How Top Gun Set The Stage For A Military Coup In The Movie Business

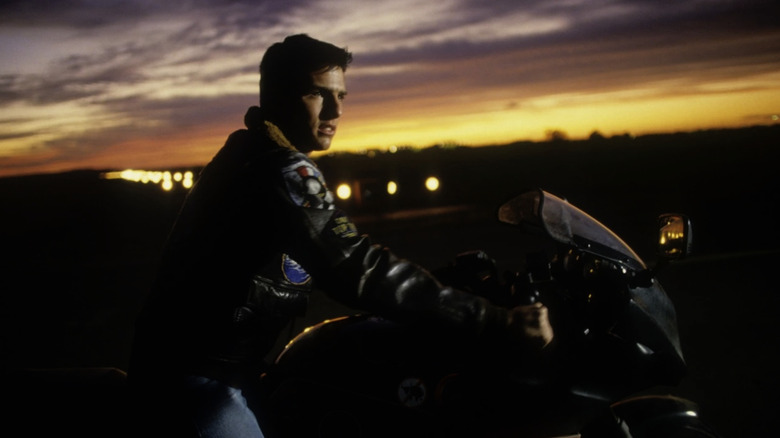

In 1986, Tony Scott's "Top Gun" was the highest-grossing film of the year. Audiences flocked to see its newest movie star Tom Cruise, fresh off of "Risky Business" and "The Outsiders," frolic around a sun-kissed dreamscape of Coronado, California. Military recruitment booths were set up outside theaters, and naval aviator applications skyrocketed. With no active war and the scars of Vietnam slowly fading away with the younger generation, many young men wanted a taste of the glamorous and sexy pilot's life portrayed on screen.

It is 2022, and "Top Gun: Maverick" hit past the 1 billion mark at the worldwide box office. Time is a circle. There's a lot to unpack about how the film industry has changed in the 36 years in between these two films, but the success of "Maverick" exposes a few constants. One, Tom Cruise is still one of the biggest stars in Hollywood, a sentiment universally shared by many film enthusiasts. Two, the Pentagon's shadowed influence on blockbuster filmmaking persists to this day.

Yes, the relationship between Hollywood and the Pentagon has existed long before "Top Gun," in fact, the first-ever Academy Award for Best Picture was given to "Wings," which was created with oversight by the War Department. But while previous collaborations were deliberately political to motivate a current war effort, "Top Gun's" place in history feels like more of an attempt to rehabilitate the military's image in a new era of Reagan patriotism, and the mold of how the film was conceived would set a precedent for future blockbusters.

Top Gun set a precedent by working with the D.O.D. for all future blockbusters

Funding a movie that involves military-grade vehicles, weapons, and other equipment is an expensive endeavor for producers, especially if realism and authenticity is a goal for the filmmakers. When it came to "Top Gun" in particular, this involved dozens of jets, four aircraft carriers at sea, and permitted filming of the entire Miramar Naval Air Station near San Diego. According to a 1986 report from Time Magazine, the producers of the film paid $1.8 million for authorization of these assets directly from the Pentagon, as finding substitutes or trying to craft these resources would be so costly that the film wouldn't have been made.

The cost of military assets, however, proves to be higher than just financial value. When filmmakers agree to directly borrow resources from the Pentagon, there is also an agreement that the Pentagon is allowed creative input in how they are portrayed in each respective film, directly signing off on screenplays. This is where the Department of Defense and its public affairs officers come into play, and there are entire offices dedicated to different armed forces and their respective collaborations with Hollywood. Though the D.O.D. claims to mostly check for accuracy and withdrawal of sensitive information, it's not a huge leap that there would be a bias towards films that frame the military in a positive light.

Hollywood collaboration with the Pentagon has become more normalized

Time Magazine mentions Taylor Hackford's "An Officer and a Gentleman" as an example of a rejected film, characteristically because of its "rough language, steamy sex and, to the military mind, inaccurate view of boot camp." One more famous example is Francis Ford Coppola's "Apocalypse Now," which was rejected by Army Major Ray Smith on the false claim that "The army does not lend officers to the CIA to execute or murder other army officers." Coppola was forced to shoot the film in the Philippines after the lack of support, the D.O.D. poignantly passing on one of our greatest anti-war epics to grace cinemas.

In the present, Hollywood's involvement with the Pentagon has become increasingly normalized. Initially, the focus was mostly on war dramas such as "The Hurt Locker," but now this influence extends to genre pop culture juggernauts like the Marvel Cinematic Universe. There are a handful of foundational MCU entries that explicitly collaborated with the D.O.D. such as "Iron Man," "Iron Man 2," "Captain America: The First Avenger," "Captain America: The Winter Soldier," and most recently, "Captain Marvel" (Which even takes visual cues from "Top Gun" itself). Even extending past these explicit films, these adaptations of the colorful and magical Marvel universe have been aesthetically rooted in the language of science and military tech to strike a consistent tone with these early entries in the universe.

Top Gun Maverick's universal success parallels the original

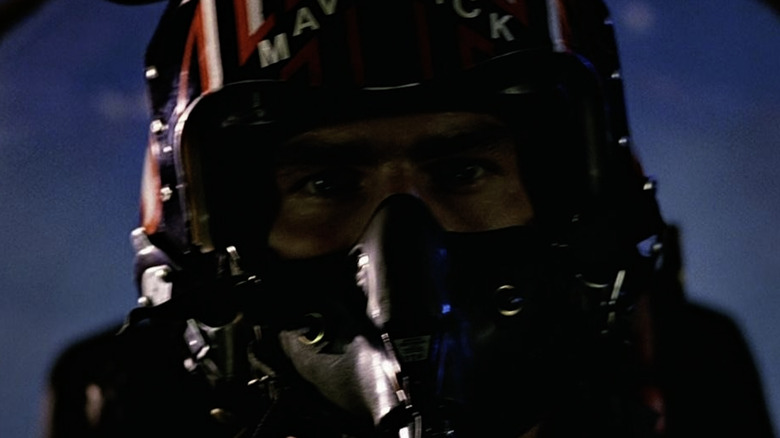

Rightfully, there have been many criticisms about the MCU and its subtextual fetishization of military aesthetics and ideals, especially as these are escapist family-friendly films aimed at children at the end of the day. This is what makes the universal success and critical praise of "Top Gun: Maverick" particularly interesting, as it is a full circle return to the grandiose and shiny portrayal of the naval air force that made the original "Top Gun" such a success.

Today's audiences are fully accepting "Top Gun" now just as they were in 1986. But what exactly motivates this love for Maverick? Is it a hunger for the type of engaging, star-studded action blockbuster it is? Is there enough nostalgia for the original to sustain its comeback? Do mainstream audiences care about the Pentagon's motivations in bolstering a film like this? What does the second life of "Top Gun" say about our current cultural climate? It's hard to tell while we're living in the current moment, unable to zoom out, but two things are for certain. One, the impact of the original film on Hollywood continues to this day. Two, Tom Cruise will be on our cinema screens for as long as he lives.