Tales From The Box Office: How Kevin Smith's Clerks Became The Little Movie That Could

Independent movies have been a thing for just about as long as movies have been a popular form of entertainment. But there was a point in the '90s when major studios realized that indie movies could also be good business, and Miramax was at the cutting edge of that movement, acquiring a string of films out of the festival circuit and turning them into hits. Miramax, founded by Bob Weinstein and the since-disgraced Harvey Weinstein (who is currently in prison), was so successful that Disney ended up buying the company in 1993.

Miramax wanted to prove that it could still do what it had always done despite being owned by the Mouse House. So, in 1994, the studio went to Sundance and went on a spending spree. Most notably, it acquired Quentin Tarantino's all-time classic "Pulp Fiction," which went on to become a gigantic hit and perhaps one of the most beloved movies of the decade overall. But that same year, the studio also set its sights on a buzzy little black and white title from a first-time filmmaker named Kevin Smith.

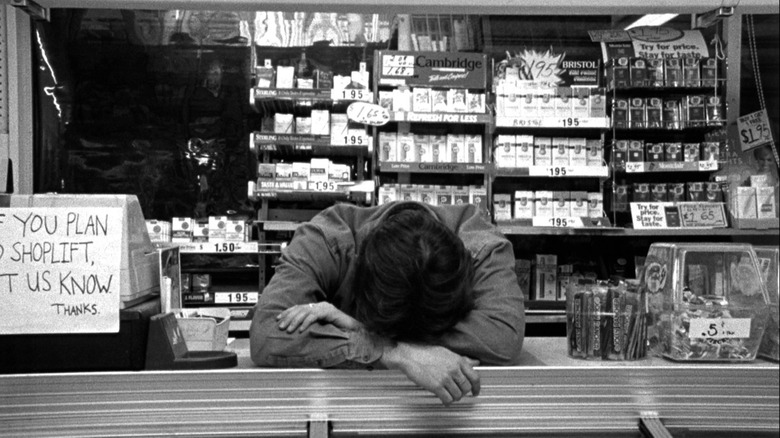

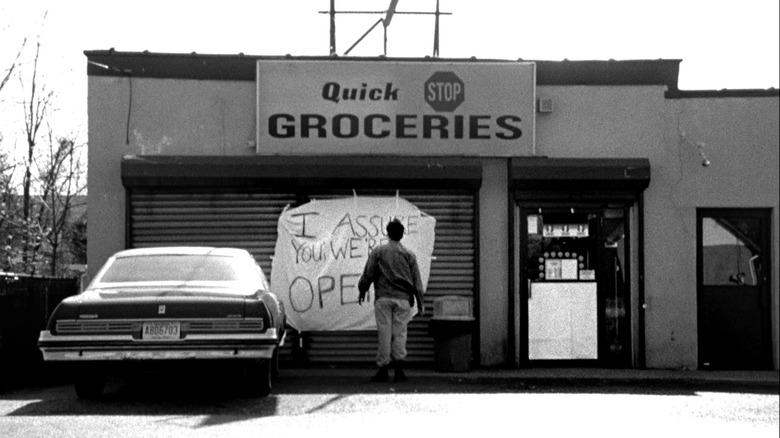

The unassuming, charming, and gritty little comedy about a couple of guys working at a convenience store/video store was "Clerks," and it became a success story the likes of which simply doesn't come around all that often. A little movie made for next to nothing with few resources in the middle of New Jersey launched a career that is still going to do this day and, amazingly enough, inspired an entire cinematic universe.

In honor of the release of "Clerks III," we're looking back at the original "Clerks," how it came to be, how it turned into a cult success story, and what lessons can be learned from it nearly 30 years later. Let's dig in, shall we?

The movie: Clerks

The story of "Clerks" is one that has been told many, many times, primarily by Kevin Smith himself. The man has never had anything but love for his debut feature film and is perfectly happy to talk about it nearly three decades removed from its original release. But the tale of this film is one that still holds water, particularly in a world where its success seems almost alien in the modern marketplace. How is that a movie that made less than $4 million could be considered such a success? It's all relative, dear reader.

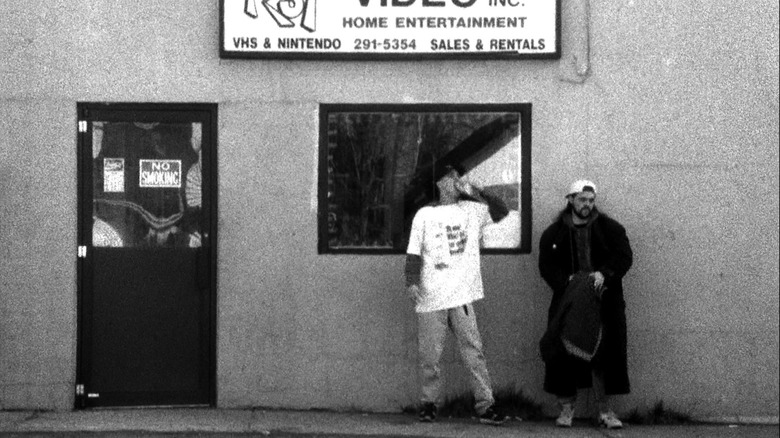

Smith has always cited Richard Linklater's "Slacker" as the movie that made him believe movie making was possible. Ultimately, Smith dropped out of the Vancouver Film School after just four months to, instead, make his very own movie. In the spirit of writing what you know, Smith decided to write a comedy about working at a convenience store, as that is what he knew from his own job at the time. And so, he sought to tell the tale of two underachievers named Dante (Brian O'Halloran) and Randall (Jeff Anderson) as they go about their day working at the Quick Stop, as well as the adjoining video store.

