'Westworld' Spoiler Review: 10 Questions From 'Trompe L'Oeil'

And with a huge plot twist and the first death that cannot be quickly fixed in a lab, Westworld has taken things to the next level. As usual, I have ten questions, some literal and some just acting as an excuse to talk about certain aspects of the series. Let's begin.

What Does "Trompe L'Oeil" Mean?

As with the titles of past episodes, calling the seventh episode of Westworld's first season "Trompe L'Oeil" speaks volumes about every plot thread, every character motivation, and every twist, both major and minor.

French for "deceive the eye," trompe l'oeil is an artistic technique that was given its name during the Baroque period but has existed for thousands of years, appearing in ancient Greek works before being utilized in the Renaissance and beyond. Everyone knows what the term is referring to even if they don't know the term itself: the use of perspective to create the illusion of depth in a two-dimensional work of art. By utilizing depth and suggesting that some objects in a work are closer and further away than others, artists are able to create a more realistic image, tricking the viewer into finding reality where none actually exists. It's cornerstone of art and a key divider between realistic and abstract forms of art.

The term does a fine job of summing up Westworld the theme park: a land where nothing really matters, where all interactions are scripted, where tragedy and pain and pleasure are carefully constructed, but done so with such care and detail that it takes on the illusion of reality. It's surely no accident that trompe l'oeil is a Baroque term. Like the paintings and sculpture of that time period, Westworld is intended to be unambiguous, dramatic, and instantly pleasing, a canvas where thousands of tiny details serve an instantly gratifying "big picture" that is difficult to misinterpret.

But like any artist, Westworld founder Dr. Robert Ford knows more about his painting than those who paid for it and those who pay to see it. He may smile and nod while you give him your interpretation of his work, but only he knows his true intentions and what it all actually means and how it all hangs together. It's his painting, his world. Everyone else is just unfortunate enough to have walked into it.

What Is Delos' Actual Plan For Westworld's Technology?

One of Westworld's quieter threads has begun to heat up over the past two episodes with the arrival of Tessa Thompson's Charlotte Hale, a member of the Delos board who has come to oversee a "transition" at Westworld and oust Dr. Robert Ford from his position of power. In "Trompe L'Oeil," we were able to hear more about the company's intentions straight from Ms. Hale herself: Dr. Ford cannot be fired, so he will be persuaded to retire; the company doesn't have much interest in running a cowboy theme park, but it does have uses for the technology being used to operate that cowboy theme park; they do not know how a significant portion of the park actually operates because Dr. Ford has refused to back up his data off-site and remains the only living person to know what makes Westworld really tick.

And that solves last week's big mystery. Head of quality assurance Theresa Cullen (Sidse Babett Knudsen) may have been using a stray Host to steal park secrets, but she wasn't assisting a rival company. She was tasked with internal espionage by her superiors at Delos and Knudsen's performance tells us everything we need to know – she really, really didn't want to be a part of this. Perhaps more than anyone else working at Westworld, she was aware of what Dr. Ford is capable of doing and how far he will go to protect his dominion. Recall their conversation in that park restaurant a few episodes back, where he literally put on a display of God-like power within the park to prove a point. She, like the other Delos representatives, are but mere mortals, guests in God's domain.

The lingering question now is what Delos actually wants to use Westworld's code to accomplish and how they intend to apply robot cowboy technology to the outside world. Considering the events that end this episode, we will probably know soon enough.

Where Do We Draw the Line on Robot Sex?

There are several ways you can have a relationship with a Host in Westworld.

You can be like Charlotte Hale. You can be wealthy enough to actually indulge in what Westworld has to offer and take full advantage of the fully functional recreations of human beings available to you. While the Delos board member seems to have no interest in actually going down to the park and playing cowboy, she's perfectly happy to borrow outlaw Hector Escaton (Rodrigo Santoro) for a few hours, utilizing him as the world's most advanced sex toy. For Charlotte (and park guests like Ben Barnes' Logan), they approach the illusion of Westworld with constant self-awareness – none of this is real, so why should you not have a good time? Break it, abuse it, use it. Who cares? It's all going to get reset in the end.

