The Classic 1920s Silent Film That Inspired The Joker

Riddle me this: what do the Joker and "Casablanca" have in common? If you answered, "Conrad Veidt," then you've survived the first deathtrap, much like the Dynamic Duo coming out of a cliffhanger ending into the next episode of the 1966 "Batman" TV series.

80 years ago, Veidt received fifth billing in "Casablanca" after Humphrey Bogart, Ingrid Bergman, Paul Henreid, and Claude Rains. His movie career, however, dates back even further than that to the silent era. In "The Man Who Laughs," the 1928 silent film helmed by German Expressionist director Paul Leni, Veidt shared top billing with Mary Philbin, and the indelible image of his grinning face left a mark on both movie history and comic book history.

The creation of Batman's greatest nemesis, the Joker, is attributed to writer Bill Finger and artists Bob Kane and Jerry Robinson. Over the years, conflicting accounts arose over who really originated the first idea for the character. One thing no one much disputed was that Joker's genesis had something to do with "The Man Who Laughs."

For his part, Finger recalled having a copy of Victor Hugo's eponymous novel and cutting a picture out of the book as a visual reference for Kane. When an Entertainment Weekly writer interviewed Kane for a 1994 issue of the magazine, Kane said that the picture he saw was a photograph of Conrad Veidt, which later appeared in his biography, "Batman & Me." That image of Veidt as the smiling Gwynplaine from "The Man Who Laughs" is rather well-known now, but if you go back and watch the movie, it becomes clear that the comic book creators responsible for Joker used Veidt's appearance as a jumping-off point for an altogether different sort of laughing-man tale.

Gwynplaine in The Man Who Laughs (1928)

In "The Man Who Laughs," Gwynplaine is a wholly sympathetic figure, which immediately sets him apart from the homicidal maniac Joker would become. We first meet Gwynplaine as a child, whereupon he becomes a victim of the Comprachios, described as "traders in stolen children," who are known for "practicing certain unlawful surgical arts, whereby they carve the flesh of these children and transform them into monstrous clowns and jesters."

The carving of Gwynplaine's face is relayed through intertitles by Barkilphedro (Brandon Hurst), the court jester of King James II. It's part of the punishment for Gwynplaine's noble father, who is sealed up in an iron maiden, leaving his son to be literally scarred for life by the Comprachios. They desert him at the age of 10 and he wanders cold and hungry, finding a blind orphan baby in the snow and then finding a home for them both with the showman Ursus (Cesare Gravina).

The way Barkilphedro is characterized ("All his jests were cruel and all his smiles were false") is actually closer to what fans might think of when they think of the Joker. As for Gwynplaine, he's a mountebank, not a madman, in "The Man Who Laughs." The adult Gwynplaine remains shy about his scars and often wears a scarf over his mouth or covers his hand with it.

The blind baby grows up to be Philbin's character, Dea, who, together with a wolf named Homo (played by Zimbo the Dog), gives Gwynplaine unconditional love and support, making earnest pronouncements like, "God closed my eyes so I could see only the real Gwynplaine!" Together, they tour the countryside in fairs, where Gwynplaine performs as the Laughing Man and his freakish mien makes him the laughingstock of audiences.

The clown enters his court

Because of its Expressionist shadings and because "The Man Who Laughs" was produced and distributed by Universal Pictures, it is sometimes confused for a horror film and Gwynplaine is sometimes considered a Universal Monster. However, Veidt's performance predates that of Bela Lugosi in "Dracula" and Boris Karloff in "Frankenstein" by three years. The real onset of such Universal characters would come in the 1930s. And though he is surrounded by clowns and does cake on white make-up like Joker before performing on stage, Gwynplaine is only a monster in the same sense as Lon Chaney's tragic Quasimodo in "The Hunchback of Notre Dame" (another 1920s silent film adaptation of a Victor Hugo novel).

Instead, "The Man Who Laughs" emerges as more of a melodrama that toys with the audience's desire to see the lovers, Gwynplaine and Dea, reunited. They are separated after the Comprachio surgeon who disfigured Gwynplaine as a boy chances upon him again years later at the fair, setting in motion the events whereby the Laughing Man's noble lineage comes back into play and sees him welcomed as the Incomparable Gwynplaine into the House of Peers, where Queen Anne (Josephine Crowell) herself sits enthroned.

