Laughs" has found a devoted audience over the years, with Bob Baker of Time Out referring to it as "one of the most exhilarating of late silent cinema," and reserving specific praise for Conrad Veidt's expressive turn in the lead role.

The Adventures of Prince Achmed (1926)

It's difficult to find words to express how in awe we are of director Lotte Reiniger's work in "The Adventures of Prince Achmed." Not only does she craft a moving, coherent adaptation of "One Thousand and One Nights," but she does so using silhouette animation. This is a painstaking process of manipulating cardboard cutouts of each of the characters and set pieces so that they would appear to be in motion, almost as though they were shadow puppets. The amount of work involved is staggering.

As you notice her attention to detail and the delicate lines of each figure as they move gracefully throughout the film, the scope of this project becomes overwhelming. "The Adventures of Prince Achmed" is the earliest surviving feature-length animated film, showing the full extent of what the medium is capable of given the creative ambition and technical skill of the animator. Eat your heart out, Walt Disney.

The Ancient Law (1923)

Did you ever want to watch "The Jazz Singer," but without all the problematic blackface? That's basically what you get with "The Ancient Law," minus a few musical numbers. "The Ancient Law" tells the story of Baruch, a Jewish boy from the shtetl whose passion for theater brings him in direct conflict with his rabbi father, who expects holier things of him. Discovering a genuine talent for acting, he runs away from home and joins a theater company but continues to battle antisemitism at every turn. His religious background makes it more difficult for him to achieve success at the highest level.

At a certain point, Baruch must make a choice between staying true to himself and his heritage or abandoning his background and systematically removing everything that makes him identifiably Jewish. Ultimately, his happiness depends upon finding a way to reconcile the two. Director E.A. Dupont expertly builds two distinct worlds in "The Ancient Law": the warm but suffocating shtetl and the cold elegance of 1860s Vienna, creating a lush exploration of culture and religion.

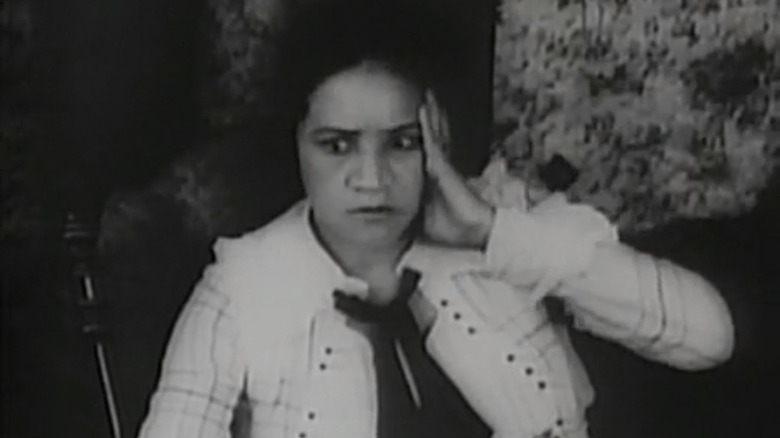

Within Our Gates (1920)

"Within Our Gates" occupies an extremely significant position in film history as the earliest surviving film made by a Black director, Oscar Micheaux. His work not only showcases a voice that hadn't been heard in cinema before but reflects an entire community of middle-class Black Americans who didn't see anything approaching their actual lived experiences onscreen until this point.

"Within Our Gates" features the journey of a young Black woman who travels to the North to raise funds for a school to serve children in her local community. Released the year after "Birth of a Nation," "Within Our Gates" operates as a stern refutation of the former film's depiction of racial violence, with a brutal flashback sequence detailing the murder of Sylvia's family by marauding white men, the same characters who would likely be hailed as heroes in D.W. Griffith's controversial film. Micheaux would go on to make more than 40 movies after this one.

Girl Shy (1924)

Harold Lloyd doesn't always get the credit he deserves as a silent film comedian, frequently overshadowed by other towering giants of the genre like Charlie Chaplin and Buster Keaton. He's in his element with "Girl Shy," a sweet comedy with a moony romantic angle that was tailor-made for him. A tailor's apprentice who longs for the career of a successful author, Harold attempts (with hilarious incompetence) to write a how-to book about seducing women, a proto-pickup artist of the Roaring Twenties.

His budding relationship with Mary Buckingham (Jobyna Ralston) is warm and appealing (they worked together on four more films over the next few years, their on-screen chemistry now proven), even as it is perpetually interrupted by the wild comedic set pieces that were a prerequisite of the genre. Even with these moments of silliness, "Girl Shy" stands out in comparison to Lloyd's earlier work in that it is much more focused on its characters than its shenanigans.

A Page of Madness (1926)

Although American and European films occupy the most space in cinematic history textbooks, even in the 1920s there were already thriving film industries in Asia and other parts of the world. Japan in particular was developing rapidly, as evinced by Teinosuke Kinugasa's "A Page of Madness." An avant-garde film from the Shinkankakuha school, it tells the story of a man who takes on a job as a janitor at a psychiatric institution as a means of atonement towards his wife, who is a patient there. As stressors related to work and family flare up, he begins to experience a series of dreams and fantasies that blur the lines of reality in his mind.

Startlingly eerie in its visual compositions, "A Page of Madness" has earned critical acclaim after being considered lost for nearly 50 years. BBC Nottingham referred to it as "a balletic musing on our subconscious nightmares, examining dream states in a way that is both beautiful and highly disturbing," while Time Out called it "one of the most radical and challenging Japanese movies ever seen."

