'You Were Never Really Here' Is A Brilliant Movie Because Of What It Doesn't Show Us

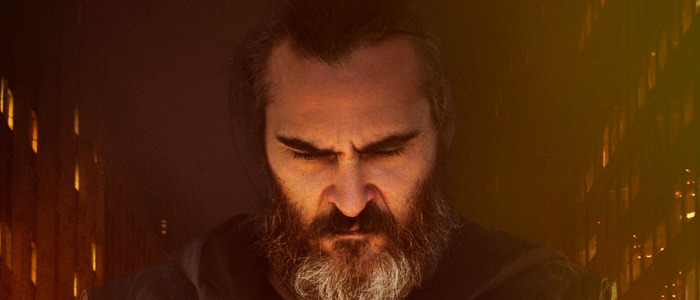

(In our Spoiler Reviews, we take a deep dive into a new release and get to the heart of what makes it tick...and every story point is up for discussion. In this entry: Lynne Ramsay's You Were Never Really Here.)There's a lot going on in Lynne Ramsay's You Were Never Really Here, and we see almost none of it. And yet, we still see everything we need to see. With a shockingly sparse presentation, Ramsay has concocted a lean, mean movie that skimps on specifics yet still packs a wallop. It's one of the most remarkable examples of less-is-more storytelling in recent memory.Spoilers for You Were Never Really Here follow.Joe is a troubled man. He has a very specific set of skills, and he uses them to great advantage. He lumbers through New York City like a some rough beast, all coiled muscles and clenched fists. He's not in great shape, yet he's imposing. He has a presence. He enters a room, and the thermostat drops; the tension mounts. One look at his pulled-back hair and unkempt beard and it's clear: something violent is going to happen.Something violent does happen in Lynne Ramsay's brutal, brilliant You Were Never Really Here. In fact, several violent things happen throughout the course of the film – and yet we see almost none of them. They exist just out of our line of sight – we catch the tail end of them, as the camera cuts to the few seconds after the violence has happened, just as the bodies are about to slam into the floor.This is part of what makes You Were Never Really Here tick, and it speaks to the nature of Ramsay's fine-tuned machine of a film. There's not an ounce of fat on You Were Never Really Here. At 90 minutes, Ramsay's films coasts along smoothly, pulling Joaquin Phoenix's Joe from one unsettling situation to the next. The story will occasionally pause for reflection – there's a lengthy, beautiful, heart breaking, and dialogue-free sequence where Joe has to dispose of the body of his dead mother – but the narrative never stumbles. Ramsay doesn't give it any room to stumble.There are many things that make You Were Never Really Here one of the best films of the year. The primary element is Phoenix, who delivers yet another engrossing, fully formed performance to remind us all there's no other actor like him working right now. But what really makes You Were Never Really Here sing is how startlingly lean the movie is. Ramsay and editor Joe Bini have cut the film down to its bare bones. There are times when it feels as if huge chunks of plot have been surgically excised from the film. And yet, You Were Never Really Here never suffers because of this. This isn't some hack-job – a film chopped up by the studio in desperate attempt to salvage something disastrous. Instead, this is the stunning design of You Were Never Really Here. Here, less is more. Hell, here, less is everything.

Violence Without Violence

The story, adapted from the novella by Jonathan Ames, has shades of The Searchers; shades of Taxi Driver; shades of Clean, Shaven; shades of even Ghost Dog: The Way of the Samurai. Joe makes his living saving missing children while dolling out bursts of violence. Before a job, he purchases a hammer, stalks his prey, waits endless hours, and then acts. He has no qualms about killing; he brings his hammer down onto the skull of anyone in his way in an almost casual manner.Ames's novella gives us some background – Joe is both a former soldier and a former FBI agent there. But Ramsay is more abstract in her approach. The cut of the film that played at Cannes had a few more flashbacks to Joe's life as a soldier, but the film as it exists now treats Joe's past almost like a dream. There are flashes of Joe's military time – filmed in extreme close-ups, with shots of sand, and sun, and ever-looming death. The seemingly charitable act of handing over a candy bar to a child results in a sudden burst of violence. These are haunting, haunted images – for Joe, and for us.Joe's latest job involves rescuing a politician's underage daughter (Ekaterina Samsonov). She's been stashed away in an ordinary-looking brownstone which doubles as a brothel for underage girls. To Joe, this is just another job. It starts off without a hitch – Joe moves from one corner of the brownstone to the next, putting his hammer to use. Ramsay shoots this through CCTV footage – security cams are all over the house, and they're capturing Joe at work. It's here where it becomes clear that despite You Were Never Really Here's inherently violent nature, Ramsay's approach to the violence is deliberately restrained."There was a decision not to show the violence," said editor Joe Bini. "At first, the screenplay was pretty graphically violent, and it became more and more clear that this was not the way we would want it to go." This isn't Ramsay playing it safe – this is Ramsay denying a certain catharsis. Because, deep down, we want Joe to hurt the people he hurts. And yet, Ramsay keeps it always just out of frame. She wants us to question that bloodlust; to turn it inward, and ask just what it is we're looking for here. At the same time, not showing the violence somehow makes it all the more brutal. Without witnessing the bloody acts, we're forced to conjure them up in our minds. We're witnessing violence without violence. Joe rescues the girl, named Nina, and that's when things start to go very wrong. Nina's father turns up dead – an apparent suicide. Corrupt cops show up, steal the girl away, and nearly kill Joe. From here, Joe has a choice – he can walk away, or he can track down whomever has Nina, and make them suffer. You can probably guess which option he picks.

