How Did This Get Made: Hackers (An Oral History)

Hackers + Revolution + Rollerblades = How Did This Get Made?

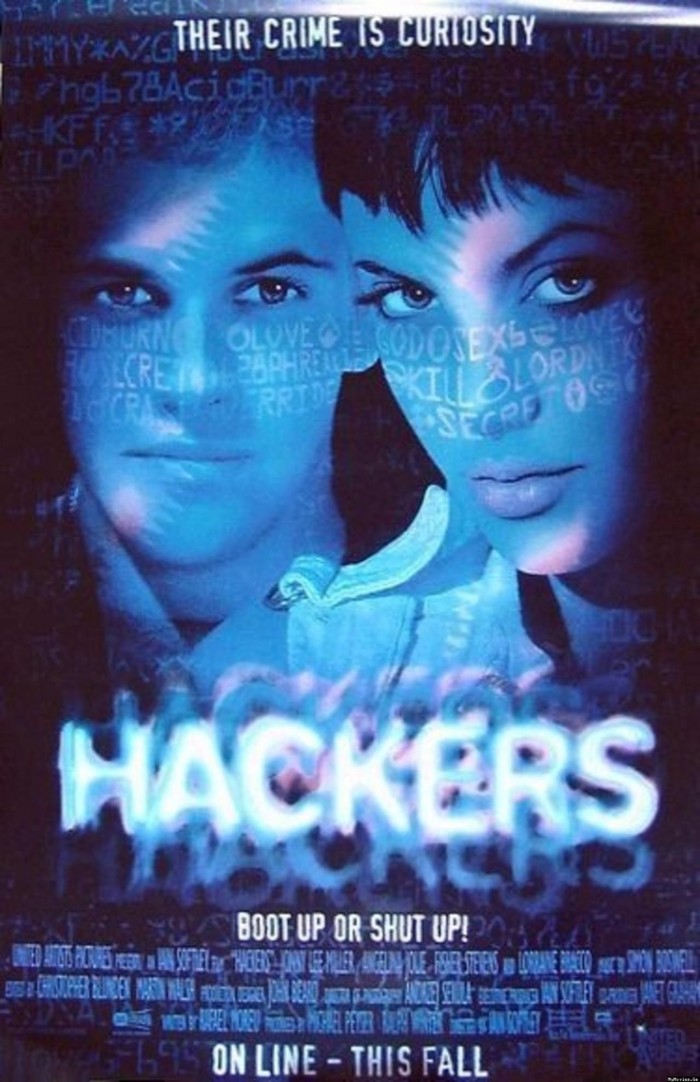

On September 15, 1995, MGM released a stylish, cyberspace thriller called Hackers. Two weeks later—following mixed reviews and poor box office numbers—the film was gone from theaters. Yet despite inauspicious start, Hackers has grown to become one of the most beloved films of the 90s. This is a story about the making of that movie and the ambitious filmmakers who, over time, have been vindicated by their hyperkinetic vision.

Hackers Oral History

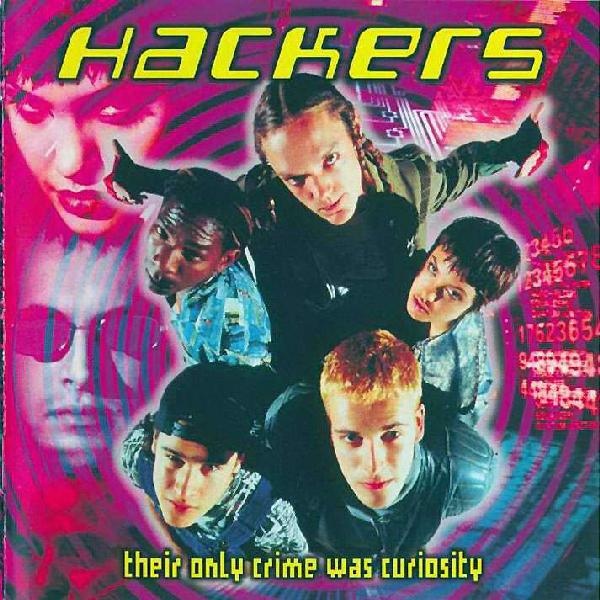

How Did This Get Made is a companion to the podcast How Did This Get Made with Paul Scheer, Jason Mantzoukas and June Diane Raphael. This regular feature is written by Blake J. Harris, who you might know as the writer of the book Console Wars, soon to be a motion picture produced by Seth Rogen and Evan Goldberg. You can listen to the Hackers edition of the HDTGM podcast here. Synopsis: After moving to New York, hacker Dade Murphy (aka "Crash Override") and his newfound posse of pals discover a plot to unleash a deadly digital threat—the so-called Da Vinci virus—and must use their computer skills to thwart the evil scheme.Tagline: Their Only Crime was Curiosity

In the latter half of 1995, at the dawn of the digital age, two films came out that dealt heavily with the notion of cyberspace: The Net (starring Speed-survivor Sandra Bullock) and Hackers (starring a then-unknown British actor). The Net grossed over $50 million domestically, while Hackers took in less than $10 million. Yet of the two, Hackers is the one that has withstood the test of time. Why, exactly, did this happen? And, more importantly, what can it tell us about the qualities that may help a movie age well?

Here's what happened, as told by those who made it happen...

Featuring:

PrologueIn the late 1980's, an executive from Paramount came to New York and checked into the Algonquin hotel on West 44th Street. Jeff Kleeman: Another executive from Paramount was staying across the street at The Royalton. It had just been remodeled and he said, "You gotta come in and take a look at this place; it's really cool looking." So I go into this vodka and champagne bar they had—where it kind of looked like anything you could sit on might hurt you—and I ordered a drink. The woman behind the bar, she was really nice, and we struck up a conversation. After chatting for a bit I had a dinner I had to get to, but before I left she said, "You know, if you have any free time in New York, I think you and my husband would really get along and we'd be happy to take you to lunch one day."Typically, this was not the kind of invitation that Kleeman—or most people, really—would accept. But, on that evening, there was something that piqued his interest. Jeff Kleeman: It was very bold, but it was also kind of lovely because the thing about living and working in Hollywood—which may be true of any industry—is it gets very insular. And if you're relatively young like I was, only a few years out of college, you start to feel like your world has shrunk. Instead of meeting people from all over the world—studying every subject imaginable and talking about anything under the sun—all of the sudden, for the past five or six years, all I talked about wasn't even movies. It was the movie business. So I thought: why not?Inspired by this unfamiliar burst of possibility, Kleeman agreed to have lunch with the couple a few days later. Little did he know that that this would not only blossom into an unexpected friendship, but it would eventually lead to an unusual movie called Hackers.

