How An Army Of Extras In The Brutal Heat Created Close Encounters Of The Third Kind's Mothership Scene

It's hard to imagine that even one frame of celluloid in Steven Spielberg's alien epic "Close Encounters of the Third Kind" could be out of place. The intimate and sometimes difficult dramatic family scenes dovetail beautifully with the astounding visual effects that beckon Roy Neary (Richard Dreyfuss) to venture out into the cosmos, leaving his old life behind. "E.T" and "Close Encounters" both deal with the effects of separation and divorce while also marveling at the endless possibilities that exist out there in the universe. Whether it be a curious child, like Barry Guiler (Cary Guffey), or a preoccupied husband like Roy, there is no better metaphor for showing the distance between us than a giant spaceship abducting our loved ones and beaming them millions of miles away.

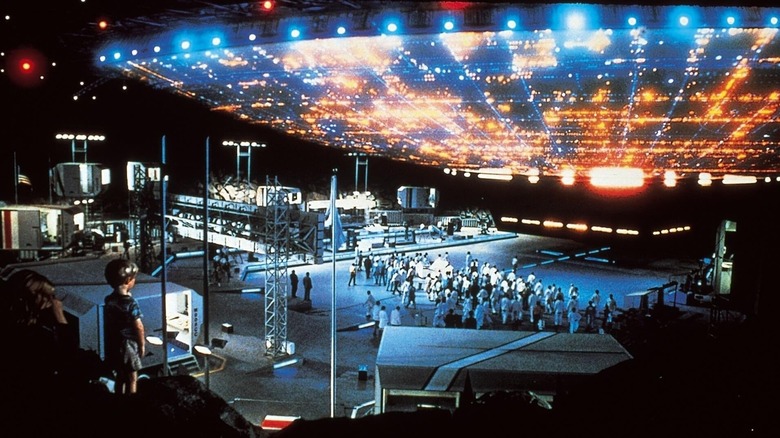

The arrival of the mothership in "Close Encounters" is one of the most wondrous finales in American film history largely because it grounds the extraterrestrial elements with real believable characters, from the main protagonist to the nameless scientists working tirelessly on top of Devil's Tower. To make the entire sequence work, dozens of well-trained extras were needed and the mothership's arrival would need to be covered from multiple angles. For such a perfect ending, the amount of things that could have gone wrong is absolutely staggering. In honor of the gargantuan amount of effort needed to pull off the mothership scene, we're diving into author Michael Klastorin's book "Close Encounters of the Third Kind: The Ultimate Visual History" published by Harper Collins to look deeper into the grueling conditions during the shoot.

Do the aliens have air-conditioning?

Bringing such a fantastically complicated scene into reality required a seamless blend between the live-action and the groundbreaking visual effects. In what must have felt completely unnatural as a living, breathing human, the extras had to duplicate their exact actions over and over for multiple takes in order for Spielberg to capture the action from every possible angle. In the film's coffee table "Visual History" book, Klastorin shares how first assistant director Chuck Myers made that mindless repetition feel more organic. "[He] went to all of the cubicles the technician extras were posted at, gave each of the extras a character name, and invented specific stories for them. He also showed them how to operate various pieces of prop scientific equipment and patiently explained the movements they would need to repeat, take after take."

In the film, Dreyfuss' character Roy mentions the Box Canyon and the location is a main centerpiece in "Close Encounters." Referring to the canyon, Jillian (Melinda Dillon) famously says "I never imagined that in my paintings." Although they're supposed to be at Devil's Tower in Wyoming, the actual Box Canyon scenes were shot in Mobile, Alabama with on-set temperatures rising to over 100 degrees. The cast and crew were melting in the middle of July and the filament from multiple film lights was only making it hotter. As Klastorin writes:

Air conditioning would be provided whenever possible, but the sheer enormity of the set prevented the units from providing comprehensive cooling for the entire area. Additionally, the air conditioning had to be regulated as it would dissipate the output of the smoke machines which filled the set with an appropriately atmospheric haze each morning.

A family affair

"Close Encounters of the Third Kind: The Ultimate Visual History" also makes note that even Richard Dreyfuss' father, Norman, was on set with over 150 other extras. Undeterred by the conditions, he appeared alongside actor Bob Balaban and French auteur François Truffaut in the finished film. The fact that his father was a small part of Spielberg's fantastical family film makes the filmmaker's own connection to his family all the more poignant.

In a memorable moment during an interview on "Inside the Actor's Studio," host James Lipton posited a question to Spielberg that was quite profound about the director's parents. Spielberg's father was a computer scientist and his mother was a musician. Lipton observed that the scientists in "Close Encounters" use music to communicate to the mothership using the John Williams iconic five-note theme. In that exchange, the two are, as Lipton says, "allowed to speak to each other." "I'd love to say, you know, I intended that to be and I realized that was my mother and father but not until this moment," responded Spielberg. Maybe he was too busy making sure that the entire sequence would actually work instead of doing the "real" work necessary for a therapy session that wouldn't end up happening until the "Actor's Studio" conversation over twenty years later.