The 11 Weirdest Films From David Cronenberg: From 'Shivers' To 'Maps To The Stars'

David Cronenberg's new film Maps to the Stars is in theaters and on VOD, and every time a new film arrives from the director I end up going back through his years of prior work to find new connections and ideas. It takes a while, sometimes, to really find where one of his films sits in the grand scheme of things. (I'm still trying to sort out Cosmopolis, frankly.) This time, I kept focusing on the weirdness of Cronenberg, which is what everyone focuses on in his films at some point. But this was more about the unusual connection between his subjective visions of reality and our own experience rather than eye-popping visuals. This isn't an overview of David Cronenberg's full career, but just to set out an organizing principle, what follows are 11 of the Weirdest David Cronenberg films, as they relate to our own lives.

Note, there aren't big glaring spoilers for any of the films here, but I'm assuming you've seen The Fly, and there are definitely some hints about the endings of a few other films on this list.

***

11. Maps to the Stars (2014)

11. Maps to the Stars (2014)

The Los Angeles residents we meet in Maps to the Stars, a film which is mordantly satirical and far less tied to reality than it first appears, are entirely broken. The "best" people in the film are tainted by a tacit acceptance of horrible behavior from the film's worst examples of humanity. And those worst examples perform a whole range of unsavory actions, many of them in the service of personal ambition. And while there are some more extreme examples, nothing is quite as bizarrely disgusting as the singing and dancing response one character has to the death of a young boy. It's the most extreme and specific vision of schadenfreude I've seen in a while, and an overtly garish way to show how dramatically opposing impulses can collide.

We'll come back around to the idea of the effectiveness of Cronenberg's outre concepts being directly linked to their place in reality, but his most recent film, which also happens to be one in which a disconnect from reality is only gradually revealed, is a great place to start.

***

10. Rabid (1977)

10. Rabid (1977)

A motorcycle accident leads to experimental skin graft surgery, which leads to an unusual growth in a young woman's armpit that feeds on human blood, with the victims of her embrace turning into rabid flesh-hungry monsters of their own. The events of Rabid are definitely bizarre, but the film is so early in the development of Cronenberg's ability to build whole societies that it rarely transcends odd to become powerful, and the limitations of lead Marilyn Chambers keep it campy and occasionally forced. In the realms of the weird, however, there's nothing quite like an anus-like opening in a woman's armpit that conceals a barbed and bloodthirsty tentacle. What really sticks with me at this moment, however, is that reflections of the film, from Marilyn Chambers' style to the overall structure, are impossible to miss in Under the Skin. (Whether intentional or not on the part of Under the Skin's creator Jonathan Glazer.)

***

9. Shivers (1975, aka They Came From Within)

9. Shivers (1975, aka They Came From Within)

Cronenberg's first commercial feature is in some ways a simple monster movie — parasites infect a host, then create uncontrollable sexual urges in that host, which facilitate further transmission — but it is a monster movie that flips any morality or conceptual "return to normality" right on its head. Embracing the sexually ambiguous '70s, the most vivid weirdness of Shivers is an "all-in" pool party in which people roil and couple in the water like frenzied fish. But the deepest weirdness is the calm acceptance with which the film views its final outcome. Right from the beginning there's something we'll come back to often: the ability to stay calm while depicting a "normal" human order being destroyed.

(Shivers was released in the summer of 1975, right around the same time J.G. Ballard's novel High-Rise arrived. Oddly, High-Rise features some conspicuously similar features, such as an apartment block setting inhabited by citizens who are ultimately divided into two groups. We'll see Ben Wheatley's adaptation of High-Rise later this year.)

***

8. Scanners (1981)

8. Scanners (1981)

At the height of the Canadian tax-shelter financing days, Scanners funneled funds into a pulpy sci-fi tinged nightmare of evolution. This story of a clash between violently alienated telekinetics, the scientists who create them and the businessmen who would control them is a ruthlessly condensed take on Brian De Palma's Fury; or you could call it almost an alternate take on the X-Men. The weirdest part of the whole thing isn't the exploding head seen early in the film, nor even the outsized and biological sculptures such as the one that allows an artist to literally retreat into his own head. No, it's the non-performance from Stephen Lack, whose total lack of presence turns out to be just right, thematically at least, for the role of a man whose head is so full of voices that he is shut off from any semblance of humanity.

I've rationalized Lack's performance in that way for years, and after the recent Criterion Blu-ray release of the film, Lack said the performance was a conscious choice that was in part rooted in the fact that Cronenberg was basically writing the movie on the fly. Lack often didn't know precisely how his character had ended up in the current scene, because previous scenes hadn't been written yet. So he neutralized the whole performance. (So he says.) One way or the other, it's a chilling and off-putting establishment of a conscious distance from any emotional response to life.

***

7. The Brood (1979)

7. The Brood (1979)

"Reprehensible trash," sneered Roger Ebert in his review. Rage, cycles of abuse, and parenthood are intertwined in what is widely known as the director's most personal film, rooted as it is in the end of his first marriage and a custody battle for his daughter. The Brood lacks the composed distance of some of the other films under consideration here, as it trades cool for viscera. Messily stirring up images of a broken mother (echoed in Maps to the Stars) and the monstrous "children" that trauma can bear, The Brood is an emotional horror film with blood and guts spawned of deep fears we all share. If we accept the personal relation to his own life as the guiding principle, however, Cronenberg does finally turn his observational eye back on himself, as the film's conclusion ultimately calls the outcome of his own actions into question.