"Make way for a Peer of England," someone says, with the word "peer" doubling as a signifier for restored humanity and social class on the part of the misunderstood monster. Queen Anne wants to marry Gwynplaine off to the Duchess Josiana (Olga Baclanova), but he refuses in the face of continued laughs from his new royal audience. "I protest!" he says. "A king made me a clown! A queen made me a lord! But first, God made me a man."

The Joker is nicknamed the "Clown Prince" of Crime, and in Gwynplaine's story, we see the model for that.

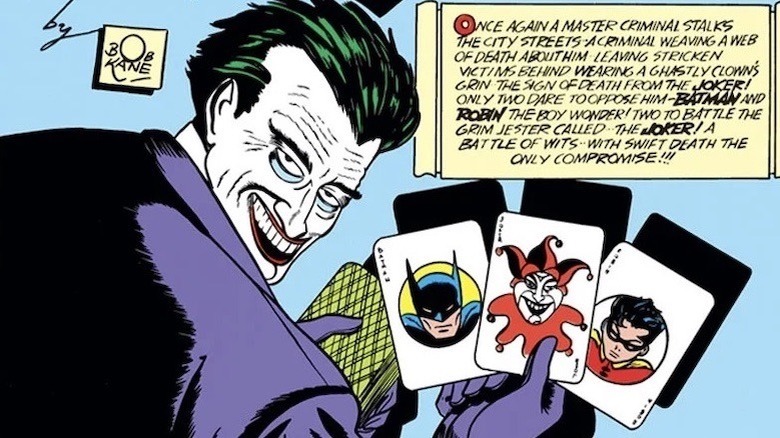

The grim jester in Batman #1

The final insult to Gwynplaine — or highest honor, depending on how you look at it — is that a single image of him would inspire one of the greatest comic book and movie villains of all time. Like Gwynplaine, the Joker is "a man with a changeless, mask-like face." A 13-page story in "Batman" #1, published by DC Comics in 1940, introduces him as a "grim jester" and "diabolical killer" who wears a permanent smile "without mirth."

The Joker's initial M.O. is to pronounce the exact hour of a man's death on the radio while declaring his intent to steal a diamond, ruby, or necklace. He ends each message with the words, "The Joker has spoken," as if to differentiate himself outright from Veidt the silent film star, who obviously couldn't speak aloud onscreen until the advent of talkies.

At-home listeners initially think it's a gag when Joker interrupts their regularly scheduled broadcast to announce the midnight deadline for his first victim. One of them likens it to "that story about Mars the last time," an allusion to the panic caused by the "War of the Worlds" radio drama that "Citizen Kane" director Orson Welles staged in 1938.

It's not just millionaires and judges Joker kills, but also fellow criminals. The way he does it is by "leaving stricken victims behind wearing a ghastly clown's grin, the sign of death from the Joker." Here we see how the victim, Gwynplaine, morphed into something more like his victimizers, the Comprachios, in the figure of Joker. Batman theorizes Joker is using "some sort of drug that pull[s] the muscles of the face." Confronted with him, he recognizes, "I've at last met a foe that can give me a good fight."

'You know how I got these scars?'

In "Batman" #1, a policeman leaning in over a body observes, "Grotesque! The Joker brings death to his victims with a smile!" Later, Joker shows himself to be a master of disguise, posing as the white-haired, mustachioed police chief. Heath Ledger's Joker in "The Dark Knight," who bears facial scars like Gwynplaine, would affect a similar masquerade during a police funeral, while Barry Keoghan's Joker would go even harder on the scars in a deleted scene from "The Batman."

Ledger's Joker sics his dogs on Batman, overpowering him physically like back in 1940. Yet the dogs attack the hero instead of the villain as we see Homo do in "The Man Who Laughs." Of course, "you either die a hero, or you live long enough to see yourself become the villain," and that's what happened with Gwynplaine. He became "a funereal face with eyes radiating hate" in "Batman" #1.

As they fight on a bridge in that issue, we see how "the Joker explodes a haymaker off the Batman's jaw," kicking him in the head and pushing "the helpless Batman" off the bridge. He also gets the drop on Dick Grayson, aka Robin, the Boy Wonder, clubbing him senseless and tying him up, ready to poison him.

Batman thwarts his plan, but the Joker would later murder the Jason Todd version of Robin in DC's "Death in the Family" storyline. Again, this kind of behavior would be totally out of character for Gwynplaine, who was himself hurt as a boy. It just goes to show how easily misjudged a man — or Laughing Man — might be based on one image. As they say in the funnybooks: don't judge a comic book by its cover.