Alex Garland Called In A Favor From NASA For The Science In Sunshine

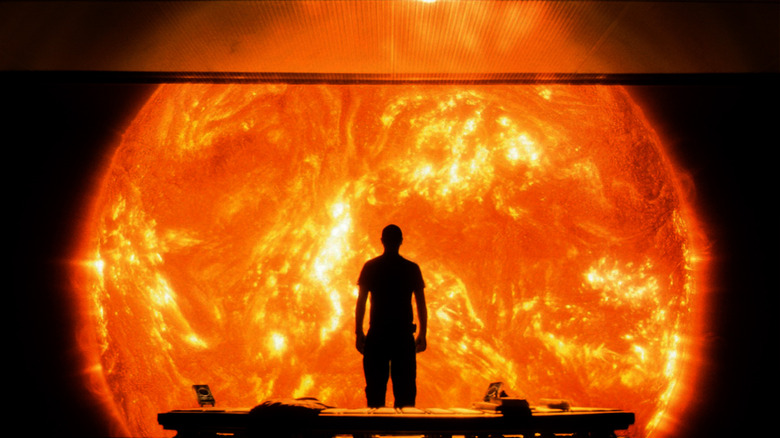

In 2057, the sun will begin to fade out and die. Life on Earth is under threat of extinction. Humankind's solution is to gather what scant fissile materials that are remaining on the planet, construct a powerful nuclear bomb, and launch it into the sun in the hope of "restarting" it. The first mission, Icarus I, has already failed. It will be up to the crew of Icarus II to complete the mission. Like the ship's namesake, they are to fly too close to the sun. They are literally Earth's last hope. The mission will, thanks to various cosmic powers, become increasingly desperate and difficult. Additionally, facing the awesome power of a heavenly body drives most of the astronauts into an existential torpor. The captain often goes to a heavily shaded observation deck to look at the sun directly. In his more ponderous moments, he orders the computer to reduce the viewscreen's shading by an additional hair.

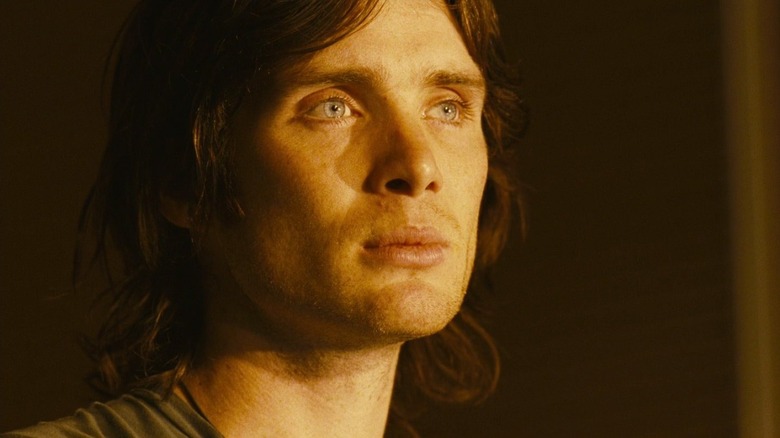

This is the premise of Danny Boyle's 2007 science fiction film "Sunshine," written by Alex Garland. Although structured like a rescue thriller — and an effective one — "Sunshine" has more in common with Andrei Tarkovsky's "Solaris" or Stanley Kubrick's "2001: A Space Odyssey" than, say, "Mission to Mars" or "The Core." More than survival, "Sunshine" is about the human mind's incapacity for containing something so vast as the universe. It is merely too big to fit in the human imagination.

in a 2007 interview with Wired, Boyle remembers hearing about the project for the first time. Boyle and Garland had worked together several times in the past, with Boyle adapting Garland's novel "The Beach" in 2000, and with Garland writing Boyle's "28 Days Later." He and Garland, Boyle said, were very keen on scientific accuracy. NASA journals played a large part.

NASA journals

Garland, Boyle revealed, was always a scientifically and philosophically minded author, a fact that bears itself out in Garland's later directorial efforts like "Ex Machina," "Annihilation" and "Men." It was Garland who initially thought of a story about a dying sun, which Boyle credited to the writer's obsession with scientific journals. Boyle didn't know if there was any one article or journal that interested Garland, but he did acknowledge his partner's interests, saying:

"Alex Garland's a nut for the journals. He sent me a first draft with this amazing high-concept idea: a trip to save the sun. As far as we can find, there's never been a film about the sun, yet it's the single most important thing you could jeopardize."

More importantly, Boyle wanted to acknowledge that Garland's interest in hard science was out of vogue. Modern sci-fi, Boyle feels, has skewed too far away from the "sci" part. Boyle recalls a period when two notable and successful sci-fi films were released within two years of each other, and how the industry definitely skewed toward one of them. Like so many things in Hollywood, "Star Wars" kicked it all down:

"Hardcore sci-fi has gone out of fashion, hasn't it? There was a strong strain of it into the '70s that tried to depict space realistically, but it's been replaced. 'Alien,' one of the great masterpieces, was quickly followed by 'Star Wars.' And 'Star Wars,' of course, led everyone to fantasy sci-fi, that playground where anything goes. You can imagine any creature, on any planet. And they all talk English."

Boyle, of course, mixed up the dates. "Star Wars" was released in 1977, while "Alien" was in 1979.

My brain doesn't really do maths

Boyle, as one might intuit from his tone, prefers the slower, more grounded approach to sci-fi as it was seen in "Alien." Although he admits to fudging certain elements of the technology. As "Sunshine" is set 50 years in the future, at least some speculation would be required. The film's climax did tilt into the fantastical as well as the metaphysical, but Boyle wanted to start from a realistic place. He hired consultants to that very end. He said:

"At the end of the film, there's obviously no way a man could reach out his arm and touch the sun. But the beginning of the film is absolutely based in as rigid a realism as we could do. We consulted NASA about it, and had scientific advisors with us the whole time."

Boyle also admitted an irony. As much as he loves scientific research and technological accuracy, Boyle's more of a "right brain" kind of a person. He is more concerned with story, character, and filmmaking than he is to 100% scientific accuracy. A certain kind of engineering nerd might thrill to mathematical detail (including this author), but Boyle felt no such geeky fealty. At the end of the day, he just didn't want to handle the numbers. Boyle said:

"I loved doing all the science research but I have to be honest: My brain doesn't really do maths. To really do the physics, you need to do the maths, because everything is explicable. You can't encompass it in your brain on a visual level without doing the equations. Ultimately, I had to be loyal to the story. I had no loyalty to the physics."

Boyle's most recent project was the miniseries "Pistol" on FX.