The Success Of Tim Burton's Batman Sparked A Legal Battle At Warner Bros.

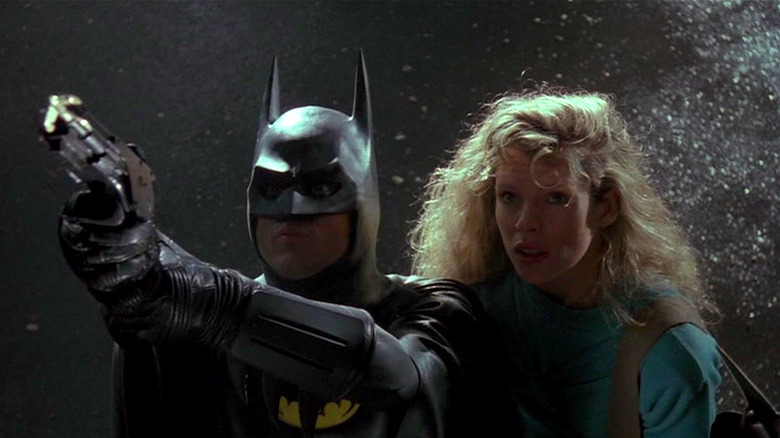

Many directors have taken on the challenge of bringing Batman to the big screen. Some have been successful, while others have created ... well, less successful renderings of the infamous vigilante. Tim Burton's 1989 adaptation of the comics is often looked upon as one of the best realizations of the story of Bruce Wayne. A charismatic Michael Keaton dons the cowl in Burton's vision, and he is largely convincing as he protects Gotham from the evil clutches of Jack Nicholson's maniacal Joker.

When the film was released, it was a huge success. Everything about the movie, from its fantastic casting to its score by Danny Elfman, helped make it a hit. It went on to break blockbuster records with a massive $40 million opening weekend, and went on to make $400 million in its initial run. Beneath the film's box office numbers, however, a darker tale of betrayal was unfolding. Oftentimes, when you have a hit on your hands, legal battles aren't far behind. And in the case of Burton's "Batman," the film's success sparked brawls that even the Bat's own batarang couldn't slice through.

Dynamic duos

To understand the legal issues surrounding Tim Burton's "Batman," you have to understand the complex relationship between two of Hollywood's most controversial men: Peter Guber and Jon Peters. Together, the duo made movie history by producing some of Hollywood's biggest projects. Prior to working on "Batman," Guber and Peters had been executive producers of other hits such as the Oscar award-winning "Rain Man," Steven Spielberg's "The Color Purple," and Adrian Lyne's "Flashdance." In recent years, Peters was also immortalized in Paul Thomas Anderson's "Licorice Pizza," where Bradley Cooper perfectly captures Peters' high-strung personality and obsession with his past love affair with Barbara Streisand.

The duo are controversial in "the biz" for a slew of reasons and allegations (Peters is one of the men in Hollywood who has come under fire for allegedly engaging in sexual harassment), and their climbs up the business ladder are painfully detailed in Nancy Griffin and Kim Masters tell-all book, "Hit & Run." The book outlines Peters' and Guber's journey to becoming two of the most successful studio executives in Hollywood, though their ascent to the top has not always been smooth sailing.

In one particular chapter of "Hit & Run," Griffin and Masters explain how two men — Benjamin Melniker and Michael E. Uslan, who owned the film rights to the "Batman" franchise and who were trying to get their script picked up — attracted the interest of Guber. Guber's merged company, Casablanca Record and Filmworks, struck a deal with them to make the film. What followed, however, was a complex series of hoops to jump through that ultimately, despite (or in spite of) the film's success, ended in legal pursuit.

In the shadow of the bat

According to Benjamin Melniker and Michael Uslan, their original contract with Casablanca Record and Filmworks guaranteed them "40 percent of whatever profit [Peter] Guber and [Jon] Peters received. It also stated that they 'shall be accorded credit as the producers of the pictures.'"

Guber and Peters, however, did not keep the two in the loop when developing "Batman" with Warner Bros. Because of this, Melniker and Uslan "assumed that the terms of the original deal [at Casablanca] would still apply."

That's not how things shook out. By the time Melniker and Uslan learned that "Batman" was set to go into production, it was too late. They tried to hang onto the legality of their original Casablanca contract, but they were told by Casablanca Record and Filmworks' head of business affairs that "if they did not sign an amended contract, they would be thrown off the picture entirely." The new contract was far less generous, giving "them nominal credit as executive producers, stripp[ing] them of creative involvement and consulting rights, and grant[ing] them 13 percent of net profits." When the film ultimately went on to be a blockbuster smash, Melniker and Uslan were obviously upset.

Melniker and Ulsan eventually "filed a breach-of-contract suit [...] in which they claimed to be 'the victims of a sinister campaign of fraud and coercion.'" where they lost out on having creative input on the film as well as reaping any of the movie's financial success (they each only ever earned $300,000 a piece). Nothing ever came of the suit — a judge threw the case out — and Melniker and Uslan are left to lurk in the shadow of the Bat they helped bring to life.