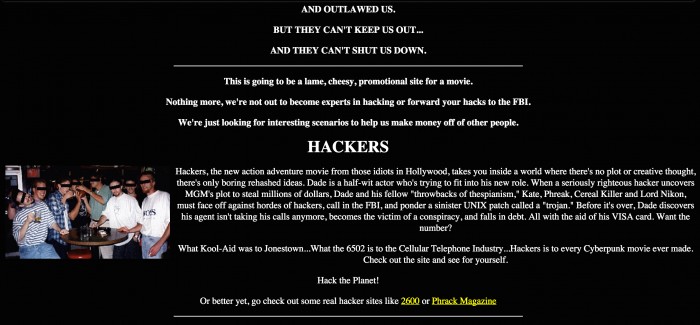

PrologueIn the late 1980's, an executive from Paramount came to New York and checked into the Algonquin hotel on West 44th Street. Jeff Kleeman: Another executive from Paramount was staying across the street at The Royalton. It had just been remodeled and he said, "You gotta come in and take a look at this place; it's really cool looking." So I go into this vodka and champagne bar they had—where it kind of looked like anything you could sit on might hurt you—and I ordered a drink. The woman behind the bar, she was really nice, and we struck up a conversation. After chatting for a bit I had a dinner I had to get to, but before I left she said, "You know, if you have any free time in New York, I think you and my husband would really get along and we'd be happy to take you to lunch one day."Typically, this was not the kind of invitation that Kleeman—or most people, really—would accept. But, on that evening, there was something that piqued his interest. Jeff Kleeman: It was very bold, but it was also kind of lovely because the thing about living and working in Hollywood—which may be true of any industry—is it gets very insular. And if you're relatively young like I was, only a few years out of college, you start to feel like your world has shrunk. Instead of meeting people from all over the world—studying every subject imaginable and talking about anything under the sun—all of the sudden, for the past five or six years, all I talked about wasn't even movies. It was the movie business. So I thought: why not?Inspired by this unfamiliar burst of possibility, Kleeman agreed to have lunch with the couple a few days later. Little did he know that that this would not only blossom into an unexpected friendship, but it would eventually lead to an unusual movie called Hackers.  Part 1: A Conversation with Phiber OptikDuring the late 80s and early 90s, Mark Abene was best known by the handle "Phiber Optik." Although only a teenager at the time, Phiber Optik was renowned as a world class hacker and a member of two famed hacking groups: The Legion of Doom and Masters of Deception. What follows is a condensed version of a conversation that took place between the two of us on November 23, 2015. Mark Abene: The thing you have to remember is that computer hacking in the US wasn't illegal until 1986. Prior to that, it was a great time to be an underground hacker; a great time to explore technology. It was something that not a whole lot of people did or even understood. A kid with a home computer and a modem could gain access to some pretty sophisticated stuff. From there, that kid was really only limited by his own imagination.Blake Harris: And for you, back then, what types of things captured your imagination?Mark Abene: Throughout the 80s, I kind of built up a reputation as, let's say, a guy who can get things done. Really adept at gaining access to systems, specializing in a lot of the internal administrative systems run by the phone company. It might sound crazy today, but we just had a ridiculous respect for the insane bureaucracy that the phone company had created. All the administrative systems and the switching systems that made the whole thing work. It was just this gargantuan network of systems and that it actually worked, and ran well, was just amazing to us. It was basically the largest computer network in the world. So we wanted to know everything about this thing. It was like a game, really. Like Dungeons and Dragons. There was a lingo, a special language that only phone employees understood, and if you could speak that lingo then it was like magical words and phrases.Blake Harris: You compare it to a game. But unlike a role-playing game or a videogame, there was not "victory," per se, or final level to what you were doing. So what was it that motivated you?Mark Abene: The way I try to explain it to people, sort of, is to think of it as the biggest adventure game you could ever imagine. Except it's real. And the things that you do in the game, they effect the real world. Not in any kind of life or death kind of way, but when you consider that we were basically kids—barely teenagers, growing up in the 80s—we had absolutely no voice in society and we expected that, any moment, we were going to die in a brilliant flash of light. And that was going to be, basically, the end of the world. It's the absolute truth.Blake Harris: As in a nuclear war?Mark Abene: Yeah. Anyone who grew up in the 80s knows what I'm talking about. It's the horrible thing we choose not to think about anymore. But it was everywhere—in our movies, in our music—and we were expecting that at some point, somebody was going to yell, "duck and cover" and that was going to be the end of that. So it was a really different kind of vibe going on. And online, the underground culture that we created was a society that we created for ourselves, that was separate from what was going on in the outside world. It was an escape from that.Blake Harris: And in this society, you went by Phiber Optik, right? That was your alias?Mark Abene: [laughing] No hacker ever referred to himself as having an alias; we weren't spies! We always referred to our alter egos as handles.Blake Harris: Ha, okay, gotcha. So as Phiber Optik, I'm curious to hear how you started meeting other people.Mark Abene: Do you mean online or in person?Blake Harris: I want to hear about online first.Mark Abene: Sure. So the first computer I got was a TRS-80. I had 4K of RAM. Not 4 gigs, not 4 megs, but 4K of RAM (which was not anything out of the ordinary back then). At first, I had no way to load or store things, so I'd try to keep the computer on for as long as possible, but ultimately I got a memory expansion—which gave me a total of 20K—and subsequent to that I got a cassette recorder for loading and storing programs. Floppy drives were pretty expensive, so the idea of using cassette tape drive was pretty popular. And then sometime after that, either for a Christmas or a birthday, I got the gift of a modem. A 300-baud modem...Blake Harris: And where did that allow you to go? The modem.Mark Abene: I mean, there was no Internet at all when I first got on dial-up. All throughout the 80s really. There were networks, obviously, but those networks were X25, packet-switch networks. They had similarities the Internet, but they were private. So by and large, most people who got modems had a trial account with CompuServe. That was the most common thing. You'd access that on dial-up and everything there was text-based—there was no graphics at all, naturally—and it was ridiculously expensive. Even by 1980s terms. It was a local phone call, but remember all phone calls were metered back then, so you were paying over ten cents a minute to be online in the first place and then on top of that CompuServe was charging something like $6 an hour to be online. So, as you can imagine, I was only on CompuServe for a couple of months. Luckily, within that span of time, I learned several things.Blake Harris: Like what?Mark Abene: I found out about BBS's, bulletin board systems [which, to oversimplify, were like private message boards] I started spending a lot of time on BBS's and was running up some questionably high phone bills. Since pretty much everyone else was in the same position, one of the first things you'd hear about on of these BBS's is people talking about how to get around that. These high phone bills. And that's kind