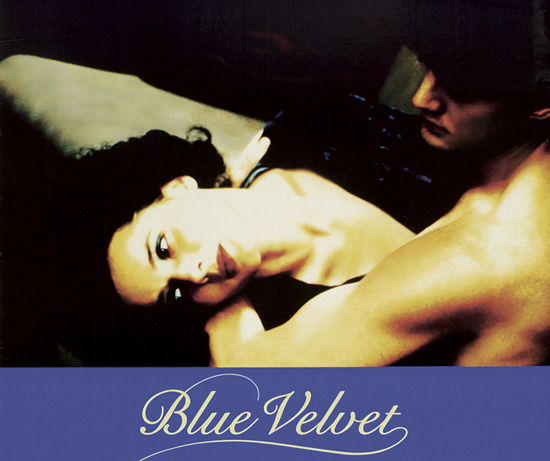

Twenty-Five Years Later, Celebrate The Potent And Troubling Dream Of David Lynch's 'Blue Velvet'

Twenty-five years ago, David Lynch held a crystal clear mirror up to the face of America. Blue Velvet, which had played festivals in Montreal and Toronto, opened in the US on September 19, 1986. It was mainstream America's real introduction to the private world of David Lynch. Eraserhead was still a cult film. While many people had seen The Elephant Man and some (not many) had seen Dune, few were prepared for the deeply idiosyncratic dreamscape Americana seen in Blue Velvet. Attacked for depicting a savage sexuality rarely seen on screen, the movie attracted no shortage of negative attention, but it quickly became regarded as a classic.

After twenty-five years Blue Velvet's mysterious and musical vision of middle-American life remains seductive and powerful. Its gallows humor still earns laughs, and a peculiar clash of of classical Hollywood and noirish styles draws viewers in to Lynch's unique world. The classic and noir impulses came out of Lynch's own fondness for movies, but combined with his depiction of raw, violent sexuality they suggested something specific. That is, the deranged sexual power games in Blue Velvet aren't anomalies; they're what was always going on when the camera panned away in movies of the past.

The film established the career of Laura Dern and prevented Kyle MacLachlan's image from being lost in the sandstorm of Dune. (MacLachlan's look as the young Jeffrey Beaumont was actually based on Lynch's own sartorial manner.) More than anything else it gave Dennis Hopper a framework in which to create one of the strongest, ugliest and most frightening characters ever seen on the silver screen: the raging gangster and sexual manchild Frank Booth.

The film's twenty-fifth birthday is something to celebrate. As Jeffrey says when making a toast in the film, "here's to an interesting experience."

As I said when I looked back at Aliens, I don't really go for nostalgia. I made an exception there, and I'll make another here, because with respect to my own personal history with and interest in film, Blue Velvet may be the most important movie I've ever seen.

Before I saw Blue Velvet I was a Star Wars kid. I saw the Lucas blockbuster in '77, when I was five, and it immediately defined what I wanted out of movies: spectacle, effects, and the whiz-bang rocketship elements that kids love. For the next decade I was primarily drawn to movies in that vein. When I saw Robocop or Aliens I might recognize concepts that went deeper than the film's basic action, but I was really there for the effects, the big stuff.

I didn't see Blue Velvet in 1986. I knew what it was; I was aware of the reputation it quickly acquired. I have distinct memories of the poster, and the incongruity of seeing it displayed in a Midland, TX. mall cineplex ticket lobby. The Siskel and Ebert review of the film provides a tidy summary of what I knew about the movie. Ebert praised Lynch's direction, but sharply criticized his treatment of actors. "Sure, the movie's well-made, but the more I thought about it, the less I liked it." Here's the review, which also provides a convenient plot synopsis:

I saw the movie in '88 or '89 after a friend accosted me at school. "I watched this movie last night. Blue Velvet. It was the most insane thing I've ever seen. It's on again tonight. Come over." The crisp opening imagery, droll comedy and narrative non-sequiturs, such as the ear in the field, hooked me. By the end, I got it; which is to say, I got movies. That cliche unveiling took place: I knew what movies could do as a storytelling medium that went way beyond the big effects-based stuff I'd loved until that point.

Blue Velvet is a movie with everything on the surface — from the weird courtship between Jeffrey Beaumont and Sandy Williams (Dern) to Frank Booth's insistence that Dorothy Vallens (Isabella Rossellini) not look at him during his sexual dominance, to the simple voyeurism practiced by Jeffrey, and therefore by us. I was sixteen or seventeen when I saw the film, and the movie's use of imagery and cinematic syntax, presented almost as a fairy tale, was my perfect entry point into 'real' movies. Watching it now I still get a thrill, a little zing of an unusual delight.

