How A Nightmare On Elm Street Inspired A Whole Genre Of 'Rubber Reality' Horror Films

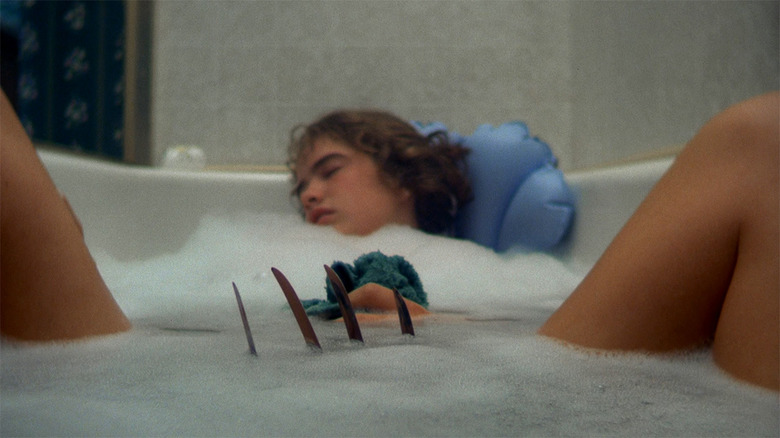

"A Nightmare on Elm Street" was the little movie that could, a film that became a turning point for its writer and director, Wes Craven. Inspired by a series of newspaper articles concerning a group of people complaining of having bad nightmares and then dying of mysterious causes soon afterward, the tale of dream demon Freddy Krueger (Robert Englund) menacing a group of teens led by Nancy Thompson (Heather Langenkamp) made such an enormous amount of money (as did its first few subsequent sequels) that it made distribution house New Line Cinema into "the house that Freddy built," and began a franchise that remains popular to this day.

Yet "Nightmare" wasn't only successful for its makers; it also added to the culture in numerous ways. It became a watershed moment for the horror film, providing a brand new template for unscrupulous producers and ambitious young stalwarts to follow ever since the prior blueprint of 1978's "Halloween" had begun to be used up by the mid-'80s. As befitting the erudite Craven, "Nightmare" was heavily inspired by classic arthouse and foreign films, meaning the rip-offs, also-rans and singular triumphs that followed had to do more than just come up with brilliant new ways of killing teenagers — they had to have some surrealistic imagination, too, lending the immediate wave of "rubber reality" horror films an artistic pedigree almost by default.

Craven does Cocteau

Wes Craven was inspired by his relatively-late-in-life deep dive into cinema history when he began to make films of his own, taking inspiration from Ingmar Bergman for "The Last House on the Left" and F.W. Murnau for "The Hills Have Eyes." When he was creating "A Nightmare on Elm Street," Craven sought to recapture the spooky surrealism on display in Jean Cocteau's 1946 adaptation of "Beauty and the Beast." The filmmaker was taken by Cocteau's surrealism, describing it as "a sort of outlaw form of looking at the world as semi-mad."

Thus, "A Nightmare on Elm Street" makes sure to make its world as mad as possible, featuring elements like a stairway that melts into goop, arms that stretch out impossibly wide, and lines between the dreaming and waking world that become blurred in increasingly upsetting ways.

In essence, "Nightmare" removes the safety of reality for the characters and the audience while allowing the filmmaker a fair amount of artistic freedom; in a way, anything goes.

The birth of 'rubber reality'

Surrealism in the horror film was certainly nothing new by the time Freddy graced cinema screens. An early example is Carl Theodor Dreyer's 1932 film "Vampyr," which introduced dreamlike imagery and structure to a vampire tale. Other movies over the ensuing decades used surrealism to heighten the terror of their stories, from Roman Polanski's "Repulsion" to Nicolas Roeg's "Don't Look Now."

What Craven did with "Nightmare" was introduce surrealism into the "dead teenager" structure that had become so prevalent with the rise of the slasher film, providing a clear path for other filmmakers to follow without them needing to go too arthouse. Speaking in 1986 at a Fangoria Weekend of Horrors convention, Craven observed the influence of "Nightmare" on the latest wave of horror films:

"The interesting thing that's happening now, I think really as a result of films like 'Nightmare on Elm Street,' is that we're getting into what I have coined as 'rubber reality,' which is films that deal with the way that reality can be distorted and permeated, going into dream states and states of madness and all sorts of strange illusions, that haven't been treated in films since Cocteau, I think. So in that sense, it's becoming less blood and guts and more hallucinatory, which I think is basically what films are, anyway."