No Catharsis

In the studio version of this film, there would be more time devoted to both Joe's search for the missing girl, and his plans for revenge. Joe would be methodical, and we'd get to see every detail of his plan down to the letter. He might even have some sort of sidekick character – someone he can talk to and bounce ideas (and plot details) off of. We might have even been saddled with a voice over narration, as Joe talks us through his uneasy mind.But Ramsay doesn't go for any of that. Instead, she dishes out only the bare minimum. And yet, we know everything we need to know. We know Joe is troubled because Bini's editing, the cinematography from Thomas Townend, and, most important of all, the sound design courtesy of Paul Davies, gives us all the insight into Joe we need. We're seeing a good portion of the film through Joe's eyes, and as a result, the world looks and sounds harsh – bursts of blinding light coupled with a monstrous roaring noise. It's the sound of the city, but it's also the sound of some sort of rough, abysmal tide crashing somewhere within Joe's head. Davies' sound design filters in breaking glass, jarring screeches, and the noise of Phoenix muttering unintelligibly to himself. Nothing is really being said with all this, yet we're being given a full picture of Joe as a result.The most surprising use of Ramsay's sparse storytelling method comes near the conclusion of You Were Never Really Here. Joe has finally tracked down the man who is holding the girl prisoner. The man who has orchestrated all of the pain and suffering that's befallen Joe for most of the movie. Like the missing girl's father, this man is also a politician – a governor, played by Alessandro Nivola. This character is, in a sense, the film's main antagonist. The bad guy whom Joe has to now face off against. And what do we learn about this character?Nothing.In fact, Nivola doesn't even have a single line in the film. Yet again, Ramsay and editor Joe Bini are telling us everything we need to know about this character – and we can tell without ever hearing a word he says that he's vile. Ramsay introduces him through a long POV shot – we're in Joe's headspace, watching as the Governor strolls from his campaign headquarters, flanked by armed guards. Just the way Nivola carries himself, cocksure and smug, is enough to make your bile rise.Later, Ramsay shows Nivola's character delicately fingering photos of his captive when she was even younger. It's a repulsive, silent sequence – we're told that Nina is his "favorite" of the numerous underage girls he's sexually abused, and she apparently has been for quite some time, even when she was much younger.

A Beautiful Day

The stage is set for Joe to enact bloody vengeance. He stalks through the Governor's mansion, laying waste to the armed guards. Again, Ramsay keeps this off screen – we only see the feet of dead men sticking out from doorways, their bodies blocked by whatever object they happened to fall behind after Joe smashed their heads in. Joe finally reaches the Governor.And the Governor is already dead.His throat is ripped open, and he lays, eyes gazing blankly up at Joe – and at nothing. Again, Ramsay has denied us the violent catharsis. "The scene towards the end of the film, where he goes to the governor's mansion expecting answers, and he finds the guy dead, so he can't satisfy his desires... that scene is a mirror scene for both him and the audience," said Bini. "You're not satisfied. You never get the satisfaction of seeing the violence you think you're going to see or getting the answers you think you're going to get. That whole feeling is what keeps you watching the film...you keep watching because you're expecting some kind of satisfaction that never happens."By the time You Were Never Really Here ends, Joe is still a broken man. He's rescued Nina, and she offers up a smattering of hope. "It's a beautiful day," she says, looking out at the sunshine. Joe agrees that it is, indeed, a beautiful day. But there's the lingering sense that while the body count has climbed, and while Nina is safe, for now, there's still unfinished business lurking. Lingering. Waiting for a moment that will never come.You might think this is all the result of constant chopping. That somewhere, there's a three hour cut of You Were Never Really Here that adds all the missing pieces back in. But that's not the case. "There was never a long cut of the film," said Bini. "It just didn't support that — didn't need to support it. But what's marvelous about Lynne's films is, unlike some filmmakers, the order of the imagery actually matters. The difference between "he puts the milk glass down now" as opposed to "he puts the milk glass down later" is huge. We never felt we had to make it shorter. We just had to get it right, and so that's what we did in the last leg of it."What makes You Were Never Really Here one of the best movies of the year is not what it shows us, but what it doesn't show us. Here is a film that has the nerve to trust us to fill in the blanks; to mold the story into shape on our own. It's rare to see a film have such faith in its audience. And it's worth celebrating. This approach is also an ingenious way to put us within the fractured headspace of Joe. Joe's mind is frequently swimming with toxicity; his thoughts are shattered, and the story unfolding is shattered as a result. In less skilled hands, You Were Never Really Here's deliberately vague storytelling might be a weakness. It might even come across as maddening. Yet it never does here. We are given all the pieces we need to put a puzzle together ourselves. We may not like what we see when that puzzle is finally assembled, but it is assembled none the less. In this sense, You Were Never Really Here is visual storytelling at its finest. No long speeches, no lengthy exposition, no on-the-nose dialogue is needed to move us from point A to point B. Instead, Ramsay relies on the viewer to make the journey themselves. To follow Joe down dark, dangerous alleyways and see where it all leads.