***

6. The Fly (1986)

6. The Fly (1986)

David Cronenberg's most consistently unnerving tendency is not related to gore or body horror. It's not the collision between old and new forms of humanity. It's that ability to look at the most disturbing shifts in condition with an eye that is dispassionate — or, worse, curious and accepting. We see it at the end of Shivers and Videodrome; the evolution in Rabid, and perhaps most specifically, the the progression from Seth Brundle to Brundlefly in The Fly. Brundlefly is not a creature of malice, but a thing of instinct, even purity. Seth Brundle looks at his transformation as a scientist would appraise a subject; that subject just happens to be himself. Cronenberg watches it all go down with only the occasionally puffy score from Howard Shore to indicate that his pulse is rising above normal.

***

5. Dead Ringers (1988)

5. Dead Ringers (1988)

From here on out we're deep in the weeds. While not as overtly wild as some of Cronenberg's other films, Dead Ringers is plenty lurid, with its image of deranged gynecologists who perform operations clad in red surgical robes. (And it has the benefit of being heavily inspired by real events.) Once again, the closer he gets to "reality," the weirder some of Cronenberg's films seem. Dead Ringers is a rorschach blot of a split brain, with the twin characters played by Irons working out their struggle for dominance and independence. Additionally, it offers an unflinching consideration of just how far we'll go to maintain a connection with someone, and is also a horrifying image of the way in which some men relate to women.

***

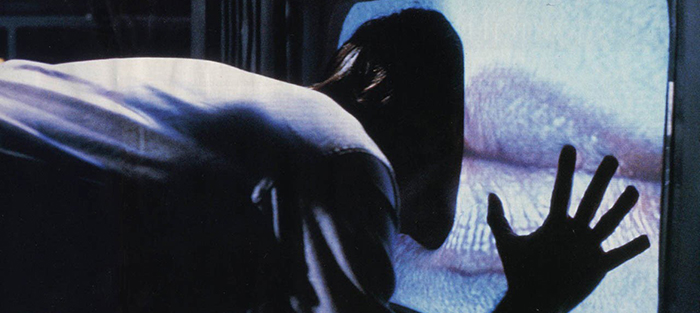

4. Videodrome (1983)

4. Videodrome (1983)

We don't want to think about media changing us, but Videodrome suggests that the effects of media consumption are incredibly powerful and wildly unpredictable as cable TV operator Max Renn discovers that a violently alluring pirate video broadcast is actually a control signal with the power to kill. There's a media prescience here, as Videodrome saw the all-encompassing future of the moving image, but there's also something deeply reactionary in Cronenberg's story — the videodrome signal is, after all, designed to affect those attracted to deviant images of sex and violence. Exactly the stuff, in other words, of Cronenberg's own films, for which he was targeted in the press. If only other responses to one's own critics were as imaginative as this.

***

3. Naked Lunch (1991)

3. Naked Lunch (1991)

The discomfort, paranoia and spiritual violence of a life spent opening up the deepest recesses of your consciousness to strangers is deeply embedded in Cronenberg's adaptation of several works by William S. Burroughs. Naked Lunch finds some middle ground between visualizing the hard work of being alone in a room with a writing device and a blank page, and the unbounded leaps of conceptualization that produce creative works. If those leaps are into places that are as disturbing as those in Naked Lunch, so much the better. Here, Cronenberg performs his own creative alchemy and upends the very form of the biopic by merging concepts from Burroughs' work with moments from his own life. In doing so, he captures the process of writing and mythologizing our own lives, as horrifying a process as it may be.

***

2. eXistenZ (1999)

2. eXistenZ (1999)

Released not even a month after The Matrix hit the US, this heavily meta-textual and multi-layered video game narrative had no chance to make an impression. As it has aged, however, something unexpected has happened: many of its criticisms — of video game writing, reliance upon cliche, sexualization of female characters, and navel-gazing self-obsession — have become more appropriate than they were sixteen years ago. In a way that has always felt like a direct tie to Videodrome, eXistenZ is a nested set of realities; the one that occupies most of the film is like a cartoonish rendition of GamerGate. And while it lacks a conclusive ending, hanging on a question mark rather than a full stop or even an exclamation point, even the broader reality seen in eXistenZ asks that uncomfortable question about a correlation between behavior inside games and in the "real world." Videodrome has always seemed like Cronenberg's most technologically prescient film, but eXistenZ turns out to be eerily visionary as well; we just needed some distance to see it.

***

1. Crash (1996)

1. Crash (1996)

If this was a "best of" list Crash would only be near the top, but for this reckoning there should never have been any doubt. Going back to the idea that the closer Cronenberg pushes towards an intersection of his imagination and our reality, the weirder things get, this is a deeply and wonderfully uncomfortable movie. An imagined reality of sexual desires fulfilled, man-made extensions to build and preserve bodies, and a conduit of sexual energy passing between them, Crash posits a connection between "natural" and "unnatural" that calls those very concepts into question. The link between technology and sex has always existed, especially in film, but as with so many of his other films Cronenberg makes it weird merely by showing the images that have long danced on the edge of our peripheral vision. We can't come to terms with ideas unless we can talk about them, and Crash says that it's weirder not to talk about this stuff than to confront it head-on.