of a rudimentary introduction to phone phreaking. And then from there, you start to learn about computer systems that you can dial into. Mini-computers and mainframes and so on and so forth.Blake Harris: When you'd dial into places s like that, how hard was it to get access?Mark Abene: In context, you kind of have to remember that some of these systems didn't have passwords. If you knew where to dial into and you dialed-in, then you were just there.Blake Harris: Okay, that makes sense.Mark Abene: But the thing that kind of goes along with that is that sooner or later you learn what it feels like when somebody changes a password on you. And you no longer have access to that thing that you really enjoyed accessing. And sooner or later you make a decision that you have to learn—and you don't even know what's it's called or what it really is—but what you have to learn is computer security. And how to circumvent it. And that's really how it begins; wanting to maintain access to whatever the cool thing is that you want to be accessing. For me it was originally mini-computers and mainframes where I could learn how to program and chat with other users and play text adventures on. That's really how it began.Blake Harris: And as you mentioned earlier, at this point you were only interacting with these people online. When did you start to actually meet some of them in person?Mark Abene: That was really a pivotal point that you're touching on. How do you go from, you know, being an underground hacker—known only by a handle and maybe by a first name to the people you trust most—to lifting the curtain and meeting people in real life? And meeting with these people, in public, when after 1986 the things that you're doing are ultimately illegal.Blake Harris: Exactly.Mark Abene: Well, a good sort of starting place was 2600 [referring to the magazine 2600: The Hacker Quarterly, founded by Eric Corley, best known by the name Emmanuel Goldstein]. Eric started the magazine in 1984 and then, I think it was 1986, he started having monthly meetings. I went to one of the first meetings and there were maybe five people there. And it was basically just the five of us, sitting at a table in a food court in the Atrium at Citccorp building [in New York City, on 53rd and Lex]. Everyone was super paranoid so it was pretty much just people whispering into each other's ears. I think I went to the first few and then stopped going to the meetings for a while. But around the close of the 80s and beginning of the 90s, when all of us started having our troubles with the law, that's when I basically decided to start making public appearances. And 2600 was a good rallying point initially.Blake: Why did you start making public appearances?Mark Abene: For me personally, it was really coming from a need to speak out. Because I was seeing friends of ours in New York, and guys in other states, who had gotten in trouble with the federal government. We were really concerned that if we didn't put forward some kind of image of our own, in our own words, somebody else would fill in the blanks and do the talking for us. And it wouldn't be somebody that we wanted to. Typically, as history has shown us, in the absence of reasonable explanation, you can expect some highly unreasonable agent of the government or federal prosecutor will make some ridiculous claims.Blake Harris: And I take you were not alone? By this point, there were more than five people showing up at the 2600 meetings?Mark Abene: Absolutely. By 1991, it was a madhouse. The meetings were still held in the Atrium at Citicorp—we'd meet on the first Friday of every month—but people were coming from all over the world to New York, so all kinds of people used to show up. And a lot of times media people would show up because they wanted a hot story.Blake Harris: Is that were you first met Rafael Moreu?Mark Abene: Rafael? Yeah. I remember one particular evening, Rafael showed up. He met me, Eric—you know, Emmanuel Goldstein—and several of our friends, and we went out to dinner in the east village after the meeting.Blake Harris: With so much at stake, especially around that time, what was it about Raphael that caused you to trust him?Mark Abene: He was an honest-to-goodness honest guy. Rafael was just one of those guys that you could read his face. And he understood what we were all about. He saw that we weren't a bunch of pencil-necks. That we were, for all practical intents and purposes, kind of a stylish bunch. Sure, we were highly opinionated, full of bravado, but that bravado was obviously backed up with smarts. Not only technological smarts, but street smarts. The bottom line is that he understood we were a social bunch. And so when he said he wanted to write a movie about us, we wanted to help him in any way we could.Blake Harris: How did that manifest? When Rafael started writing the script, which obviously became Hackers, what was that relationship like?Mark Abene: Oh, it was great. He'd come out with us when we went rampaging around the east village and he would invite us over to his house. We would hang out with him and his girlfriend. They lived together and at the time they had a small apartment in the east village. And we would just talk for hours, developing a lot of the story ideas. I mean, the thing that you gotta remember is we put a lot of in-jokes into the movie. Some things didn't make it in, but a lot of them did. You know, things that we thought were particularly funny that maybe other people didn't get.Blake Harris: Like what?Mark Abene: Literally all kinds of jokes. In the dialogue, plot devices. Everything from the flare gun thing to the fact that the villain was named The Plague. The Plague was actually a friend of ours, Yuri, who consulted with Rafael also. And I developed the whole idea of, see, the Exxon Valdez disaster had just happened—the oil barge had spilled in Alaska—so that was fresh in everyone's minds still. So one time when I was over at Rafael's house I said something like, "What if we had this plot device where a computer virus infects oil barges and causes them to topple and spill? And somehow that's what the hackers are trying to prevent?" So we developed that as like the main underlying part of the story.Blake Harris: That's great. Do you remember any other examples?Mark Abene: Oh yeah. The virus in the movie, you know, the main threat, we named it the "Da Vinci Virus" as a joke. That's because, just a little before this time, there had been a virus called Michelangelo that was in all the media. And John McAfee—from McAfee anti-virus fame—he was putting forth the latest virus propaganda that hackers had created this virus called Michelangelo that was a logic bomb and a time-bomb that was going to go off on such and such a time and it was, like, going to destroy everyone's hard-drive. And, of course, nothing ever happened. It was questionable whether or not the virus even existed at all.Blake Harris: That's hilarious.Mark Abene: Yeah. Exactly. Some things didn't make it in, but a lot of them did. And I don't remember how long it took, but we became friends with Rafael—we all took part in helping him develop—and I remember reading the final screenplay and thinking it was really cool. He had nailed it.Raphael Moreau, undoubtedly, was thrilled that those he was writing about found his work to be authentic and entertaining. But now, what he really needed, was someone else in the film business who felt that same way.

