Jean-Luc Godard's Contempt Reveals All That Is Possible With Cinema

My favorite tracking shot in film history is not a tracking shot. It's a shot of a tracking shot.

The scene in question opens Jean Luc-Godard's "Contempt," and, visually, consists of little more than a movie camera gliding down a dolly track toward a stationary camera, which serves as the audience's POV. As the camera moves closer into view, we see that it is shooting, at a 90-degree angle square to our perspective, a young woman (Giorgia Moll) scribbling notations in a book. Eventually, the camera rolls to a stop directly in front of our camera, which is now a low-angle shot of the film's cinematographer, Raoul Coutard, who pans his implement 90-degrees before pointing it downward at the audience. The effect is at once startling and amusing. We have, in essence, locked eyes with the filmmaker.

This may not sound terribly thrilling in writing, but factor in a narrator intoning the credits of the film sans onscreen text, and, most crucially, Georges Delerue's lushly orchestrated theme, and you can't help but feel that a work of epic significance is about to unfold.

"Contempt" is Godard's masterpiece in that, over the next 100 minutes, it surpasses the audience's expectations by completely subverting them. The movie was sold as Godard's first big-budget motion picture, a romantic, CinemaScope tragedy set against a troubled production of Homer's "Odyssey." Godard, who died Tuesday at the age of 91, delivers on this promise, but in the same meta-referential manner that made him the enfant terrible of the French New Wave. It's emotionally distant, yet deeply personal — a film of tremendous beauty filled with movie quotations both spoken and shown. It's the gateway to and, for many, the hasty exit from Godard's brilliantly perplexing oeuvre.

For me, it was the moment everything film professors had clumsily force fed me in college finally made sense.

Breathless praise

Of the French New Wave filmmakers (a distinguished roster of revolutionaries that included François Truffaut, Jacques Rivette, Agnes Varda, and Éric Rohmer), Godard was easily the brattiest. He argued endlessly with his colleagues, stole money to get his films made and, later in life, disparaged the work of popular filmmakers like Steven Spielberg (he once claimed he could prove via a frame-by-frame analysis of the director's films that he is a lousy artist).

As a young cinephile, I knew enough to be respectful of Godard's impact on the medium, but not enough to vibe on what he was up to formally with his debut feature "Breathless." I saw the allusions to Bogart and Cagney, but I didn't feel them. Once Jean-Paul Belmondo and Jean Seberg launched into their seemingly endless lovers' quarrel at the midpoint of the movie, I felt only exhaustion. In college, I was exposed to some of Godard's visual essays with the Dziga-Vertov collective, and, in the early 1990s, their discursive didacticism landed like self-parody.

As I fell in love with Truffaut's straightforward genre experimentation and Claude Chabrol's fine-tuned thrillers, I decided to leave Godard to the try-hard revolutionaries sporting Che Guevara t-shirts. Godard could jump-cut himself to Poughkeepsie for all I cared. He was clearly not for me.

A renewed Contempt

It used to be something of a New York City summer tradition for an underseen or previously written-off classic to get a loving restoration and a theatrical run at one of the top repertory houses. In 1996, my first year in Manhattan, that honor went to René Clément's "Purple Noon," which sent me scurrying to the Strand to snatch up as much Patricia Highsmith as I could afford. In 1997, the big revival was Godard's "Contempt," which I viewed skeptically until I saw the trailer before a screening at the Lincoln Plaza Cinemas.

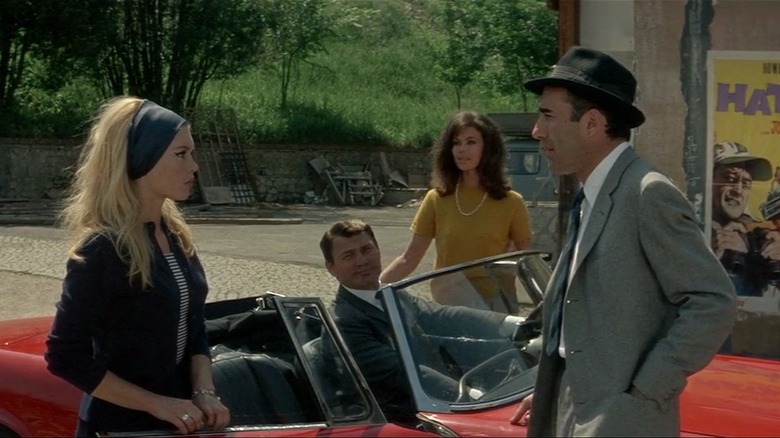

Personally cut by Godard, the trailer for "Contempt" is a work of art in itself. Coutard's resplendent CinemaScope cinematography is intercut with multicolored titles, while a male and female narrator exuberantly describe the basic elements of the film: Paul (Michel Piccoli), a slumming screenwriter, has accepted a lucrative opportunity to rewrite a huge movie, and has ill-advisedly brought his girlfriend, Camille (Brigette Bardot), along for the ride. I was blown away. I knew of the film's notoriety (particularly that producer Carlo Ponti had insisted on reshoots wherein the recalcitrant filmmaker was forced to show off Bardot's bare derrière), but it was Godard and it was incredibly hard to track down on VHS, so I'd ignored it.

