Collateral Ending Explained: A Cab And Subway Ride Through 21st-Century Existence

Forget everything you think you know about Michael Mann's "Collateral," and just think of it as a movie about work culture and 21st-century life, framed through the lens of cab driving and contract killing. Through this reading, the title can be understood as a reference to humans as collateral damage. Mann explored a similar subject in "The Insider," a seven-time Oscar-nominated film about a whistleblower exposing a tobacco company for purposefully making its cigarettes more addictive. In "Collateral," he and screenwriter Stuart Beattie simply went about it in a more indirect, action-oriented manner.

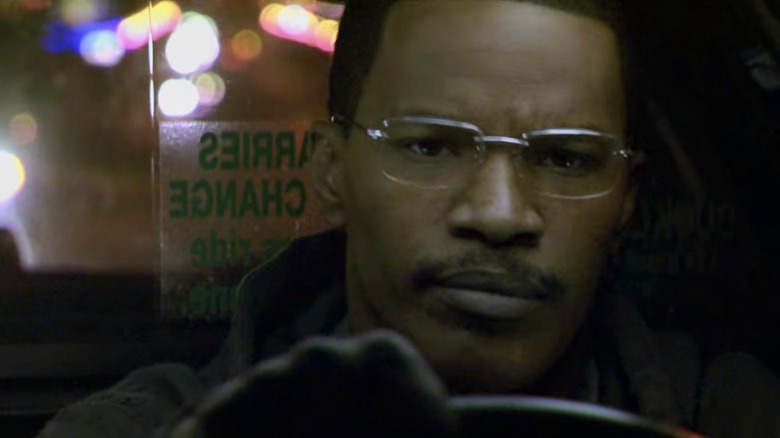

The surface-level plot of "Collateral" is easy enough to follow and describe in 25 words: hitman Vincent (Tom Cruise) forces cabbie Max (Jamie Foxx) to drive him around L.A. at night as he crosses off names on his kill list. Thematically, there's a lot more to the film than that.

Taken as a mere action thriller, the ending of "Collateral" might not need explaining, per se, but maybe it's worth reexamining with a deeper interpretation in mind. This is a movie with some meat on its bones where subtext is concerned. It emerges in the dialogue, the character roles, and the twists and turns of the plot: all of which go toward a metaphorical examination of the failure of the American dream for working-class individuals like Max, and the potential breakdown of the social order at the hands of morally grey-collared professionals like Vincent.

"Collateral" has two other key supporting characters: the federal prosecutor Annie (Jada Pinkett Smith) and the LAPD detective Ray (Mark Ruffalo). Annie and Ray represent law and order, which Vincent threatens with a resolve as steely as his suit and hair. Let's start the meter now — and do note the spoilers light on top of this yellow cab.

The dream of Island Limos

"Collateral" breaks into its third act with a car crash. After riding around with him all night, murdering people, Vincent has turned Max's whole life and worldview upside down, so Max returns the favor by running red lights and flipping the cab.

What pushes Max to his breaking point is a monologue Vincent delivers right before this, where he dismantles Max's dream of someday owning his own company, Island Limos. At the beginning of the movie, we saw how Max kept a postcard of a tropical island in the sun visor above his driver's seat. It's the classic image that an office worker might have on their wall calendar to inspire them through the doldrums of their job.

Max's office, as it were, just happens to be one on wheels. He was doing mobile work, or remote work, before it was in-fashion. Released in 2004, "Collateral" positions Max as the face of the century to come, someone whose job comes with no retirement or health benefits and whose boss is just a voice on the radio, all too ready to "extort a working man," as Vincent puts it.

Vincent suggests unionizing, but Max tells himself this job is temporary. The only problem is, he's been doing it for 12 years. This leaves him stuck in a routine where all he does is talk about his dream to other people. He develops a good rapport with Annie, so he's willing to share it with her and even give her the postcard, which leaves him with her business card in its place. However, with Vincent, Max is more guarded, perhaps because Vincent can see right through all of his dreamer-but-not-a-doer "bulls***."

'Nobody knows each other'

Foxx won the Oscar for Best Actor for his 2004 performance in "Ray" — a biopic where he had his eyes glued shut to play blind musician Ray Charles — but he also received a Best Supporting Actor nomination for his role that year as Max in "Collateral." In a lot of ways, Max is a more relatable character because he's an everyman, not a bonafide musical genius. The same could be said of one of Vincent's targets, a jazz club owner named Daniel (Barry Shabaka Henley), who met Miles Davis and had the night of his life jamming with him before he got drafted into the war and life happened, derailing his dream of being a musician.

To hear Max's mother Ida (Irma P. Hall) tell it, he's living his own dream already. She thinks he's got his limo company set up and drives famous people around because that's the image he lets her take from their interactions. "Max never had many friends," Ida reveals to Vincent in the hospital. "Always talking to his self in the mirror. It's unhealthy."