Part 1: A Conversation with Phiber OptikDuring the late 80s and early 90s, Mark Abene was best known by the handle "Phiber Optik." Although only a teenager at the time, Phiber Optik was renowned as a world class hacker and a member of two famed hacking groups: The Legion of Doom and Masters of Deception. What follows is a condensed version of a conversation that took place between the two of us on November 23, 2015. Mark Abene: The thing you have to remember is that computer hacking in the US wasn't illegal until 1986. Prior to that, it was a great time to be an underground hacker; a great time to explore technology. It was something that not a whole lot of people did or even understood. A kid with a home computer and a modem could gain access to some pretty sophisticated stuff. From there, that kid was really only limited by his own imagination.Blake Harris: And for you, back then, what types of things captured your imagination?Mark Abene: Throughout the 80s, I kind of built up a reputation as, let's say, a guy who can get things done. Really adept at gaining access to systems, specializing in a lot of the internal administrative systems run by the phone company. It might sound crazy today, but we just had a ridiculous respect for the insane bureaucracy that the phone company had created. All the administrative systems and the switching systems that made the whole thing work. It was just this gargantuan network of systems and that it actually worked, and ran well, was just amazing to us. It was basically the largest computer network in the world. So we wanted to know everything about this thing. It was like a game, really. Like Dungeons and Dragons. There was a lingo, a special language that only phone employees understood, and if you could speak that lingo then it was like magical words and phrases.Blake Harris: You compare it to a game. But unlike a role-playing game or a videogame, there was not "victory," per se, or final level to what you were doing. So what was it that motivated you?Mark Abene: The way I try to explain it to people, sort of, is to think of it as the biggest adventure game you could ever imagine. Except it's real. And the things that you do in the game, they effect the real world. Not in any kind of life or death kind of way, but when you consider that we were basically kids—barely teenagers, growing up in the 80s—we had absolutely no voice in society and we expected that, any moment, we were going to die in a brilliant flash of light. And that was going to be, basically, the end of the world. It's the absolute truth.Blake Harris: As in a nuclear war?Mark Abene: Yeah. Anyone who grew up in the 80s knows what I'm talking about. It's the horrible thing we choose not to think about anymore. But it was everywhere—in our movies, in our music—and we were expecting that at some point, somebody was going to yell, "duck and cover" and that was going to be the end of that. So it was a really different kind of vibe going on. And online, the underground culture that we created was a society that we created for ourselves, that was separate from what was going on in the outside world. It was an escape from that.Blake Harris: And in this society, you went by Phiber Optik, right? That was your alias?Mark Abene: [laughing] No hacker ever referred to himself as having an alias; we weren't spies! We always referred to our alter egos as handles.Blake Harris: Ha, okay, gotcha. So as Phiber Optik, I'm curious to hear how you started meeting other people.Mark Abene: Do you mean online or in person?Blake Harris: I want to hear about online first.Mark Abene: Sure. So the first computer I got was a TRS-80. I had 4K of RAM. Not 4 gigs, not 4 megs, but 4K of RAM (which was not anything out of the ordinary back then). At first, I had no way to load or store things, so I'd try to keep the computer on for as long as possible, but ultimately I got a memory expansion—which gave me a total of 20K—and subsequent to that I got a cassette recorder for loading and storing programs. Floppy drives were pretty expensive, so the idea of using cassette tape drive was pretty popular. And then sometime after that, either for a Christmas or a birthday, I got the gift of a modem. A 300-baud modem...Blake Harris: And where did that allow you to go? The modem.Mark Abene: I mean, there was no Internet at all when I first got on dial-up. All throughout the 80s really. There were networks, obviously, but those networks were X25, packet-switch networks. They had similarities the Internet, but they were private. So by and large, most people who got modems had a trial account with CompuServe. That was the most common thing. You'd access that on dial-up and everything there was text-based—there was no graphics at all, naturally—and it was ridiculously expensive. Even by 1980s terms. It was a local phone call, but remember all phone calls were metered back then, so you were paying over ten cents a minute to be online in the first place and then on top of that CompuServe was charging something like $6 an hour to be online. So, as you can imagine, I was only on CompuServe for a couple of months. Luckily, within that span of time, I learned several things.Blake Harris: Like what?Mark Abene: I found out about BBS's, bulletin board systems [which, to oversimplify, were like private message boards] I started spending a lot of time on BBS's and was running up some questionably high phone bills. Since pretty much everyone else was in the same position, one of the first things you'd hear about on of these BBS's is people talking about how to get around that. These high phone bills. And that's kind of a rudimentary introduction to phone phreaking. And then from there, you start to learn about computer systems that you can dial into. Mini-computers and mainframes and so on and so forth.Blake Harris: When you'd dial into places s like that, how hard was it to get access?Mark Abene: In context, you kind of have to remember that some of these systems didn't have passwords. If you knew where to dial into and you dialed-in, then you were just there.Blake Harris: Okay, that makes sense.Mark Abene: But the thing that kind of goes along with that is that sooner or later you learn what it feels like when somebody changes a password on you. And you no longer have access to that thing that you really enjoyed accessing. And sooner or later you make a decision that you have to learn—and you don't even know what's it's called or what it really is—but what you have to learn is computer security. And how to circumvent it. And that's really how it begins; wanting to maintain access to whatever the cool thing is that you want to be accessing. For me it was originally mini-computers and