You can be like William (Jimmi Simpson). You can be wealthy enough to actually indulge in what Westworld has to offer, but have no interest in treating the faux world around you as a sandbox for whatever game you want to play. You can meet the illusion halfway and let the roleplay go beyond cowboy cosplay. For William, Dolores isn't just the Non-Playable Character accompanying him on a violent quest. She isn't just an RPG ally whose only use is to carry all of the stuff that won't fit in your inventory. He's embraced Westworld in the ways that Dr. Ford has always wanted guests to embrace it. He's fallen in love (or at least in something) with a woman who was built and programmed in a lab. But here's the concern: if Dolores is an artificial creation meant to simulate humanity who has broken free of her programming and is capable of making her own decisions, when does she deserve to be treated as something more than a cog in a machine? At what point does an exactingly recreated human become human?

Or you could be like Theresa Cullen and learn that your longtime colleague and lover has actually been a Host all along and he didn't even realize it. The Hosts are tools, but up to this point, we've only been granted a glimpse at one of their uses. Now, we have seen what they can accomplish if wielded like a weapon by someone unafraid to destroy lives to protect his life and work. But we'll get there shortly.

Was Clementine's Beating the Most Disturbing Scene Yet?

Westworld has been a violent show since its first episode, using cruelty to surgically examine the limits of what we find acceptable in our entertainment. While there are undeniably some viewers who enjoy Westworld as a bloody action show with wacky twists (and that is their prerogative), the series has always been critical of itself. Self-awareness is its secret weapon – it knows we enjoy fake violence in our movies and shows and video games, so it tests our limits. Are you not entertained?

Take the scene where Clementine (Angela Sarafyan) is "tested" by Charlotte Hale before a small audience of park heads. When viewed as an abstract, we're watching two programs run through their operations. Take one step back, and you're watching one robot attack another robot, both of whom will forget about this event in a matter of seconds. But take another step back and you're looking at a man viciously assault a defenseless woman in a scene of violence that is extreme even for an HBO series. Look upon the passive faces of Dr. Ford, Theresa Cullen, and Bernard Lowe and despair – there is no sympathy for the illusion of abuse and violence. All they are the ones and zeroes.

Think about Clementine, who spends her days stuck as a prostitute because she needs to support her family's failing farm. But only for a few years. She'll be back eventually. This job is only temporary. Her humanity, while carefully constructed, informs her every moment. When she is beaten to the ground to prove a point to the men and women who built her, it's hard to forget her backstory. It's easy to wonder if she's thinking about her family as she fears for her life.

Of course, Clementine does fight back and take down the Host who assaulted her, but even this sense of agency is a bug planted by Theresa and Charlotte to lay the groundwork for Ford's dismissal. She may look human, but she's not human enough to be anything but a pawn. And when Bernard takes the bullet for his boss and accepts responsibility for (the clearly staged) act of Host sabotage, it's just a repeat of what we just saw: a pawn programmed to do what he must do to serve the whims of his master. But we'll get there.

How Does Maeve Plan to Escape?

After taking the spotlight last week and receiving an intelligence boost that makes her the most dangerous being in Westworld, Maeve (Thandie Newton) retreated to the background in "Trompe L'Oeil." And for good reason: she's now smart enough, aware enough, to think about her actual future and not the scripted hopes and dreams she will never be able to obtain. That's the tragedy of her learning Clementine's backstory in this episode – Maeve now knows that her colleague will never make it back to the family farm. She'll probably die today and wake up in the same place over and over again.

So we watch Maeve live within her usual loop, but with full awareness of her surroundings. She goes through the similar motions, repeats the same lines of dialogue she always has, but with a tinge of melancholy and rage that were absent before. It's quietly spectacular work by Newton, who has to play new emotions on top of material we've already seen several times before.

In terms of plot, the most important revelation is that Maeve is no longer under control of the park technicians. When they freeze the occupants of the Mariposa so they can enter the scene in their protective white suits to retrieve a Host, Maeve does not halt along them. She has total control of her body. She is her own person. And so she plants the seeds of what to do next in a conversation with Felix and Sylvester, who are in such deep shit at this point that they essentially have to go along with whatever Maeve says. It's time to escape.

But how? And what is waiting for Maeve beyond the park limits? We've been wondering since episode one what the world outside of the park looks like and it's starting to look like Maeve is the character who will provide that answer.

Why Do Two Different Characters Reference a "Blood Sacrifice"?

Consider this our weekly "I have no idea what this means, so let's throw some stuff at the wall until we know more" section.