Though internet culture was not ubiquitous yet and the technology we see in "Collateral" is that of flip phones and flash drives, this side of Max's character somewhat anticipated the rise of social media and people's tendency to publicly curate their selves for an attentive audience that may or may not exist.

Speaking of the Greater Los Angeles area as a microcosm for the country, Max says, "17 million people ... and nobody knows each other." He sees the world changing and says, "We gotta make the best of it, improvise, adapt to the environment." Yet his idea of that is to coldly execute tasks and execute people.

The illusion of progress

Throughout "Collateral," we see Max getting in touch with his inner Vincent, reusing lines he's heard from Cruise's character to stand up for himself. Early on, when Vincent remarks to Max, "You're one of these guys that do instead of talk," there's a mocking edge to it, though, because we know that's not true about Max.

While waiting for the stars to align and everything to be "perfect," Max has become one of the plebeians Vincent describes who, after a decade-plus, is still stuck in the "same job, same place, same routine." Though he's always on the go, always moving, always working, Max is really just driving in circles around L.A., making no forward progress on his dream. This is what leads Vincent to finally dress him down before "Collateral" moves out of the two-man taxi, where Max chauffeurs him around, and into the mass transit system of the subway, where they're both passengers. To Max, it's a devastating personal takedown when Vincent says:

"Someday. Someday my dream will come. One night, you'll wake up and you'll discover it never happened. It's all turned around on you, and it never will. Suddenly, you are old. Didn't happen, and it never will. Because you were never going to do it, anyway. You'll push it into memory, then zone out in your BarcaLounger, being hypnotized by daytime TV for the rest of your life. Don't you talk to me about murder. All it ever took was a down payment on a Lincoln Town Car. Or that girl. You can't even call that girl. What the f*** are you still doing driving a cab?"

When success outstrips humanity

Described variously as a "badass sociopath" and "meat-eater super-assassin," Vincent represents the goal-oriented professional, driven to succeed no matter who he hurts. The last words out of his mouth before Max improbably outguns him at the end of "Collateral" are "I do this for a living."

Right up until the end, Vincent is laser-focused on his work, to the exclusion of all else, even basic human empathy. By his own admission, he's "indifferent" to the plight of others. As Max observes, Vincent lacks "the standard parts that are supposed to be there in people." He's a contract worker, a killer, who operates in the private sector and doesn't get any paid sick leave.

"I don't meet people," Vincent states. His current boss, Felix Reyes-Torrena (Javier Bardem), doesn't even know what he looks like. They've never had a face-to-face conversation, which allows Max to pose as Vincent and stand up to another boss who is ready to terminate his employee (in the Arnold Schwarzenegger sense of "terminate") the minute that employee brings a problem before him.

The problem is that Vincent has lost his list, all the intel on his targets, thanks to Max throwing it over the side of a pedestrian bridge onto the freeway. Since Vincent is just an independent contractor and not a real employee, Reyes-Torrena expects him to sort things out himself. "Sorry does not put Humpty Dumpty back together again."

Vincent's fate is foreshadowed early in "Collateral" with the anecdote he shares about a guy who died on the subway and rode around on it for six hours before anyone noticed. This comes right after he calls L.A. "too sprawled out, disconnected," a line where he could just as easily be talking about modern society in general.

Society and the individual

With his slicked-back hair and goatee, Ruffalo's character, Ray, almost seems like a cop out of another Mann movie — "Miami Vice," maybe. "Collateral" builds him up as a ray (ha) of hope, and you think he's going to come to the rescue, but instead, his death becomes the script's All Is Lost moment. To Vincent, a character motivated by success at the expense of human life, this guy with a badge barely registers. That's why he guns Ray down like he's nothing, as if to casually break the whole law in the form of one man.

What's one person's death weighed against Rwandan genocide and six billion people on the planet? This is the mentality Vincent brings with him into the U.S. Attorney's offices at the end of "Collateral." His presence there endangers the very fabric of society. Max can see the collapse playing out in real time; he's on the phone with Max's last surprise target, Annie, watching as Vincent comes for her through the windows. Only when Max steps up and the dreamer takes action is he able to forestall her death and his own.

The camera in "Collateral" often takes on a God's-eye view, looking straight down from the night sky at Max's cab as it moves through the streets. The law won't save the day down there; it's too easily broken. And as we see in "Collateral," beeping the horn for help only attracts the attention of muggers.

"Take comfort in knowing you never had a choice," Vincent tells him. Yet in the end, Max does have a choice. He can be the change he wants to see. In "Collateral," the responsibility of jumpstarting one's dream and preserving order falls not on outside forces or institutions, but on the individual.