Peter Jackson's Approach To Dead Alive's Zombies Came Straight From Monty Python

Long before his involvement in a series of elf-populated, jewelry-based hiking movies, New Zealand filmmaker Peter Jackson won hearts as the director of gloppy, vomitous, utterly repellant midnight grindhouse fare like "Bad Taste," "Meet the Feebles," and "Braindead" (known as "Dead Alive" in North America). Jackson's early films have an excited, adolescent joie de vivre that his later digital-forward technical exercises lack, and are perfect for naughty teenagers who think that films like "Evil Dead 2: Dead by Dawn" don't go far enough.

"Dead Alive," easily one of the goriest films ever made, is constructed like a comedy film and has a premise that wouldn't feel out of place in a Saturday morning cartoon. Lionel (Timothy Balme) lives with his controlling and guilt-trip-dispensing mother Vera (Elizabeth Moody) in 1950s Wellington. Lionel is beloved by a local shop owner named Paquita (Diana Peñalver) who believes, courtesy of tarot cards, that they are destined to fall in love.

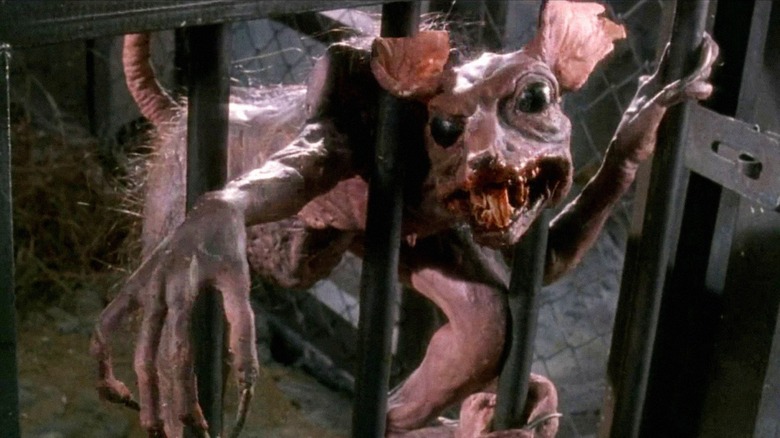

When a Sumatran rat-monkey bites Vera, it gradually turns her into a flesh-hungry, dripping zombie. Lionel, rather than destroy his monstrous mother, arranges to buy some animal tranquilizers from a Nazi doctor(!) and keep her sedated, tied to a chair. This doesn't prevent the zombie outbreak from spreading, and it's not long before Lionel is also tending to a zombie nurse, a zombie priest, a gang of zombie hoodlums, and a zombie baby.

"Dead Alive" climaxes with Lionel lifting a lawnmower up off the ground and walking its spinning blades through an army of zombie partygoers — limbs flying everywhere.

Back in 1992, Jackson explained to Film Threat that his approach to "Dead Alive" had less to do with "Night of the Living Dead" and everything to do with "Monty Python and the Holy Grail."

Nothing is too much

The final sequence of "Dead Alive" is more than just the lawnmower massacre. It's a wild, multi-room bloodbath of epic proportions. A food processor is used to blend a zombie's head. Kitchen knives are used to great effect. A lawn gnome finds its way into a zombie's neck hole. A zombie's head is pinned to a light socket, causing its whole face to illuminate. In what might have been the film's most difficult special effect, a disembodied set of lungs and intestines — alive and hungry — attacks Lionel in a bathroom. Oh yes, and there is a 15-foot-tall giant zombie mutant monster that sucks Lionel into its goo-engorged abdomen. "Dead Alive" is a gnarly, gnarly film.

Film Threat asked Jackson if they were concerned about excess. Jackson wasn't so much concerned with going too far as he was staying ahead of the curve. There had already been any number of extremely gory zombie films in the years leading up to "Dead Alive" — there were three films in the "Zombi" series in 1988 alone — and Jackson seemed eager not to appear passé. Indeed, one of his zombie gags was in a recent Ken Wiederhorn movie. He said:

"[I]t was a bit tough to come up with new gags. Francis Walsh, Stephen Sinclair and I wrote the original script for 'Braindead' five years ago while still shooting 'Bad Taste' and it's been quite frustrating to see a lot of the gags we wrote back then turn up in other movies in various forms. Like one where a zombie is cut in two but still crawling along, I saw that in 'Return of the Living Dead II.' So along the way we had to keep coming up with new stunts just to stay on top."

Bloody funny

Jackson has certainly never played anything small, and his theory about gore was that if it was extreme enough, then it would have to be taken as comedic. True horror, he seems to feel, is more about fear that exists in the mind. One may be afraid of having their blood shed, but no one has a reasonable fear of being strangled to death by a living ball of greasy intestines. An undead corpse slowly shambling toward you is going to be scarier than a head in a blender.

Jackson learned this 18 years prior when he witnessed King Arthur (Graham Chapman) slice the arms and legs off of the Black Knight in "Monty Python and the Holy Grail." The Black Knight is reduced to a torso, bleeding all the while. The joke lies in his tenacity, of course, but also the copious spurting blood that he and Arthur seemingly ignore.

"[T]he more over-the-top a gag is, the funnier it will be and I don't see a problem with that so long as it's properly executed. Besides, the real, creepy horror stuff usually doesn't have a lot of blood in it. Going that way disturbs people a lot more than a gory film because it has to be taken seriously. You can't defend against it. But if you go way beyond the saturation point, there's no way people can be offended or shocked. They just have to laugh. Monty Python first made that apparent in 1974 with 'The Holy Grail'. For the first time, arms and legs were chopped off for laughs. I'm just carrying on with that."

Given the brazen slapstick tone of "Dead Alive," and its placement far beyond Jackson's "saturation point," the two films would make a dandy double feature.