There was little chance I was going to miss "Contempt" during its summer run regardless because I lived in NYC's cinemas back then, but that trailer was the first time Godard had moved me to do more than press the stop button on my VCR. Maybe this was the one.

The hero's journey is not the only journey

There are three pivotal moments in my life as a film lover, and they are all first-time viewings: "Jaws" on Betamax at the age of five, "The Untouchables" at a Naples, Florida theater at 13, and "Contempt" at the Lincoln Plaza Cinemas at 23.

Throughout most of college, I'd had Joseph Campbell's hero's journey drilled into my creative consciousness. My playwriting mentor preached the gospel of "Jaws," a church to which I'd belonged since my primary mode of transport was a Big Wheel. Though my taste in movies had grown a tad more sophisticated since then (a maturation obnoxiously signified by the posters for Krzysztof Kieślowski's "Three Colors" trilogy that adorned the slanted ceiling of my converted-attic, senior-year bedroom), I craved classicism.

The opening of "Contempt" changed everything. It wasn't terribly outré. The spoken credits device had been utilized by Robert Altman at the end of "M*A*S*H," and, as a Brian De Palma devotee, I was well acclimated to tracking shots that called attention to themselves. But the fourth-wall shattering movement of Coutard's camera, backed by that heightened Delerue cue, was shockingly lyrical. And that last bit of narration before Godard cuts into the film slashed to the core of my being: "'The cinema,' said Andre Bazin, 'substitutes for our gaze a world more in harmony with our desires.' Contempt is a story of that world."

A diary of hate

"Contempt" was not a new story. Fatalistic films about compromised screenwriters like "In a Lonely Place" and "Sunset Boulevard" had presaged it, and, given Godard's stated admiration for the director of the former ("Cinema is Nicholas Ray"), it's safe to assume the young French filmmaker used it as a reference point. But Godard isn't telling some other artist's tale of woe. This is his. He hated his producers (Ponti and Joseph E. Levine), and turned Jack Palance's bloviating bully, Jeremy Prokosch, into a hideous amalgamation of the two. Prokosch berates the director of "The Odyssey" (Fritz Lang playing himself) for having made unreleasable dreck (which, judging from the dailies screened for Paul, he has), while making a brazen play for his newly hired writer's girlfriend. During one tantrum, he picks up a film reel and hurls it like a discus athlete. No one, not even Lang, lifts a voice of protest. It's not worth it. Their jobs depend on their obeisance.

Godard works his animosity for the gig into the dialogue as well. His distaste for being forced to shoot in CinemaScope results in one of the film's best lines, delivered by Lang: "It wasn't made for people. It's only good for snakes and funerals." He also revisits the divisive set-to between Belmondo and Seberg from "Breathless" with a strenuously protracted Piccoli-Bardot squabble that kicks off with a nod to Vincente Minnelli's "Some Came Running" before ending in unresolvable acrimony. This is knee-deep film nerdery, but it draws blood if you know the references.

The end crawl

The last third of "Contempt" takes place at the resplendent Casa Malaparte on the isle of Capri. As has been Godard's penchant throughout the film, the idyllic location is profaned by the ugliness of the characters' jealousies. Prokosch closes his conquest of Camille, at which point he whisks her away for a joyride in his sports car that kills them both. Godard does not show the wreck, only the wreckage, which is composed like a crime scene photograph. It's a stylistically practical decision (Godard wasn't exactly John Frankenheimer when it came to vehicular stunt work), and a haunting one. A minute ago they were alive, now they are gone. And because we've been viewing the film from Paul's aggrieved perspective, we feel little in the way of remorse. In the end, Paul leaves the production, while Lang continues to shoot. The show, however contaminated and devoid of artistic value, must go on.

Godard never made a film on this scale again. He loved analyzing the works of Howard Hawks and Alfred Hitchcock, but he didn't want to emulate them. He was too scatterbrained for that. He lacked their rugged temperament and focus. Godard subsumed cinema and altered the vocabulary, creating a language all his own that's indecipherable to people who can't chop it up about Anthony Mann Westerns until sunrise.

Godard loved to proclaim the death of cinema. He filmed his first eulogy with "Week-end" in 1967, and buried the medium many more times over the course of his career, before and after he completed his quixotic, four-and-a-half hour essay/documentary "Histoire(s) du cinema" in 1998. I've never really reckoned with his entire career because I thought he'd last forever, not out of contempt but for love of those flickering frames that makes life worth living.