mainframes where I could learn how to program and chat with other users and play text adventures on. That's really how it began.Blake Harris: And as you mentioned earlier, at this point you were only interacting with these people online. When did you start to actually meet some of them in person?Mark Abene: That was really a pivotal point that you're touching on. How do you go from, you know, being an underground hacker—known only by a handle and maybe by a first name to the people you trust most—to lifting the curtain and meeting people in real life? And meeting with these people, in public, when after 1986 the things that you're doing are ultimately illegal.Blake Harris: Exactly.Mark Abene: Well, a good sort of starting place was 2600 [referring to the magazine 2600: The Hacker Quarterly, founded by Eric Corley, best known by the name Emmanuel Goldstein]. Eric started the magazine in 1984 and then, I think it was 1986, he started having monthly meetings. I went to one of the first meetings and there were maybe five people there. And it was basically just the five of us, sitting at a table in a food court in the Atrium at Citccorp building [in New York City, on 53rd and Lex]. Everyone was super paranoid so it was pretty much just people whispering into each other's ears. I think I went to the first few and then stopped going to the meetings for a while. But around the close of the 80s and beginning of the 90s, when all of us started having our troubles with the law, that's when I basically decided to start making public appearances. And 2600 was a good rallying point initially.Blake: Why did you start making public appearances?Mark Abene: For me personally, it was really coming from a need to speak out. Because I was seeing friends of ours in New York, and guys in other states, who had gotten in trouble with the federal government. We were really concerned that if we didn't put forward some kind of image of our own, in our own words, somebody else would fill in the blanks and do the talking for us. And it wouldn't be somebody that we wanted to. Typically, as history has shown us, in the absence of reasonable explanation, you can expect some highly unreasonable agent of the government or federal prosecutor will make some ridiculous claims.Blake Harris: And I take you were not alone? By this point, there were more than five people showing up at the 2600 meetings?Mark Abene: Absolutely. By 1991, it was a madhouse. The meetings were still held in the Atrium at Citicorp—we'd meet on the first Friday of every month—but people were coming from all over the world to New York, so all kinds of people used to show up. And a lot of times media people would show up because they wanted a hot story.Blake Harris: Is that were you first met Rafael Moreu?Mark Abene: Rafael? Yeah. I remember one particular evening, Rafael showed up. He met me, Eric—you know, Emmanuel Goldstein—and several of our friends, and we went out to dinner in the east village after the meeting.Blake Harris: With so much at stake, especially around that time, what was it about Raphael that caused you to trust him?Mark Abene: He was an honest-to-goodness honest guy. Rafael was just one of those guys that you could read his face. And he understood what we were all about. He saw that we weren't a bunch of pencil-necks. That we were, for all practical intents and purposes, kind of a stylish bunch. Sure, we were highly opinionated, full of bravado, but that bravado was obviously backed up with smarts. Not only technological smarts, but street smarts. The bottom line is that he understood we were a social bunch. And so when he said he wanted to write a movie about us, we wanted to help him in any way we could.Blake Harris: How did that manifest? When Rafael started writing the script, which obviously became Hackers, what was that relationship like?Mark Abene: Oh, it was great. He'd come out with us when we went rampaging around the east village and he would invite us over to his house. We would hang out with him and his girlfriend. They lived together and at the time they had a small apartment in the east village. And we would just talk for hours, developing a lot of the story ideas. I mean, the thing that you gotta remember is we put a lot of in-jokes into the movie. Some things didn't make it in, but a lot of them did. You know, things that we thought were particularly funny that maybe other people didn't get.Blake Harris: Like what?Mark Abene: Literally all kinds of jokes. In the dialogue, plot devices. Everything from the flare gun thing to the fact that the villain was named The Plague. The Plague was actually a friend of ours, Yuri, who consulted with Rafael also. And I developed the whole idea of, see, the Exxon Valdez disaster had just happened—the oil barge had spilled in Alaska—so that was fresh in everyone's minds still. So one time when I was over at Rafael's house I said something like, "What if we had this plot device where a computer virus infects oil barges and causes them to topple and spill? And somehow that's what the hackers are trying to prevent?" So we developed that as like the main underlying part of the story.Blake Harris: That's great. Do you remember any other examples?Mark Abene: Oh yeah. The virus in the movie, you know, the main threat, we named it the "Da Vinci Virus" as a joke. That's because, just a little before this time, there had been a virus called Michelangelo that was in all the media. And John McAfee—from McAfee anti-virus fame—he was putting forth the latest virus propaganda that hackers had created this virus called Michelangelo that was a logic bomb and a time-bomb that was going to go off on such and such a time and it was, like, going to destroy everyone's hard-drive. And, of course, nothing ever happened. It was questionable whether or not the virus even existed at all.Blake Harris: That's hilarious.Mark Abene: Yeah. Exactly. Some things didn't make it in, but a lot of them did. And I don't remember how long it took, but we became friends with Rafael—we all took part in helping him develop—and I remember reading the final screenplay and thinking it was really cool. He had nailed it.Raphael Moreau, undoubtedly, was thrilled that those he was writing about found his work to be authentic and entertaining. But now, what he really needed, was someone else in the film business who felt that same way.  