Don't Worry Darling Cinematographer Matthew Libatique Brings The Light [Interview]

Cinematographer Matthew Libatique makes the sun turn from dreamy to nightmarish in "Don't Worry Darling." Olivia Wilde's film begins with a glow like a classic postcard, but it never feels quite right. Along the way, Wilde and Libatique turn up the heat in Alice's (Florence Pugh) world.

Libatique's name is no stranger to a film fan or anyone remotely familiar with cinematography. The two-time Academy Award nominee is a longtime collaborator of Darren Aronofsky and Spike Lee, plus he worked with the late Joel Schumacher several times. Most recently, he shot Aronofsky's "The Whale," "Birds of Prey," and "A Star is Born." We could've talked to Libatique all day long about his films. Recently, we mostly talked to him about his work on "Don't Worry Darling," his love-hate relationship with natural light, and of course, "Josie And the Pussycats."

'I have a love-hate relationship with natural light'

For "Don't Worry Darling," did you go back to a lot of mid-century photography? Like Slim Aarons or any names in particular to help create this world?

Yeah, Slim Aarons, of course, was a reference. He sort of has a signature photograph at the Kaufman house, which we shot at as a location. We were so tempted to recreate it, but resisted in all the other things we had to do those days. Certainly of the atmosphere, Slim Aarons, his photography was so much about capturing the essence of groups of people at a certain time. One of the goals of the film that Olivia had going in one of the first things she wanted to really establish with me is visually how we tell that. The notion that these people are in this idyllic yet debaucherous place where everybody's just living their best life.

The light feels intense in these houses, almost like dollhouses.

Oh, I think Palm Springs has that quality, and we were so fortunate. I feel fortunate to shoot at a time where the sun really could be a character, because it was low enough in the sky to create long shadows. It helped us bridge the gap between shooting those exterior locations in the cul-de-sac and our set, which we shot on a stage in Santa Corina. Using the sun as the glue between those two spaces, that was paramount, really. It just goes a long way to establish the visual or the atmospheric language in the movie.

What's your relationship with natural light these days? Do you know exactly what you have to do or can it still be very unpredictable?

It's definitely unpredictable. I have a love-hate relationship with natural light. You're bending time. You're bending time, you're bending light, you're using your skill set to be able to shoot things at a certain time. Something that takes three days to shoot feels like the five minutes that it takes up in the movie. With more experience, you learn that trying to create naturalism is far more difficult than actually just trying to go with it. My first go-to is actually trying to be clever about how to go about shooting an exterior or shooting at a location and at natural light at the optimum times, rather than force feed artificial light that sort of seems naturalistic.

People who are my references, a lot of photographers, they don't light, they find it. I try to keep that mentality as much as I can. Obviously, if it's an 11 shot scene then that's going to be harder to do. But yeah, the actual light that's occurring in the space is what I try to achieve. It's really about trying to figure out what time that is.

Say for the Busby Berkeley-esque dance sequences, do you have a love-hate relationship with artificial lighting as well?

That's another phase three of cinematography. Getting to know really what the director's references are. But then you're really giving birth to something out of nothing. Those are exciting opportunities, because things you're inspired by can come and shine through. This is one of those cases where the light was, it was also a vehicle, obviously a looming scene, but it's also a vehicle to sell the geometric shape of the dance choreography.

It was also used to exploit the artifacts of the lens. Many times the lights would be focused into the lens during performance. And those are visual ties to the film where we do the same thing and let the sun hit the lens, light hit the lens. And those aberrations in optics were kind of a theme to create imperfection in this world.

Do you enjoy creating imperfections?

Well, they were definitely moments that when they work narratively, they're definitely some of my favorite moments. They're beautiful, but you could easily overdo it. It's a fine line, I think. Of course it's good every time you're surprised you have a game plan going in, all of a sudden something happens and it's magical, then it creates more inspiration to continue forward. Putting yourself in the position with the right sort of strategy allows those mistakes to actually reap the benefits.

'It lived long enough to have relevance'

Like you said, those sequences are beautiful, but you can overdo it. How do you avoid overdoing it?

Well, I don't know. I haven't gotten to a place now where I've watched the film and don't critique the cinematography. The last time I saw it was in Venice and I was watching it and I'm in this amazing place and this amazing theater and with all these amazing people around me and I'm sitting there watching it, I'm color timing it. It's like, I should have done this, I should have done that. I'm trying to half the time telling myself to snap out of it. I guess I'd maybe have taken a flare or two away, I guess maybe not reached for one in a particular scene. I can't even identify which particular ones bother me, but I felt like I got the idea and maybe I should have done one less. You know what I mean? But that's just me being perhaps overly critical.