The budding filmmaker wrote the script in 1992 and whittled it down so that it might be something they could actually film on a microbudget. The lean crew consisted of Smith, his pal Scott Mosier (co-producer, coeditor), David Klein (the director of photography), and Ed Hapstack (camera assistant). While others contributed, this was the core team that banded together to make a movie on a shoestring budget.

Maxing out to chase the dream

Smith didn't come from money and had to get creative (perhaps recklessly so) to get the money together. To raise the $27,000, Smith used some of the money he had saved up for school that was leftover, profits from selling his comic book collection, as well as his paychecks from working at the real-life Quick Stop and RST Video. But the bulk of the funds came from maxing out ten different credit cards, meaning that Smith was going to be in serious debt to make his dream come to life.

Because the budget was so tight, Smith opted to shoot in black and white as it made lighting easier and more efficient. But that also, as a happy accident, gave the movie a distinctive look that helped it to stand out when the time came to show it to the world. Quick Stop agreed to let Smith film at the store, but it could only be filmed at night so as to not interrupt operations. So Smith and the crew filmed at night, while he would work his regular job during the day. Three weeks worth of night shoots in 1993 is what it took to get "Clerks" in the can.

Despite not having made a film before, Smith's determination and arguably foolish confidence got the job done, with the help of some of his many close friends — including Jason Mewes, who appears alongside him as Jay, the counterpart to Silent Bob. That determination and those maxed out credit cards were going to pay off in a big way come 1994.

The financial journey

"Clerks" debuted to the world at the Sundance Film Festival in 1994 following a screening for the Independent Feature Film Market — a screening that Bob Hawk, a member of the Sundance Advisory Committee, attended. Following its buzzy premiere at Sundance, Miramax swooped in to scoop up the rights to Smith's debut feature, paying a cool $227,000 for it, or just about ten times what it cost to make the movie in the first place. For the cast and crew, an instant success. But Miramax would soon discover this to be a worthwhile investment, to say the least.

The film garnered rave reviews at the time and was released in the U.S. in October of '94. In the true spirit of independent cinema, the film never played on more than 50 screens in the country, and yet it managed to find a great deal of success. "Clerks" generated more than $3 million at the domestic box office, coupled with a little more than $800,000 internationally. That means, a movie that cost a mere $27,000 to make earned more than 144 times that in ticket sales.

But that was truly just the tip of the iceberg. "Clerks" truly found its legs in the home video market and, while exact figures are not known, it is said to have generated tens of millions on VHS alone. Not to mention its various DVD and Blu-ray releases over the years. That made this a ridiculously wise investment for Miramax and, moreover, paved the way for Smith to have a career that was largely defined by less-is-more. Movies like "Chasing Amy," "Dogma," and "Clerks II" would find success as part of what Smith called the View Askewniverse, named for his production company View Askew. Yes, Smith was doing the whole cinematic universe thing before Marvel made it cool. Though, funnily enough, Smith credits Marvel Comics for the idea, as they had been doing it in the comics for decades before bringing the concept to the silver screen.

The lessons contained within

There is much to extract from the success of "Clerks" looking back but, from a studio perspective, it really is worth ruminating on the relativity of success. Movie budgets have only inflated increasingly in the aftermath of the pandemic and, when a budget increases, it's harder to have that movie become a success. It's simple dollars and cents. While this is an extreme example, it would be nice to see more micro-budget stuff get a fair shake, rather than just dumped directly to Redbox or have them languish in the bottomless pit of hardly-advertised stuff that exists in the land of VOD.

To me, the bigger takeaway here is more individual and more inspirational. Sure, one can say what they will of some of Smith's films like "Yoga Hosers" or "Jersey Girl," which may be easy targets. But I would argue that this movie's success and the career that it gave a kid from New Jersey is evidence that just about anyone can do almost anything with the right amount of determination. This is not limited to filmmaking. The success of this film should only serve to inspire people, in my humble opinion.

Beyond that, it's admirable that Smith has largely maintained a similar sense of fiscal responsibility throughout his career. Heck, "Clerks III" literally got made because "Jay and Silent Bob Reboot" sold so many Blu-rays. In this day and age, that's remarkable, but only possible because Smith isn't overextending. He's making movies for his audience and for a price that doesn't put too much risk into the equation. This all circles back to what Smith said back in 1994, just as his journey was beginning: "There is so little risk involved. You don't have to please anybody but yourself." In this case, it just helps that the resulting film became a beloved '90s classic.