Part 2: The Porousness of IdentityJeff Kleeman: So, going back to the woman at the bar—Kristin—we met up for lunch a couple days later and her husband was lovely. The three of us, we became great friends, and whenever I would come into New York I would see them. And I remember one year I even came in during Thanksgiving and they so generously invited me over for Thanksgiving dinner. And at a certain point, the husband, whose name was Rafael, he said, "I want to try my hand at writing and I've been working on a spec screenplay. Would you be willing to read it?" I said, "Sure." And, as you could probably guess, that script turned out to be Hackers.By this time, Kleeman had left Paramount and was now working for Francis Ford Coppola at American Zoetrope. Jeff Kleeman: After I finished reading Hackers, I was completely blown away. This was probably around 1992, at a time when we all kind of knew that there was this thing called "The Internet", but nobody was on it. And, of course, there had been no dealing with any of it. Now, the one thing that had preceded Hackers was War Games. And it's important because it does in some ways, for people like me, set the template. So War Games did exist. It was the one bit of popular culture that everyone of my generation knew that did exist. But War Games was not only a one-off, but War Games also kind of implied that there was this one sort of lone genius who happened to have this interest as opposed to the sense that there was an entire movement out there. And even an entire generation that was becoming aware and interested and starting to navigate the world in this way. And I think one of the things that was so exciting about Hackers was that it wasn't a loner. It was about a generation. And a new, in some ways, global way of navigating and thinking about what one could do with the world.Kleeman enthusiastically brought the script to Coppola, who loved it. Jeff Kleeman: So I got back to Rafael and Kristin and said, "Raf, I think you're a real writer and I think this is great. I think is a movie well worth making and in many ways an important movie to make. And I think it's perfect for us to produce." Raf said, "Great!" So I said, "Well, first things first, let's get you an agent." Because I was also fully aware, particularly for a first-time writer entering the business, that you never want someone to feel like they were taken advantage of later. Particularly in success. And not only was Raf a friend, but I genuinely believed he had a great career ahead of him. And I didn't want him to ever look back on this moment and think he was treated unfairly.Kleeman called up a friend at William Morris, which eventually led to Moreau meeting with one of their agent's in New York. She read the script, liked it and signed him. Jeff Kleeman: Shortly thereafter, I get a call from Rafael's new agent. She says, "So we've got an offer from another producer to option the script, do you want to counter?" I said, "What do you mean you've got an offer from the other producer? Since when have you been out shopping this to other producers?" I thought it was odd that she'd shown the script around, but we still wanted to buy it so I asked how much the other offer was so we could match it. "Well," she said, "I'm not going to tell you." So I said, "Wait a minute, you want me to counter against an offer for an amount that you won't share?" "Yeah," she said, "you make an offer and if it's greater than the offer that he's made; you'll get the script and if it's not than we'll sell it to him." I reminded her that we had brought William Morris this client and this project and reiterated that we certainly wanted to pay whatever was fair, but this seemed like a very one-sided negotiation; where she'd already decided on this other producer unless I happened to guess the right number. "Well," she said, "That's the way we're going to do it." So finally I just told her that if that was the case, then go with the other producer.Michael Peyser: I had been a producer in New York for many years before moving out to LA. Worked my way up from coffee, you know? Started in Sidney Lumet's crew... and I ended up working with a guy named Bob Greenhut, who was the consummate producer in New York; he did all the Woody Allen movies from Annie Hall on. And I became the production guy for Bobbie and Gordie Willis [director of photography] working with Woody. I did all the locations from Manhattan through, oh, Purple Rose of Cairo.After working on all those Woody Allen films, Peyser branched out and started producing movies of his own. Michael Peyser: What happened with Hackers was that Janet [Graham, a producer he worked with] had been reading about this kind of stuff from articles that people like Jack Hitt and others had written in the media. About the real kids who hung around the Citicorp Center. And the myth of the web. And the identity issues that were going to confront all of us as the porousness of identity and its protection/separation became ubiquitous. It was a profound thing. And I would say that the reason I made the movie and developed the whole thing was because I thought it was capable of containing that same dread that you felt watching The Conversation. Where while you're watching the movie your own sense of sanctity had evaporated entirely and you were raw naked and exposed to everybody. We set out to make a movie like that and, for two or three years, we spent time with these kids who hung out at Citicorp and really knew about the culture of the web.Jeff Kleeman: Some time passed and I don't remember the initial call or conversation, but someone reached out to me and said nothing had ever happened with this other producer and the option had expired. By now, we're probably in 1993 and I'm now over at MGM/United Artists. I'm working there an as executive. Even though a couple of years had passed I still felt the script was relevant. So when asked if I'd be interested in coming back on board I said, "Yeah, I believed it was a good script then and I believe it's a good script now. So absolutely I'd be interested. But under one condition: We will not negotiate with that particular agent." So Raf got a different agent at William Morris to work on his behalf. And John Calley, who was running United Artists at the time, he loved the script and he loved it for all the right reasons so we negotiated with a different agent this time and we were able to make a deal.Michael Peyser: I remained on as a producer, having developed the script, but after the deal with MGM I lost creative control entirely.The loss of creative control that Peyser is referring to—which can be typical in the transition from development to production, especially when options lapse—was less about diminishing his particular voice and more about empowering someone else's vision above all others. Kleeman and Calley believed that Hackers could be (and should be) a generation-defining movie—lending voice to a burgeoning revolution—and they wanted that voice to be amplified by a true auteur director.

