WALL-E Ending Explained: It's Good To Be Home

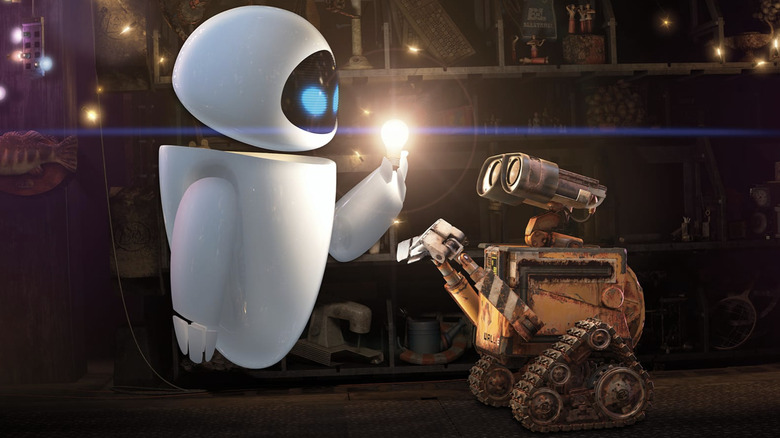

Few films offer as romantic a view of a bleak dystopian future than "WALL-E." Written and directed by Andrew Stanton, the movie is one part a playful romance between (literally) star-crossed robot lovers, and two parts a depressing vision of the future. But it's the blossoming infatuation WALL-E has with EVE, his first companion other than a cockroach, that takes center stage. It's through this relationship that the film addresses many of its other themes, from the consequences of rabid materialism to environmental degradation.

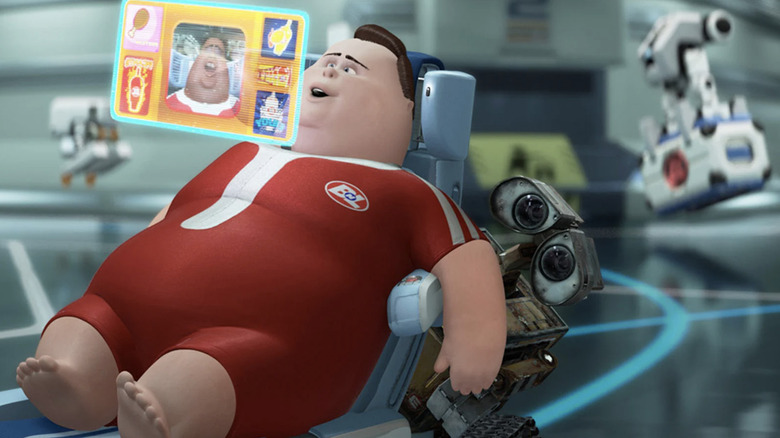

Whether we like it or not, "WALL-E" has become an unsettlingly prescient rendering of our present future — one in which large consumer corporations like "Buy N Large" feed a gluttonous demand for shiny new tech at horrendous cost to our planet. Or where solutions take the form of plans to launch ourselves (or whoever can afford it) into the cosmos to wait out the crisis (or find another planet to wreak all the same mistakes upon) instead of just curbing our cravings.

There's also no small irony in the fact that humanity's salvation ends up being two advanced versions of the very technology that helped make Earth uninhabitable. Part of this is owed to the fact that "WALL-E" doesn't seek to demonize scientific advancement but rather its misuse, especially as a commodity created wastefully to entertain the masses. And by the end of the film, it's these two "little robots that could" who've steered humanity back on a proper course: Returning home to Earth.

WALL-E teaches humans how to reconnect with one another

In the DVD commentary, Stanton makes it clear he never intended to make a film solely about consumerism. Instead, he wanted it to focus on the ways in which we pry ourselves from what he called "life's programming." The journey of WALL-E is indicative of that theme: He's a robotic Sisyphus eternally stacking the garbage humankind has left behind, until he's shaken from his routine by the arrival of EVE. In following her out of love to the Axiom, he reveals an empathy long absent still exists on Earth, and like the plant his robot sweetheart carries, he shares it with humanity.

For one, he helps initiate quite possibly the first romance on the Axiom in generations between the two humans, Mary and John. Not only do they share a tender moment watching WALL-E and EVE dance in space, but they can also be seen later attempting to enjoy a pool neither of them ever noticed before. It's a beautiful piece of irony to have a robotic relationship spur a human one, but "WALL-E" has no qualms about the source of such emotions — only that they draw us all closer together.

Yet the most dramatic transformation comes from Captain McCrea, who manages to stand up on his own two feet in defiance of the nefarious Auto, undoing generations of evolutionary neoteny. It's a transformation that's later mirrored by WALL-E after his injuries revert him to a version that doesn't recognize EVE and returns to purposelessly stacking garbage. A kiss reboots him back to his personable self, though, revealing, like with McCrea, that such empathy can override all of life's programming.

Humanity develops a better relationship with technology

The ending of "WALL-E" signifies, however comically neat or overtly optimistic, that humanity is now ready to redeem the mistakes of generations past. Through the actions of WALL-E and EVE, they've been shaken out of their technologically induced solipsism with a mind for repairing Earth — which, as the illustrated end credits reveal, they plan to do unironically with the help of machines. This would be concerning, a sign of humanity taking baby steps to another pitfall, if not for the actions of Captain McCrea.

As much as the consumption of tech contributed to whatever climate crises made Earth inhospitable for organic life, that's never been the real enemy. Instead, it's important to remember the human demand and desire that fueled such supply. Even when it comes to Auto, things become slightly grey given that they're just operating from a directive given by a human. When McCrea shuts down Auto to save WALL-E, he also asserts favor for any other piece of technology that exists to help humanity thrive responsibly. It's also a powerful metaphor for humanity finally severing its toxic relationship with technology in favor of a far healthier one, and hopefully indicates they won't make the same mistakes when they've returned to Earth.

It all hinges on the survival of a single plant

Even though Stanton didn't intend "WALL-E" to be a statement about consumerism, in modeling it after our own world, it's inevitably a large part of it. It's the reason, after all, the movie's world is so exceptionally trashed and devoid of all plant life. That is, until WALL-E discovers a solitary plant and places it in a boot with some dirt.

Nostalgia, already a heavy theme throughout the film, is imbued in the plant as well. WALL-E is a hopeless romantic who watches "Hello, Dolly!" and collects sentimental artifacts of the human race. His care for the plant is an extension of those feelings, and the plant itself becomes this heartbreaking and visually stirring representation of what's been lost thanks to humanity's greed. It's a relic WALL-E protects as devotedly as he does EVE, and he aids in fulfilling her directive to get it to the remnants of humankind.

It's no coincidence that such weight is placed on this one helpless piece of vegetation. At the end of the film, the plant is the literal reason why the Axiom heads back to Earth, but it's far more important than just a plot device. It's a subtle reminder that when the planet is dead and the privileged few have cast off their moorings to escape into the stars, the greatest loss will not have been our luxuries (sentimental or not), but the ecosystems we callously wrecked in our indifference.