So when do you get to that point where you don't feel overly critical?

I'm re-timing "Pi." We took the original 16 millimeter positives, that was the negative because we shot reversal and we scanned it in 7K, and I've been re-timing it for a re-release. So I've distanced myself from that one enough. It takes a while. It has to live and breathe and become part of the ether for me to let go. This movie, though, hasn't been put out in the world yet. Hasn't really been born until it goes into theaters for people. I don't count this. I don't really count festivals. Festivals are just...

They are celebratory experiences.

They are celebratory experiences and you don't know who's telling you the truth. Who really likes it, who really hates it. And why do they really hate it? Do they hate it because of what somebody was wearing or did they hate it because they didn't like the film? So I wait until the film's release and it has its run. And then I think then I can sort of, okay, it is what it is and you get the general consensus.

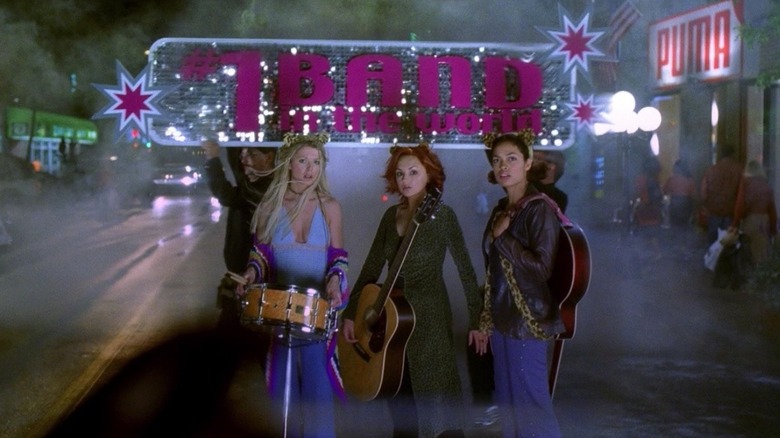

Sometimes the general consensus doesn't even come until later. "Josie And The Pussycats" is now recognized as a great movie, but at the time, it wasn't.

Oh, that's a great example now. Yeah, that's a really good one. I loved doing that film. It's funny, I ran into Deb Kaplan in Venice, one of the directors of that film, and we talked about that and how crazy it is that it's come full circle and it's happened to other films that weren't really well received at their time.

"The Fountain" comes to mind as well, and "Mother" comes to mind as well. But those films are all pretty loved by the people who like them. 've heard nothing but great things. "Josie" is a real surprise to me, but it's such a time capsule film about a time and pop culturally prophetic, in some ways, that it lived long enough to have relevance. It's really interesting. But as far as critiquing my work, I look at that, I can enjoy those. All three of those now.

When you were looking back at "Pi," did you think at all about the cinematographer you were then versus now?

Oh, absolutely. But the difference is that it's so long ago and I internally know that. I don't dwell on it. I'm not that person anymore. And I didn't even think about it, I thought about for a brief moment, what choices would I have made now? And it's not even worth it. I'm perfectly happy enjoying the choices that I made, whether they were right or wrong because the movie just had its own life. I'm just being brought in. I don't know, I just feel like maybe an uncle or something coming back to say hello to somebody you haven't seen in 25 years. "Wow. You're really grown up." That type of thing.

'How much sugar did we pour in the coffee before it ceases to be coffee?'

Even with all your experience, you still chase uncertainty to grow, as you've put it. For "Don't Worry Darling," what were moments of uncertainty you grew from?

There's intention. Meeting Olivia, she's so inspiring visually. It's important to her what the cinematography is. It's important to her what the palette is that she weighs in on production design and costume and design hair and makeup equally. With the camera and the light, the uncertainty was really how bold we want it to be.

Going back to what I was saying before, it is that fine line. How much sugar did we pour in the coffee before it ceases to be coffee? And so, that was a little bit of anxiety. And frankly, we didn't have a second unit for the action scene in the third act. She was so excited about shooting this sequence and as a cinematographer, I didn't want it to fail. We worked so hard to build this world that this third action sequence was the climax of the film.

You see how the film ends and it ends as a punctuation to this sequence, this travel from the cul-de-sac to the headquarters. I'm not a second unit director, and Olivia isn't really an action director either, but we did our due diligence. We did the research. We just compiled a bunch of sequences and started to pick apart things that we liked. That was the biggest, not hurdle, but was the biggest concern for me. It's like, okay, so many times you just don't want the third act disappointing on a film. It's meant to keep people in their seats and have them eating the last bit of popcorn. We just wanted to make sure that we would service that. I think it does.

