The Unpopular Opinion: 'Inherent Vice' Is Top Tier Paul Thomas Anderson

(Welcome to The Unpopular Opinion, a series where a writer goes to the defense of a much-maligned film or sets their sights on a movie seemingly beloved by all. In this edition: Paul Thomas Anderson's Inherent Vice is one of the writer/director's very best.)

"I never remember plots in movies," writer/director Paul Thomas Anderson said in 2014. "I remember how they make me feel, and I remember emotions and I remember visual things that I've seen, but my brain can never connect the dots of how things go together." He was referring to Alfred Hitchcock's North by Northwest, though that quote could easily describe Anderson's own Inherent Vice. Trying to explain the film in a Wikipedia-style recounting of events is futile. It does not even come close to doing justice to the experience of letting the film's inscrutable mysteries wash over you.

With the release of Phantom Thread, it's time for re-ignition of the hype machine surrounding six-time Oscar nominee and cinephile darling Anderson. Naturally, when any acclaimed director puts out a new work, this prompts obsessive ranking and list-making. Anderson acolytes do not face nearly as daunting a task since he's only directed eight films (nine if you count music documentary Junun), but a fissure usually emerges when reappraising PTA. You tend to either favor his bold, vibrant early work like Boogie Nights and Magnolia or his controlled, precise recent efforts like There Will Be Blood and The Master.

Then there are his outliers. For 15 years now, the short, sweet and unclassifiable Punch-Drunk Love has won a passionate base of devotees (including Guillermo del Toro) who argue for its high ranking in Anderson's filmography. We're only three years out from Inherent Vice's release, a film as equally unclassifiable and unique in his body of work. But devotees need to lead with more vocal advocacy before it gets relegated to permanent bottom-tier status in the Paul Thomas Anderson canon. The film is an unabashed delight merging the artist's freewheeling, fun-loving instincts with the formal rigor of his later work. Fawn all you'd like over the restrained elegance of Phantom Thread, but Inherent Vice is far more of an impressive achievement and an emblematic calling card for PTA.

Anderson Wrangles Pynchon's Prose Into Submission

Paul Thomas Anderson is no stranger to ambitious adaptations, turning Upton Sinclair's Oil! into a brooding epic on American capitalism with There Will Be Blood and incorporating subtle shadings of Scientology's founding into The Master. Yet the effortlessness with which Inherent Vice unspools obscures just how difficult it was to bring to the screen.

Writer Thomas Pynchon's novels are notoriously difficult. (Shameful admission: my first brush with him in a college seminar resulted in defeat.) The plots are labyrinthine. Characters pop in and out, never obviously blaring their significance. Narration references a litany of cultural products, not all of which are real.

Perhaps the greatest, and most unheralded, achievement of Anderson's Inherent Vice lies in his script. He bottles up the essence of Pynchon in all its postmodern glory and unleashes it on screen. There's enough material in the novel to spawn a mini-series, yet Anderson manages to capture the full experience in just under two and a half hours without sacrificing what makes the book such an indelible read. Anderson never shies away from the hazy, confusing nature of the story because that's not just a stylistic choice. It's a part of the story's nature as Doc Sportello (played by Joaquin Phoenix) slowly connects the interlinked circles of the criminal, corporate and legal enterprises in the cases he pursues.