Early in "Trompe L'Oeil," Charlotte Hale explains her plan to remove Dr. Ford from his position in Westworld, slyly noting that they are going to require a "blood sacrifice" to get the job done. It's a dark and theatrical phrase from a woman who has quickly revealed herself to be a dark and theatrical person. Of course the woman who has the robot outlaw tied up in her bed would view the world as a giant game.

But then the same phrase rears its head much later in the episode, when the truth about Ford and Bernard (more on that in a moment) is revealed and Theresa Cullen meets her untimely end. Before she exists stage right, Dr. Ford uses the same words – he too requires a blood sacrifice. Theresa doesn't have enough time to react or to question why he says the same phrase that Charlotte did in a private conversation a day earlier. She's out of time and Dr. Ford isn't one to give away his secrets, even to a doomed colleague.

So let's talk about this. As far as I can tell, there are two obvious paths for this take. It could be as simple as Ford knowing that specific phrase because his power over the Host extends outside of the park. Hector Escaton, naked and tied up in bed, was present for Theresa and Charlotte's meeting. If Ford can control armies of hosts with a specific word or hand gesture, what's to stop him from using them as spies, to listen in on conversations and report back to him? In that case, the use of "blood sacrifice" would be simple cruelty – he heard their entire conversation and is throwing the phrase back at her in her final moments.

The wackier angle, the one that I don't really believe but I'm going mention anyway, is that there are other unaware Hosts lurking around the real world besides Bernard. And maybe (maybe!), Charlotte is one of them.

Nah. That has to be nah. Right? Right?

How About That Final Scene?

We've been edging around it for a few thousand words now, so let's just get to it.

In the final scenes of "Trompe L'Oeil," we learn a series of increasingly horrifying truths. Ford is maintaining a secret workshop underneath the secret house where he stores his secret robot family. That secret workshop contains technology that can build a new Host in a matter of days, far from the prying eyes of Delos. And then, we learn that Bernard didn't bring Theresa here to expose this, but because he was under orders from Dr. Robert Ford. His creator. Because Bernard Lowe is a host and like the other hosts, he didn't even know it. He never questioned his existence. Because why should he?

Even as he smashes Theresa Cullen's head into a wall and ends the life of his friend and lover, he remains blissfully unaware of the things he's programmed to ignore. He can't see the door to the lab. The plans describing how to build a Bernard robot look like nothing to him. God wants him to take care of that woman? Sure thing. Thou shalt not kill, but thou shalt have no other gods. When God says jump, Bernard can only ask how high.

It's as unsettling as anything we've seen on Westworld so far, our first "real" death in a show where characters have died thousands of times but always come back, good as new. The scene is even shot in such a way to rub salt in the wound. Theresa is bludgeoned in the background, out of focus, while a brand new host is slowly printed in the foreground. Human life is secondary to Dr. Robert Ford, a distraction from his Creation.

It's an intensely disturbing scene packed with revelations, but in true Westworld fashion, it also finds time to ask more questions. If Dr. Ford can build Hosts in secret, how many other unregistered hosts are floating around? How many are working at the park? How many are doing his bidding out in the real world? And unless my eyes deceive me, this secret lab is where Bernard has been conducting his off-the-record, Alice in Wonderland-recommending conversations with Dolores. When have those conversations been taking place? What did Bernard think he was doing when he was interrogating her? Westworld, like Lost before it, is a show built on sharing half-truths and offering morsels instead of full servings. Each puzzle piece you are given reveals that the picture on the box is completely different than the one represented by the pieces on the table.

What Happens When Anthony Hopkins Actually Gives a Damn?

You're not going to find many people who think Anthony Hopkins is a bad actor. That's categorically untrue. He's a phenomenal performer. An all-time great. But let's face facts: a look at his IMDb page (and his recent appearances in television commercials) reveal an actor who likes to work and stars in a lot of crap and sometimes sleepwalks through major roles. Granted, Hopkins sleepwalking is usually more impressive than other actors giving it their all, but you can tell.

One of keys to Westworld is that it seems to have Anthony Hopkins' full attention and "Trompe L'Oeil" let him really dig his heels into some great material. Hopkins radiates intelligence by default, but his greatest talent has always involved nudging that intelligence toward whatever emotions color a particular character. For Dr. Robert Ford, that intelligence has been something of a blank poker face for six episodes – you never know what he's thinking while knowing, at all times, that he never stops thinking. His motivations exist just under the surface and he only offers a glimpse here and there, a quick sample to suggest that you really don't want to see any more beyond that.