I'm proud of that sequence, but that was the most anxiety I had about the film. We worked on the sequence as we were shooting because of course, when we started shooting, we weren't ready to shoot that sequence. Luckily, we shot at the end of the schedule, but we storyboarded it. Then the budget had to cut it back and then had to rework sequences. And so, we just kept working on it and working on it, knowing when we both had the same goal, she said to me, "I just want a bad*ss action sequence." That's a good direction. For me, okay, do I have the right gear? Do I have the right tools? I get all the right tools in place and don't waste the thing because we didn't have the budget to overdo it. But I think it worked out.

There are experiences from your past, such as shooting music videos, I imagined helped with those surreal dance sequences and even Harry Styles' dance in the film. Did you draw from those past jobs in thinking of the best way to capture and shoot dancing?

Oh, it's funny. Yes and no. I always think about when I was doing music videos, I realized that a 35 millimeter was my favorite lens on shooting the drummer. For example, when Harry's doing barrel rolls on the stage. Okay, what's the 35 millimeter for the drummer for this sequence? Really, it's finding the lens that sort of captures that. Not too wide, not too tight.

What's the proper lens that gets the feeling of what he is doing, because he's really doing those barrel rolls. And it's like, why is this man being made to do this by this other guy? To answer the questions, sure, that was a lot of experience. I cut my teeth with that. A lot of cinematographers a generation before me cut their teeth in documentaries. I was fortunate enough to do music videos.

'Why put a hat on a hat?'

Mirrors and reflections are key visuals in "Don't Worry Darling." Was "Black Swan" another experience that helped you there?

Definitely. Just working with mirrors and reflections, how do you make the notion of them new? And I don't know that you make them new. I think you make those moments count. So are they well placed? There's that moment where she's in the ballet, speaking of "Black Swan," but she's in the ballet studio and then she sees herself as Kiki's character, Margaret. And that was very much out of the idea of "Black Swan."

In fact, the visual effects person that worked on the film is the same person as "Black Swan." And we could reference things we had done before to each other when we shot that. But then some of the reflections and some of the, maybe shooting through glass at Florence's character or Alice inside the bathroom, for example, in her house, all those things are obviously influenced by other movies that use reflection. It's the placement of them that is everything. But technically these days, we're not afraid to lean on our friends in visual effects to put the camera in a better place.

The use of light reflecting off the saran wrap around Alice's face, that's very unsettling.

Oh that, yeah. Well, the house had so many opportunities to light from. In fact there was light coming from every direction that it created specular highlights in the plastic. So as it was wrapping around, we could have even explored that more, but I felt why put a hat on a hat? It was pretty wild what she was doing.

Another effective shot is Alice in the kitchen and Frank (Chris Pine), standing behind her out of focus. He's not moving much, but it's unsettling.

It's interesting you said that, I love that shot too. It is so simple. It's an old technique that's been used and used and used, but you know you can do it again. What's it conveying? I love that shot. Chris could act out of focus. He just stands there. He's doing something and you're feeling it even though he stopped. I think that we had a lot of moments like that.

Going back to the reflection thing too, when Alice goes into the bathroom during that victory celebration while Jack is dancing on the stage and being presented his ring and Bunny goes in to talk to her, that was a nightmare. I don't know how many times we had to pan our camera out. We definitely had to, because at a certain point there were just too many options in that place. And it was chosen, Olivia chose that and [screenwriter] Katie [Silberman] chose that because it was a climax in her dissension.

A cinematographer recently told me what she really appreciates about your work are your close-ups. For you, what makes for a great close-up?

It's the tone of the scene. I'd say over the years, it's not always in the same place. Sometimes the close-up is just literally a single and sometimes you need to see the person's chest and you need to see their shoulders move because they're physical. And sometimes the close-up is like, there's no hairline and you're deciding between their eyes and their chin.

I think it's different for the movie and this moment and really where you put the camera is where you're placing the audience. So how close do you want the audience? Proximity is everything. Sometimes that proximity should be consistent like in "Mother!" or "A Star Is Born." And sometimes that proximity should change. I think in "Don't Worry Darling" it changes a little bit, because Alice has so many moments where she's by herself, that subjectivity didn't have to be in a closeup. It could also be in a wide, like when she's vacuuming. The apartment because you revisit that moment twice, when she's cleaning the house. You revisit that two or three times, she's making breakfast, it doesn't always have to be the same shot.

So there's a little more variety in "Don't Worry Darling," when it comes to it. And getting a close-up really to me is conveying a bunch of different things. Obviously, you're putting a camera there and you're cutting to it for emotional value or something that's being said that you want to make a point of, but honestly, the same power could be done with something a bit wider. So when you say close up, I think it speaks to the idea of putting the camera in the right place, if that makes sense.

"Don't Worry Darling" is now playing in theaters.