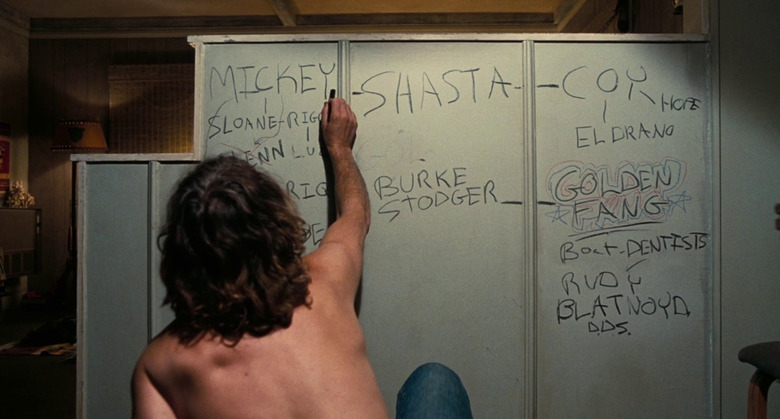

Rather than betraying Pynchon by making Inherent Vice a more user-friendly ride, Anderson manages to clarify and streamline the book. He cuts out a trip to Las Vegas from the novel which, entertaining as it might be, is rather tangential. He maintains the hyper-literate stylings of Pynchon by giving some of the novel's text to Sortilège, a small character in the novel who becomes a narrator in the film. And, better yet, Anderson even increases the mystery surrounding Sortilège and her trenchant insights by never clarifying her relationship to Doc. Could it be that she's a figment of his imagination or the product of a drug-induced hallucination? She becomes a mystery just like the true identity of the Golden Fang – is it a crime syndicate? A dental group? An old maritime schooner?

Ultimately, it doesn't matter. Pynchon does not rely on confusion because he wants to provide all the answers to the questions raised. He wants to provide an enveloping trip that subsumes us in the miasma of the world he creates, recreating the disorientation and disillusionment at the dawn of a new decade. With a well-calibrated mixture of translation and transcription, Anderson adapts a literary luminary into cinema with very little precedent in his own work or others. This is an accomplishment of deceptive difficulty, and not to mention, it would probably only merit significant attention had it gone terribly wrong.

It's one thing to craft the rules of your own universe where frogs can fall from the sky or a harmonium drops magically into someone's life. Reaching for the sky is a feature of Paul Thomas Anderson's work that has long endeared moviegoers. But there's something to be said for attaining a comparable level of virtuosity within a more tightly proscribed frame. Inherent Vice is a great Paul Thomas Anderson movie inside of a brilliant Thomas Pynchon adaptation, a duality only possible with a gifted filmmaker at the helm.

Anderson Conjures a Vivid Time and Place

Seriously, good luck to Quentin Tarantino's upcoming still-untitled project about the year 1969 and the effect of the Manson murders. Anderson already captured the ethos of the period in Inherent Vice, and in Los Angeles, no less!

The film unfurls in 1970, Anderson's birth year. Given the detail of the recreation and the way that zeitgeist infects every frame of the film, you'd think he was a fully conscious adult who had lived through it. Inherent Vice eschews obvious signifiers of time and place, trusting an audience to recognize a setting without a Creedence Clearwater Revival needle-drop. What makes this even more impressive than, say, Phantom Thread's vague backdrop of post-war 1950s Britain, is that Inherent Vice takes place in a transitional period between two decades with very distinct identities.

The hippie era of the '60s has clearly come to an end thanks to Manson, and the fallout from his murders and trial lingers like a cloud over the film. Paranoia and suspicion accompany all the things that once carried hope for liberation and equality. As a cop says when pulling over a rowdy car Doc is riding in, "Every gathering of three or more civilians is now defined as a potential cult." There's a sense of sadness accompanying the end of this era, playing out in both subtext and overtly through Doc's yearning for reunion with his ex-girlfriend, Katherine Waterston's Shasta Fay Hepworth.

It's clear to us that Inherent Vice presages the Nixonian and even Reaganite malaise of the coming decades, a conservative backlash in reaction to advances in many social movements. Characters like Doc, floating about freely in his dope-infused stupor, are becoming out of place in their own time. Yet none of them act as if their choices carry such monumental weight because people living through historical shifts are rarely aware of it. Thus, no one speaks as the mouthpiece of an era or makes statements that might seem predictive or ironic from a present-day standpoint.

Inherent Vice has none of the historicizing the contemporary like Anderson did in There Will Be Blood, nor is there the historical sprawl of Boogie Nights or The Master. Still, by focusing on such a particular point in time and drilling in to the specifics, Anderson taps into textured pleasures by luxuriating in the details of 1970.

