Was Bleach Ever Good?

"Bleach" began its run in the popular comics magazine Shonen Jump in August 2001. It was adapted into an anime three years later in October 2004, and quickly became one of the most popular anime and manga in its age bracket. Fans would refer to "Bleach" and its two Jump peers, "Naruto" and "One Piece," as the Big Three.

"Bleach" always boasted the lowest sales numbers of the three, especially in Japan where "One Piece" was king. But "Bleach" made up for this by being the most stylish comic of its day. Its character designs, fight sequences and paneling had a certain je ne sais quoi that kept it relevant against heavier hitting opponents in the magazine. The fact that its hero, Ichigo, was a jaded teenager from the beginning, rather than a rambunctious child like Naruto or Luffy, appealed to a fanbase that was going through its own adolescence.

"Bleach" has returned to television this fall in order to adapt the final arc of the manga. But the world has changed since the original series went off the air in 2012. Of the original Big Three, only the "One Piece" comic is still running in Shonen Jump. Anime streaming has become mainstream, and you can now legally read Shonen Jump comics on your phone rather than buying them from Barnes & Noble like in the old days. New Jump series like "My Hero Academia" and "Jujutsu Kaisen" captured the next generation of fans. "Bleach" is now an object of nostalgia, rather than the peak of fashion. There has never been a better time to weigh what the series accomplished, and ask: does it hold up?

Velonica

For those who don't know, "Bleach" is the story of Ichigo Kurosaki, a teenager who can see ghosts. When he encounters Rukia, a Soul Reaper (or "shinigami") who helps the souls of the dead pass on to the next world, Ichigo inherits her powers and must fight malevolent spirits called Hollows. For the first six volumes, "Bleach" introduces us to Ichigo's high school classmates, many of whom have mysterious abilities of their own. But then Rukia's fellow Soul Reaper allies come knocking, spiriting her away to be executed for the crimes of giving her abilities to a human. Ichigo and his friends break into the Soul Society, the city of the dead, to save Rukia's (after)life. There they encounter the thirteen captains of the Soul Society, whose zanpakuto swords hide powerful abilities.

The story of "Bleach" is not particularly original. Tite Kubo was reportedly inspired by "Saint Seiya," which also features larger-than-life characters, themed weapons and armor and a mythological motif. You could also draw comparisons with "Yu Yu Hakusho," which had juxtaposed cool teens with Japanese spirits back in 1990.

But the style of "Bleach" is something else entirely. Kubo told stories about teenagers whose proportions were realistic compared to the expressive cartooning of "Naruto" and "One Piece." He dressed them in clothes that readers at the time wished they owned themselves. Starting with the introduction of the Soul Society captains and their squads, Kubo packs the series with dozens of new characters. Yet each is distinct in look and personality, even when (as Super Eyepatch Wolf observes in his video) they all wear the same uniform. The diversity and charisma of the cast, coupled with the number of potential pairings, gave fans plenty to work with.

D-tecnoLife

"Bleach" may be best known for its anime adaptation, which aired from 2004 to 2012. The series was directed by Noroyuki Abe, who had previously brought the "Yu Yu Hakusho" anime to life. The music was handled by Shiro Sagisu, the composer of "Neon Genesis Evangelion." His score is eerie but distinctly modern, shifting between discordant synths and cheesy rock songs. Most important of all to the "Bleach" anime are its opening and ending credits sequences, which maintain a high standard of excellence from beginning to end. The show's second opening theme, "D-tecnoLife," was the first single of classic J-rock band UVERworld. It remains, as I wrote in a Crunchyroll ranking of "Bleach" openings, the definitive "heroes running determinedly towards the camera" sequence.

Outside of the credits sequences, though, I can't say if the "Bleach" anime is worth revisiting today. The demands of a weekly animated series flatten out the appeal of Kubo's art. There are moments of neat animation, including an early appearance by "Mob Psycho 100" director Yuzuru Tachikawa. But the best episodes of "Naruto" far exceed anything "Bleach" has to offer. Even "One Piece," whose animated adaptation struggled for years to match Oda's vision, managed one excellent film in Mamoru Hosada's "Baron Omatsuri and the Secret Island." The "Bleach" anime elicits as much nostalgia as any of the Big Three among its fans, yet may be the weakest of all of them.

After Dark

The manga fares better. Kubo has two great gifts as a comics artist. The first is an eye for composition. As Kubo says in an interview with About, "I pause the action and rotate the character and find the best angle, and then I draw it." By changing angles dynamically between panels, Kubo creates dynamism even when his characters are just standing around talking. His environments are dull compared to peers like Oda, but his staging is so effective that you don't notice. Kubo's second gift is for title pages, which become increasingly abstract as the series continues. David Brothers, one of the hosts of "Mangasplaining" podcast, has said that "Kubo has a knack for designing title pages or sequences that are bar-none the absolute best in comics." I agree with him.