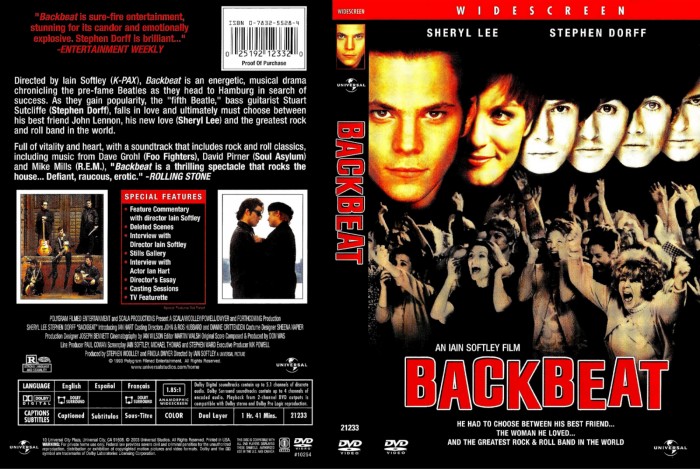

Part 2: The Porousness of IdentityJeff Kleeman: So, going back to the woman at the bar—Kristin—we met up for lunch a couple days later and her husband was lovely. The three of us, we became great friends, and whenever I would come into New York I would see them. And I remember one year I even came in during Thanksgiving and they so generously invited me over for Thanksgiving dinner. And at a certain point, the husband, whose name was Rafael, he said, "I want to try my hand at writing and I've been working on a spec screenplay. Would you be willing to read it?" I said, "Sure." And, as you could probably guess, that script turned out to be Hackers.By this time, Kleeman had left Paramount and was now working for Francis Ford Coppola at American Zoetrope. Jeff Kleeman: After I finished reading Hackers, I was completely blown away. This was probably around 1992, at a time when we all kind of knew that there was this thing called "The Internet", but nobody was on it. And, of course, there had been no dealing with any of it. Now, the one thing that had preceded Hackers was War Games. And it's important because it does in some ways, for people like me, set the template. So War Games did exist. It was the one bit of popular culture that everyone of my generation knew that did exist. But War Games was not only a one-off, but War Games also kind of implied that there was this one sort of lone genius who happened to have this interest as opposed to the sense that there was an entire movement out there. And even an entire generation that was becoming aware and interested and starting to navigate the world in this way. And I think one of the things that was so exciting about Hackers was that it wasn't a loner. It was about a generation. And a new, in some ways, global way of navigating and thinking about what one could do with the world.Kleeman enthusiastically brought the script to Coppola, who loved it. Jeff Kleeman: So I got back to Rafael and Kristin and said, "Raf, I think you're a real writer and I think this is great. I think is a movie well worth making and in many ways an important movie to make. And I think it's perfect for us to produce." Raf said, "Great!" So I said, "Well, first things first, let's get you an agent." Because I was also fully aware, particularly for a first-time writer entering the business, that you never want someone to feel like they were taken advantage of later. Particularly in success. And not only was Raf a friend, but I genuinely believed he had a great career ahead of him. And I didn't want him to ever look back on this moment and think he was treated unfairly.Kleeman called up a friend at William Morris, which eventually led to Moreau meeting with one of their agent's in New York. She read the script, liked it and signed him. Jeff Kleeman: Shortly thereafter, I get a call from Rafael's new agent. She says, "So we've got an offer from another producer to option the script, do you want to counter?" I said, "What do you mean you've got an offer from the other producer? Since when have you been out shopping this to other producers?" I thought it was odd that she'd shown the script around, but we still wanted to buy it so I asked how much the other offer was so we could match it. "Well," she said, "I'm not going to tell you." So I said, "Wait a minute, you want me to counter against an offer for an amount that you won't share?" "Yeah," she said, "you make an offer and if it's greater than the offer that he's made; you'll get the script and if it's not than we'll sell it to him." I reminded her that we had brought William Morris this client and this project and reiterated that we certainly wanted to pay whatever was fair, but this seemed like a very one-sided negotiation; where she'd already decided on this other producer unless I happened to guess the right number. "Well," she said, "That's the way we're going to do it." So finally I just told her that if that was the case, then go with the other producer.Michael Peyser: I had been a producer in New York for many years before moving out to LA. Worked my way up from coffee, you know? Started in Sidney Lumet's crew... and I ended up working with a guy named Bob Greenhut, who was the consummate producer in New York; he did all the Woody Allen movies from Annie Hall on. And I became the production guy for Bobbie and Gordie Willis [director of photography] working with Woody. I did all the locations from Manhattan through, oh, Purple Rose of Cairo.After working on all those Woody Allen films, Peyser branched out and started producing movies of his own. Michael Peyser: What happened with Hackers was that Janet [Graham, a producer he worked with] had been reading about this kind of stuff from articles that people like Jack Hitt and others had written in the media. About the real kids who hung around the Citicorp Center. And the myth of the web. And the identity issues that were going to confront all of us as the porousness of identity and its protection/separation became ubiquitous. It was a profound thing. And I would say that the reason I made the movie and developed the whole thing was because I thought it was capable of containing that same dread that you felt watching The Conversation. Where while you're watching the movie your own sense of sanctity had evaporated entirely and you were raw naked and exposed to everybody. We set out to make a movie like that and, for two or three years, we spent time with these kids who hung out at Citicorp and really knew about the culture of the web.Jeff Kleeman: Some time passed and I don't remember the initial call or conversation, but someone reached out to me and said nothing had ever happened with this other producer and the option had expired. By now, we're probably in 1993 and I'm now over at MGM/United Artists. I'm working there an as executive. Even though a couple of years had passed I still felt the script was relevant. So when asked if I'd be interested in coming back on board I said, "Yeah, I believed it was a good script then and I believe it's a good script now. So absolutely I'd be interested. But under one condition: We will not negotiate with that particular agent." So Raf got a different agent at William Morris to work on his behalf. And John Calley, who was running United Artists at the time, he loved the script and he loved it for all the right reasons so we negotiated with a different agent this time and we were able to make a deal.Michael Peyser: I remained on as a producer, having developed the script, but after the deal with MGM I lost creative control entirely.The loss of creative control that Peyser is referring to—which can be typical in the transition from development to production, especially when options lapse—was less about diminishing his particular voice and more about empowering someone else's vision above all others. Kleeman and Calley believed that Hackers could be (and should be) a generation-defining movie—lending voice to a burgeoning revolution—and they wanted that voice to be amplified by a true auteur director.  Jeff Kleeman: We saw a movie called Backbeat by Iain Softley. It was about the early years of The Beatles and been selected to screen at Sundance. I remember watching it in the screening room at United Artists and, similar to how I'd felt reading Rafael's script, I was blown away. In terms of a movie that talks about what it means to be of a specific generation—and in some ways representing a lot of the same ideas of Hackers—Backbeat was incredible. It was a very analogous movie, but utilizing music as opposed to technology.Michael Peyser: Jeff Kleeman and the others at MGM liked Backbeat. They asked me to see it. I saw it. We all had meetings and then an offer was made.Jeff Kleeman: John Calley called up Iain Softley's agent and my memory is that John offered not only a fair amount of money for a director who had never directed a studio movie [Backbeat was Softley's first film], but it was a pay-or-play deal. Meaning that if Iain wanted to make this movie, then we will make this movie. No Ifs, Ands or Buts.And to their great delight, Iain Softley very much wanted to make this movie.