Craven's baton gets picked up by an old friend

Producer and director Sean S. Cunningham was friends and partners with Craven when both were starting out in the business, and collaborated together while making "The Last House on the Left." Cunningham even directed a brief scene in "Nightmare" while visiting his old pal on set.

Famously, Cunningham also unabashedly ripped off "Halloween" when making his 1980 opus "Friday the 13th," the movie that proved the slasher formula was both durable and profitable. Never one to miss out on a trend, Cunningham produced a movie a couple of years after "A Nightmare on Elm Street" directed by another pal of his and Craven's, Steve Miner. That movie is entitled "House," a title which may or may not be directly referencing the 1977 Japanese horror film of the same name that could certainly bear the "rubber reality" moniker.

The 1986 "House" is far more a child of "Elm Street" than arthouse throwback, utilizing a lot of Craven's brand of surrealism for its flights of horrific fancy (not to mention a bunch of actual foam rubber in creating its various monsters). Essentially, "House" does for rubber reality what "Friday the 13th" did for slashers: it establishes a repeatable structure for surrealism (a quality that, in other cases, is defined by its lack of definition), making it clear that there is a "real" world and a "dream" world that is permeable, where each can affect the other while their existence is made more objective than subjective.

The nightmares that followed

As the "Nightmare on Elm Street" franchise gained steam, a series of films were released that seemed eager (to put it charitably) to adopt rubber reality in order to create their very own Freddy Krueger. 1987's "Scared Stiff" involved the cursed spirit of a colonial slave owner menacing a modern-day family, 1988's "Dream Demon" conflated the life of Princess Diana with a girl's abuse-laden past, and, also in 1988, "Bad Dreams" made a deceased cult leader into a Freddy-like demon haunting the halls of a psychiatry ward.

Some sequels even made a turn onto "Elm Street," such as 1987's "Hello Mary Lou: Prom Night II," which ditches the "Halloween"-inspired slasher trappings of the original and creates a female Freddy figure. While Don Coscarelli's 1979 "Phantasm" was an early proponent of dream logic, it's easy to believe that the execs at Universal Pictures were thinking of "Elm Street" money when they produced his "Phantasm II" in 1988.

Horror maestro Clive Barker was able to adapt his novella "The Hellbound Heart" into the masterful "Hellraiser" in 1987, in part because the story's approach to the realm of the demonic Cenobites had a distinct rubber reality flavor to it. 1988's "Hellbound: Hellraiser II" goes further into "Elm Street" territory, presenting a literal labyrinth akin to Freddy's dreamland. By the time the series' lead Cenobite, Pinhead (Doug Bradley), began wisecracking up a storm in 1992's "Hellraiser III: Hell on Earth," it was clear the franchise was stuck chasing Freddy's wake.

Ironically, Wes Craven's own attempt to replicate the success of Freddy and the "Elm Street" series flopped. 1989's "Shocker" tries to apply the Freddy formula — rubber reality, various demonic superpowers, a taste for bad puns — to a new character, the serial killer and TV repairman Horace Pinker (Mitch Pileggi). While the movie has a lot of standout scenes and imaginative ideas at play, it betrays Craven's own rubber reality style from "Elm Street," presenting as it does far too many contradictory "rules" for the surrealistic bending of reality.

Craven regains his stride, and rubber reality continues

Fortunately for Craven and horror aficionados alike, the director was able to return for the 7th film in the "Elm Street" series, 1994's "Wes Craven's New Nightmare." That movie not only re-established the unsettling and beguiling rubber reality from Craven's first "Elm Street" to a series that had since become wacky and diluted in its depiction of dream logic, but was the first salvo in Craven's postmodern look at the horror genre, a theme he would explore further in another mega-hit, "Scream."

As I said before, surrealism in horror films does not begin nor end with Craven, but his influence on its usage, style, and technique is undeniable. Films as recent as James Wan's "Malignant" and Leigh Janiak's "Fear Street" trilogy owe a debt to Craven's interweaving of reality and dreams. As Freddy himself may say to subsequent rubber reality movies, "You are all my children now."