The mask has come off and Hopkins has stepped up to the plate. It's now very clear why Bernard Lowe is the only other character on the show that Ford has treated with anything resembling respect. It's because he created him. He built him in a lab. All other humans are suspect. They don't understand him. They don't understand Westworld. They certainly wouldn't understand his need to maintain robot recreations of his own family on a house hidden in the park. That God complex isn't just for show.

And Hopkins, sinister, terrifying, and enjoying his final conversation with Theresa Cullen just a little too much, has given us a new kind of villain. Last week, I wrote about him as a nostalgic dork, the kind of person who lets their childhood obsessions dominate their adult life. This week, that portrait of arrested development came into further focus. If Ford was a young man in 2016, he'd revel in the anonymity of internet message boards, where you can hurt people without seeing their faces. Human life is worthless when you have your head stuck in the cloud.

How Does Arnold Fit Into All of This?

Let's tie the new revelations into some pre-existing conversations. Ahem.

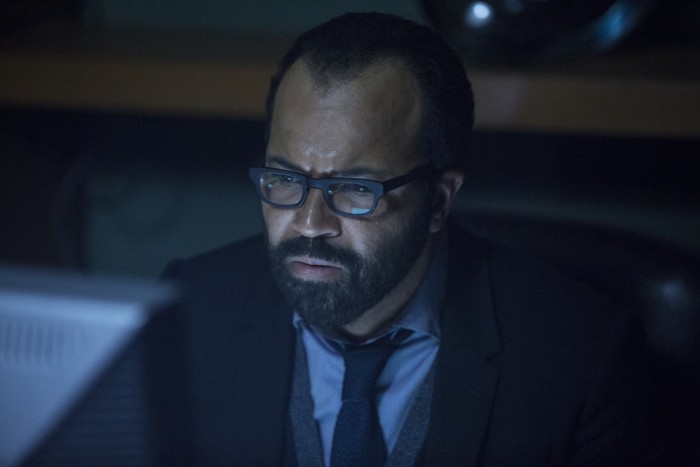

What if Bernard is a robotic recreation of Arnold, which would explain why the nostalgic Ford likes having him around so much and explain why the voice Dolores hears in her head sounds so much like Jeffrey Wright while also suggesting that those scenes of Bernard talking to Dolores are actually flashbacks to Arnold talking to Dolores?

Maybe?

Is Westworld Worth More Than the Sum of Its Twists?

Every week, I'm excited to watch Westworld and every week, I'm excited to write about it. But "Trompe L'Oeil" exposes the show at its worst and at its best and we need to talk about this.

At its best, Westworld is an engine for unsettling ideas and satire and propulsive science fiction storytelling. I love that this show has made me think about Baroque art and computer programming and theme park design and video games. As an experience, I often find it overwhelming, a series of such intelligence and assembled with such care.

At its worst, Westworld offers all of that thematic richness while failing to find a human center. While Dolores has emerged as a hero to root for, everyone else continues to exist as a brilliantly acted delivery mechanisms for the plot. Jeffrey Wright and Thandie Newton and Ed Harris are doing fine work, but affection for their performances doesn't always translate to affection for their characters. For example, the murder of Theresa Cullen was a shocking moment, but it wasn't a heartfelt moment. I had no genuine love for the character and I care more about how her demise will rattle the story than I do about her actually, you know, dying.

Westworld continues to feel an awful lot like Lost, a comparison I approve because that show that was nothing short of wonderful until its botched final season. But Lost has something Westworld does not: a cast of characters whose personal lives feel like they matter beyond the mysteries they're embroiled in. I remember shedding tears when Boone died in the first season of Lost. I remember how the light in the hatch represented a continuing mystery and emotional catharsis for Locke, who took that death as hard as anyone.

Right now...the missing-in-action Elsie is fun and William is a sweet guy? Outside of Dolores, whose personal journey is deeply intertwined into mystery and ploy that I cannot tell if I love her or love the idea of her, there are no characters I'm actively excited to see when they arrive on screen.

I'm on board with Westworld for the long haul. The show is too smart, too literate, and too daring to ignore. But if it's going to be a great show and not just a very, very, very good show, it's going to have to let us care about the people trying to break into that puzzle box of a plot.