Anderson Bares His Comedic Chops

Inherent Vice is probably Paul Thomas Anderson's Ted.

Before you laugh that off, hear me out. In an interview to promote The Master in 2012, Anderson spoke of his fondness for two – let's say, different – comedies:

I'd like to make a film like Airplane. That never gets old. Or Ted. It was a big hit. Why? Because it's great. Movies that are that big a hit are never fucking bad. I mean, there's no such... You know, people aren't that stupid, that movie's a hit because it's hilarious.

After making something as brooding and moody as The Master, it makes sense that Anderson would want a bit of a light palette cleanser. But rather than dropping his signature style to make a ribald comedy, he finds ways of incorporating this irreverent humor into Inherent Vice.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_7g0thJe_qY

Take, for instance, the banana scene. The obvious sight gag of Josh Brolin's Det. Christian "Bigfoot" Bjornsen fellating a chocolate-covered banana is just plain hilarious. It starts out seemingly innocent, but then the simmering sexual undertones boil over into all-out sexual innuendo. Our instincts tell us that Anderson, high-minded aesthete that he is, would never put in such a juvenile joke. And yet, there's Bigfoot ramming the phallic-shaped food into his mouth with accelerating velocity.

The Hollywood studio version of this joke would probably wallow in the luridness of Bigfoot's oral fixation. And yet, Anderson has him entirely out of focus, blurry in the foreground while Doc's increasingly revulsed reaction shows clearly in the background. What might be an immature gay panic gag instead serves as a demonstrative example of the bizarre power dynamic between two detectives operating outside traditional legal authority.

Anderson has spoken about watching Police Squad! clips on YouTube during smoke breaks and letting that influence trickle into Inherent Vice. There are no blatant homages or callbacks like there were to 2001: A Space Odyssey in There Will Be Blood or Let There Be Light in The Master. Instead, Anderson lets the spirit manifest itself in the film and animate certain sequences that might otherwise play more flatly. Phantom Thread makes use of humor, too, though in a far more conventional way with the kind of piquant British wit that spices up many a period piece.

The Abrahams/Zucker comedy style is silly but hardly sophomoric. The visual humor relies on active viewership, often working on multiple planes and underselling the comedic virtues of a given joke. There's no real reason, for instance, to have a pizza party at burn-out band The Boards harken back to Leonardo da Vinci's The Last Supper. But it rewards a viewer who's paying attention. By the time the shot's intention becomes clear, Anderson gives it about two seconds to register. (Contrast that with a similar setup from Robert Altman's M*A*S*H, which lingers on the tableau for nearly a minute.)

Among the most serious cinephiles, there can often be a hierarchy of taste that is based on objective taxonomy than we'd like to admit. Filmmakers deemed "serious" often tend to correspond with a certain level of erudition. They are serious because they require education to understand and appreciate, which makes their exaltation in turn tickle the ego of the person with the capability of exalting them.

Far too often, we equate the sophistication of a filmmaker's homages with the quality of their work. Boogie Nights recalls early Scorsese's vitality. Magnolia has ensemble work with a sweep that invokes Altman. Punch-Drunk Love toys with French New Wave techniques. There Will Be Blood boasts well-earned Kubrickian comparisons. Phantom Thread draws comparisons to Hitchcockian melodrama. Paul Thomas Anderson's antecedents are undeniably impressive. But declaring Inherent Vice a lesser film simply because it does not play into a familiar genre or riff on a director's filmography, whether consciously or not, establishes a subtle hierarchy of taste in his canon.

Inherent Vice is great because it's so distinctive, so purely PTA. The film combines both Anderson's verve and meticulousness while also miraculously fusing with the sensibilities of Thomas Pynchon. His ability to infuse what many consider lowbrow culture into a highbrow literary adaptation is a postmodern marvel. It might not be the film he had to make, but it certainly feels like only Paul Thomas Anderson could make Inherent Vice – a feat which alone should keep it from clustering with Hard Eight at the bottom of rankings. Don't try to overly intellectualize it, just let the feeling wash over you...