So why do I find "Bleach" to be thin gruel compared to "One Piece," or even "Naruto?" "One Piece" may be the most effective Jump comic ever at balancing week-to-week adventure with a broader narrative arc. Its heroes are simple but their wants and needs are always clear to the reader. "Naruto" is spottier, but its best moments wring tears of joy or sadness from even the most jaded manga fan. By comparison, "Bleach" doesn't have much going on outside of its aesthetics. Once "Bleach" reaches the Soul Society arc, it hits the same beats for the next sixty-eight volumes. Kubo's designs and layouts continue to improve, of course. But the characters rarely grow or change in ways that matter. The battles grow in scale but not in concept. It slowly sinks in that the stylish sword duels of "Bleach" are repetitive and pointless.

Ranbu no Melody

The greatest challenge any Shounen Jump series must face is to remain consistently entertaining for as long as it runs. One way to do this is to create a varied "possibility" space in which a variety of stories are possible. The many islands of "One Piece," the all-encompassing Nen system of "Hunter x Hunter" and even sports stories like "Haikyuu!!" pass this test. Even when these series stick to the Jump formula of friendship, struggle and victory, they capture the audience's attention through variation. "Bleach" cannot do this. Its world is thinly developed, limiting the kinds of stories Kubo can tell. Its characters have fun and stylish powers, but battles rarely require them to use their powers creatively. Ichigo is an effective self insert character for teenagers, but his motivations grow increasingly specious over the course of the series.

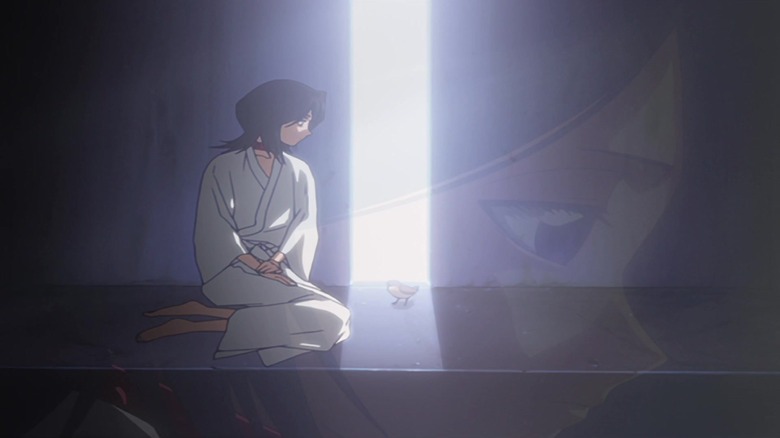

"One Piece" is about dreams overcoming tyranny. Luffy punches petty tyrants through larger and larger government buildings to ensure that his friends have what they need to be happy. Every time Luffy is in a fight, we know exactly what he is fighting for and why. "Naruto" is about loneliness. Naruto desperately wants to prove himself after being abandoned by his village. His friend Sasuke sacrificed his childhood in order to take revenge on his murderous brother. Even when the story of "Naruto" falls apart, the emotional beats often ring true. "Bleach," on the other hand, is about nothing. Ichigo fights for Rukia's sake, at first. But eventually he and his friends fight for the sole reason of fighting. Kubo tries to incorporate a guiding theme later on, but it doesn't take. He said that he wanted to "draw Soul Reapers wearing kimono." In the end, that's all "Bleach" ever amounts to.

Rolling Star

Is that such a bad thing, though? "Bleach" may be nothing more than a series of drawings in which Soul Reapers wear kimono. But it's a very well drawn series of drawings in which Soul Reapers wear kimono. David Brothers says in his piece that "what Kubo does well is dig deep into the idea that style can be substance, that something beautiful is able to inspire enjoyment, too." "Bleach" may be increasingly boring as it continues, but it is always beautiful. Kubo's passion for his art can be seen in every elaborate character design and stunning layout. The cast of "Bleach" is far too large, but their variety reflects the fun Kubo must have coming up with new concepts for each squad of heroes and villains the reader meets along the way.

We live in a world after "Bleach." "Jujutsu Kaisen" borrows its focus on urban teenagers and grotesque spirits. "Demon Slayer" outfits its own superpowered Demon Slayer Corps in kimono uniform. Even something like "Chainsaw Man," which is nastier and more avant garde than "Bleach" ever was, exists because "Bleach" (and its predecessors, like "Yu Yu Hakusho") laid track for Jump stories about jaded teenagers. "Bleach" will never again be the height of cool. Its days as the cool older brother of Jump comics are over. But I'll always remember "Asterisk," its first opening sequence, which set the tone. Or "Rolling Star," its fifth, which still evokes brightly lit nights and adolescent angst. When Shiro Sagisu's music played in the trailer for the new season, I got goosebumps. So it goes. "Bleach" will never be my Number One, but I respect it.