Why Mike Flanagan Gets 'Constant Pushback' For His Signature Monologues

Ever since his passion project/victory lap with his 2021 miniseries, "Midnight Mass," Mike Flanagan has quickly become one of our most beloved horror auteurs working today. Emphasis on "working!" Flanagan never stops working. He has written, directed, produced, or edited numerous projects every year since 2016, during which time he directed three different feature films.

With a wonderful acting troupe he regularly works with and a refreshingly empathetic and inspired approach to the horror genre, Flanagan keeps raising the bar for himself. This is the man who dared to make a sequel to Stanley Kubrick's "The Shining" and succeeded in making it something that stands on its own.

One of Flanagan's most identifiable stylistic markers is his novelistic use of soliloquy and monologue. You know you're watching a Flanagan project when the pace slows down and one character in the scene glows amid his hazy visual style to deliver a killer speech on depression and trauma. We could watch hours of these things, but unfortunately, it's not quite to every viewer's taste.

In an interview for Discussing Film on his newest series, "The Midnight Club," Flanagan was asked about his enthusiasm for monologues, in which he answered that he finds it a wonderful art form in itself, even if he gets "constant pushback" about it from some audiences over it.

Flanagan's love for the monologue runs deep

Flanagan's admiration for the monologue has been present for many of his films and series, but his love for the storytelling device was born out of respect for his cinematic and theatrical inspirations.

"I think it's a dying art, unfortunately. I was a theater minor so I have always loved theater. I've performed in theater, I was terrible at it but I loved it. Soliloquy and monologue, I think, are art forms in and of themselves. I respond to them when I see it done well. It makes an incredible impact on me. When I watched 'Paris, Texas' for the first time and saw Harry Dean Stanton drop that eight and a half minutes at the end of that movie, it was revelatory and immersive and immediate for me in a profound way. I love an opportunity to employ those tools and to see an actor, if an actor is capable of it, really grab the audience by the hand and walk them through a full journey."

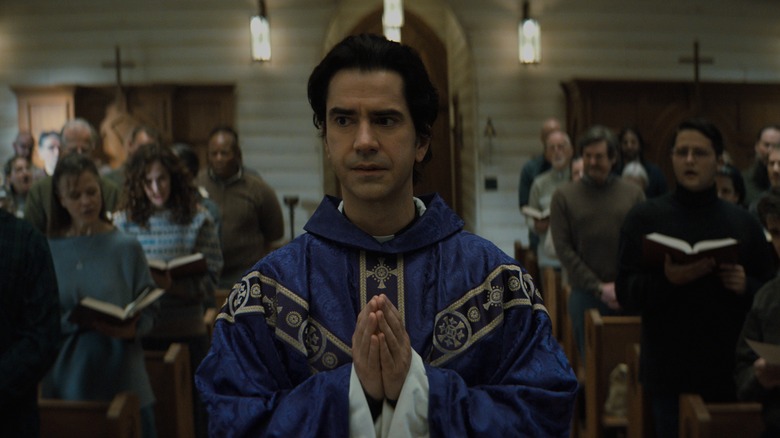

The filmmaker's love for the monologue reached its apex in "Midnight Mass," which expanded Flanagan's usual themes of grief and mortality and tied them into the toxicity of organized religion. The lengthy monologues mirrored religious sermons, allowing the characters to have an open conversation about their own relationships with faith.

In his newest series "The Midnight Club," the story follows a group of ill teenagers who get together and tell each other horror stories. While, yes, there are lengthy segments of characters speaking, these are much more broken up by moments of dialogue and cutaways into individual stories. It's quite a departure for the usual Flanagan monologue, but it's a logical evolution for the tone of the show.

Long live the Flanalogue!

"My favorite version is when there aren't cutaways. It's very theatrical. ["The Midnight Club"] isn't lent to that. That was one of the big differences in the way we approached the writing on a show like this." Flanagan explained. "It was way more dialogue intensive than it was monologue intensive. So some stories lend themselves to that very well. I wouldn't change a word of "Midnight Mass," for example, but this was different."

In a media landscape that's obsessed with instant gratification, Flanagan often finds some resistance to his gradual, slow-burn type of storytelling, especially from the corporate side of filmmaking. "I get constant pushback about it because I think the executive world and the marketplace have short attention spans," Flanagan continued, "and we were conditioned by a lot of entertainment, to go from thing, to thing, to thing, to thing, and faster and faster cuts, and less and less rewarding of patience.

Flanagan's horror is ultimately rewarding and fresh because it does something new and contemporary with ghost stories. He understands that horror is an inherently empathetic genre, that universal fears are discovered from a place of empathy. In Flanagan's unique, compassionate take on horror, there's always space for his characters and world to slow down and breathe. "I will always push back against that trend. That is the hill I'm willing to die on, and I may end up dying."

Trevor Macy also chimed in during the interview with a cute nickname for Flanagan's writing style, "We call those Flanalogues."

Long live the Flanalogue!