The Phantom Carriage (1921)

Revolving around an eerie New Year's Eve ghost story, Victor Sjöström's "The Phantom Carriage" uses technical innovation and superb production design to build an intensely atmospheric experience. The legend of the phantom carriage, as we learn from one character early in the film, is that it is Death itself traveling across the world to collect souls who have died. He warns that one must be careful not to die on New Year's Eve, for if you are the last person to die before the clock strikes midnight you will be given the burden of driving the carriage and taking recently departed spirits to the afterlife for one entire year.

Both visually and emotionally complex, "The Phantom Carriage" was a major influence on many directors of the mid-20th century, including Ingmar Bergman, who said of the film, "It completely overwhelmed me. I was shaken to the core." Stanley Kubrick also paid homage to it with his famous axe scene in "The Shining."

Un Chien Andalou (1929)

If you think they didn't have films that felt like dropping acid all the way back in the 1920s, guess again! "Un Chien Andalou" is an experimental short film with deep roots in the surrealist art movement. It was a collaboration between Luis Buñuel and Salvador Dalí, so that should probably tell you everything you need to know. There's not so much a plot to "Un Chien Andalou" as there are themes and visual metaphors. The entire production plays out like a journey through the subconscious, with images blurring together and rapidly being distorted into something else.

From a technical perspective, it masters the art of the match shot, where a series of images are put together so that our mind infers an action. In this case, it results in the iconic image of a man holding a razor up to a woman's eye, followed by a thin line of clouds cutting across the moon, followed by a dead cow's eye being sliced open, creating a horrifying visual that is perhaps this film's most enduring element.

The Kid (1921)

One of the aspects of Charlie Chaplin that made him such an enduring figure in silent film is the sentimental streak that runs a mile wide throughout all of his comedy. The laughs in his films can't exist without at least a little bit of melancholy. This is especially true of "The Kid," a movie that features Chaplin as the Tramp becoming an unlikely father figure when a baby boy is abandoned by his mother (who quickly changes her mind, but to no avail) and inadvertently falls under the Tramp's protection.

As the infant grows into a child, their bond grows and the two couldn't be closer ... until the authorities discover that the Tramp isn't actually his father. They take the boy away in a heartbreaking scene that showcases how great an actor Chaplin really was. With the astonishingly emotive child star Jackie Coogan in the lead role, "The Kid" isn't Chaplin's funniest movie, but it's without a doubt one of his most moving.

The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920)

For horror enthusiasts, "The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari" is a must-see. A German expressionist film borne out of the anxiety and disillusionment of the First World War, it's filled with sharp angles and distorted imagery of its cityscape. Our hero Francis must protect the woman he loves from the machinations of the evil Dr. Caligari and his sleepwalking henchman Cesare (played by Conrad Veidt at the beginning of his long career).

Not everything is quite as it seems: "The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari" asks us to question not just the authority of institutions (Dr. Caligari is the head of a psychiatric hospital), but whether or not we can trust our own perceptions of reality itself. Often credited as having the very first twist ending in cinematic history, it went on to have a massive impact on the entire horror genre. Its influence is seen everywhere, from the wave of dark German films that would come in its wake to the gothic storytelling of Tim Burton.

Metropolis (1927)

There are a few films that come out every decade that are just no-brainers when it comes to "Best Of" lists, and "Metropolis" is one of them for the 1920s. In it, there is a wealthy class of people who live in a glittering urban utopia, all while an underclass of workers slaves away to maintain it while forced to endure inhumane conditions. The politics of "Metropolis" should be fairly clear by this point.

The sheer ambition that Fritz Lang displays over the course of the film is enough to earn it a vaunted position in film history. It features tremendously intricate sets that turn a factory into an entire cityscape, as well as a postmodern temple for the gods of technology and progress who demand human sacrifice. All of this is seemingly unbound by anything other than Lang's imagination. Its ghoulish imagery of factory workers marching into work, their slumped bodies operating completely in unison, is more unsettling than anything modern horror has to offer.

The Big Parade (1925)

"The Big Parade" was released just seven years after the end of World War I, when audiences didn't particularly need to be told that war was hell (they had all just lived through it). Directed by King Vidor and starring John Gilbert, "The Big Parade" nevertheless offers up one of the best anti-war films in cinematic history. Gilbert plays Jim Apperson, a wealthy, entitled young man who decides to enlist when war breaks out thinking that it will be an adventure.

When he is shipped off to France, he quickly learns about the horrors of combat, as the film shows him marching through eerily desolate forests, waiting for bombs and artillery fire to fall on him and his brothers-in-arms. Gilbert, often unfairly maligned as his career fell apart once Hollywood was on the cusp of the sound era, puts in a powerful performance alongside Renee Adoree, who plays his French love interest.

Sunrise (1927)

A man and a woman live a quiet life in the countryside, and they are happy together ... until a siren from the city comes calling, tempting the man with all the exciting things he could have if he ditched his wife and took up with her in an urban paradise of seemingly endless possibilities. This is the story of "Sunrise," a silent drama from F.W. Murnau in his Hollywood directorial debut.

Despite being nearly 100 years old, the film's legacy is assured. Not only is it widely regarded to be one of the most significant pieces of early cinema, but it also has the honor of being one of two films to be awarded the equivalent of the best picture Oscar at the very first Academy Awards. Back then, the category was divided into the best unique and artistic picture, and outstanding picture, the latter of which was won by "Wings."