I wouldn't necessarily argue that Blue Velvet has any special power to change perceptions of cinema, but many years ago it had that power for me. Because Lynch's tale is a particularly exaggerated, concentrated piece of cinema, its power was potent. If I hadn't seen Blue Velvet when I did I probably would still have become enamored with film to such a degree that I oriented much of my life around it. I do know that what I saw on the screen that night was the catalyst for a great many things that are still a big part of my life.

(The movie also taught me something about dealing with psychopaths: be calm. And suave. "So fuckin' suave!" Being a bit of a psychopath yourself doesn't hurt, either, I suppose.)

As a creative act, the film actually began with the image of a man finding an ear in a field. After finishing The Elephant Man, Lynch met with producer Richard Roth, who had read another Lynch script, the still-unproduced Ronnie Rocket. Roth asked if Lynch had anything else and the young director said he only had ideas.

I told him I had always wanted to sneak into a girl's room to watch her at night and that, maybe, at one point or another, I would see something that would be a clue to a murder mystery. He loved the idea and asked me to write a treatment. I went home and somehow I pictured someone finding an ear in a field.

The project was pitched to Warner Bros., and Lynch wrote two drafts, which he says were horrible. (This has always heartened me; to think that something like Blue Velvet began as a couple of disowned script drafts should give any young writer a lot of hope.) Eventually, after Dune, Lynch got Dune producer Dino DeLaurentiis to buy the script from Warners. More drafts followed, and with a real script in hand Lynch got Dino to grant him final cut on the eventual project by cutting his fee and the film's budget in half.

Dune had been a massively traumatic experience for Lynch, but it provided him with the relationship with DeLaurentiis that led to Blue Velvet, and gave him a leading man in Kyle MacLachlan. Many other supporting actors from Dune turned up as well. Jack Harvey, playing the father of Jeffrey Beaumont, wasn't in Dune, but he still looks like a Harkonnen in his hospital bed, encumbered as he is with a frightfully exaggerated set of medical dressings.Blue Velvet continued Lynch's working relationship with many actors, but it was his first collaboration with composer Angelo Badalamenti. Their meeting was almost accidental — it came about when the musicians Isabella Rossellini rehearsed with for her nightclub scenes just didn't work out. Lynch was skeptical of Badalamenti at first, but the composer quickly got exactly the results Lynch wanted, and partnership was born that would span years.

As is always the case in filmmaking, there were other accidents and near-misses: Helen Mirren was a possible Dorothy Vallens for some time, and Lynch credits her with helping him work out issues in the script. Hopper's Frank Booth character was originally written to mime Roy Orbison's song 'In Dreams,' but in rehearsals Dean Stockwell owned it, and the performance went to him. On set, he picked up a work light thinking it was the prop he was meant to use, and that classic image was born.

I get the impression that David Lynch employs happy accidents more than almost any other filmmaker, and his intuitive, painterly approach to film is likely the major reason that Blue Velvet remains so alluring. The film is almost elemental as it shows the deep recesses of desire. It feels right, even when the things on screen are terrible and frightening, even inhuman. That smile on Dorothy's face when Frank Booth slaps her is among the most disquieting things I've seen in a film. And Frank's statement to Jefferey, "you're like me" – is there anything that could change you so deeply as having a guy like Frank say such a thing?

Despite that bonus for intuitive approach the film's long gestation period also makes this one of Lynch's most long-considered films. He and cinematographer Frederick Elmes, who had shot Lynch's short film The Amputee and some of Eraserhead, had plenty of time to work out approaches to some of the film's most famous imagery as the film remained a possible project in the years after The Elephant Man. Without that long conceptual birthing process, the film might not have emerged as the concentrated nightmare worth celebrating today.

The intuitive nature of the film was an early lesson to me in how movies can access the intangible, and how this most collaborative medium can produce stories that are intensely personal. The same lessons can be taught by any number of other films and directors, but for me it was this one. Simple stuff, sure, but valuable, and they're lessons that I've never forgotten. At this point in my life, when I want to be provoked, challenged or inspired (all three often happen simultaneously) I'd take the output of Luis Buñuel over that of Lynch. I never would have got to Buñuel without films like this one, however.

As a sort of birthday present, a press release recently went out announcing the 25th Anniversary Edition Blue Velvet blu-ray, which will hit on November 8. When that disc arrives it will have 50 minutes of footage previously thought lost. I reported on that months ago, but 50 minutes is a bonanza — far more than I ever expected.