Jeff Kleeman: We saw a movie called Backbeat by Iain Softley. It was about the early years of The Beatles and been selected to screen at Sundance. I remember watching it in the screening room at United Artists and, similar to how I'd felt reading Rafael's script, I was blown away. In terms of a movie that talks about what it means to be of a specific generation—and in some ways representing a lot of the same ideas of Hackers—Backbeat was incredible. It was a very analogous movie, but utilizing music as opposed to technology.Michael Peyser: Jeff Kleeman and the others at MGM liked Backbeat. They asked me to see it. I saw it. We all had meetings and then an offer was made.Jeff Kleeman: John Calley called up Iain Softley's agent and my memory is that John offered not only a fair amount of money for a director who had never directed a studio movie [Backbeat was Softley's first film], but it was a pay-or-play deal. Meaning that if Iain wanted to make this movie, then we will make this movie. No Ifs, Ands or Buts.And to their great delight, Iain Softley very much wanted to make this movie.  Part 3: Up the Lion's Mouth, a Fairy Tale Urban QuestIain Softley: Very soon after Backbeat was finished—almost before it was finished, I think—it was accepted to the Sundance Film Festival [where it would debut in January 1994]. But even before the premiere, in November and December, I was starting to get scripts from Hollywood. Which was quite a change in that nine months earlier I was trying to finish my first film and didn't know how it was going to turn out.Among the scripts that Softley received during that time was Hackers. Iain Softley: Unlike a lot of the other scripts that I was receiving, this one had the support of the head of the studio. John Calley, who was an iconic character because he had been an executive at Warner Brothers when they made a lot of the Stanley Kubrick films.Jeff Kleeman: You could do an entire year of podcasts and books on John Calley, who was one of the most amazing executives who's ever existed in Hollywood. He was fearless and not afraid to fail. And, you know, he had his flops; but he had his successes and success that no one else would have had. He exhibited great confidence in individuals. A complete side story but I brought in Leaving Los Vegas to United Artists and told him that I'd seen the movie and I thought for $1.5 million it would be a great deal. I said, "Do you want to see it?" And he said, "No. If you believe in it and you want to spend $1.5 million on it, go do it." So as an executive, you'd follow him to the ends of the earth. He empowered you. If he believed in you, in his gut, he'd roll the dice.Iain Softley: John was a very smart guy, very material-led. And Jeff Kleeman, who among other things, had the job of looking after the Bond movies for United Artists; he was the executive on Hackers. And he sent me the script by Rafael Moreau. I knew nothing about that world when I first read it, but I loved he energy. I loved the fun. And I especially loved the characters. And beyond those individual elements, it was skillful in the way that it combined a sort of fairy tale urban quest with this idea of the new frontier and the new world.Michael Peyser: These kids, these hackers, they just wanted to see how far up the lion's mouth they could stick their hand. They weren't really interested in malice. They were silver surfers. Explorers.

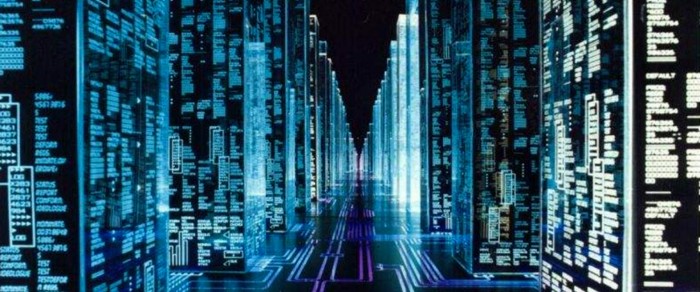

Part 3: Up the Lion's Mouth, a Fairy Tale Urban QuestIain Softley: Very soon after Backbeat was finished—almost before it was finished, I think—it was accepted to the Sundance Film Festival [where it would debut in January 1994]. But even before the premiere, in November and December, I was starting to get scripts from Hollywood. Which was quite a change in that nine months earlier I was trying to finish my first film and didn't know how it was going to turn out.Among the scripts that Softley received during that time was Hackers. Iain Softley: Unlike a lot of the other scripts that I was receiving, this one had the support of the head of the studio. John Calley, who was an iconic character because he had been an executive at Warner Brothers when they made a lot of the Stanley Kubrick films.Jeff Kleeman: You could do an entire year of podcasts and books on John Calley, who was one of the most amazing executives who's ever existed in Hollywood. He was fearless and not afraid to fail. And, you know, he had his flops; but he had his successes and success that no one else would have had. He exhibited great confidence in individuals. A complete side story but I brought in Leaving Los Vegas to United Artists and told him that I'd seen the movie and I thought for $1.5 million it would be a great deal. I said, "Do you want to see it?" And he said, "No. If you believe in it and you want to spend $1.5 million on it, go do it." So as an executive, you'd follow him to the ends of the earth. He empowered you. If he believed in you, in his gut, he'd roll the dice.Iain Softley: John was a very smart guy, very material-led. And Jeff Kleeman, who among other things, had the job of looking after the Bond movies for United Artists; he was the executive on Hackers. And he sent me the script by Rafael Moreau. I knew nothing about that world when I first read it, but I loved he energy. I loved the fun. And I especially loved the characters. And beyond those individual elements, it was skillful in the way that it combined a sort of fairy tale urban quest with this idea of the new frontier and the new world.Michael Peyser: These kids, these hackers, they just wanted to see how far up the lion's mouth they could stick their hand. They weren't really interested in malice. They were silver surfers. Explorers. Iain Softley: There's a very uplifting, human element to the story where these friends come together and support each other and fight the good fight. And for me, coming from Backbeat—which I wrote and directed—it was very important that whatever I directed next would allow me to bring some kind of creative vision to the project. And it seemed like there was a lot of scope in this. Because of the fact that a lot of what the story was about was taking place in an invisible world. You can't see data flying around cyberspace. So that, I realized, was giving me the chance to visualize aspects of the story, should I make that choice. Which I wanted to do, because in order to have the thrill of the chase, you need to be able to see the chase.Jeff Kleeman: So Iain read the script and responded to the material. Iain can be much more articulate about all the reasons he responded, but I remember him drawing an analogy to Backbeat where he basically referred to "their computers as their guitars."Iain Softley: From the moment I read the script, that similarity is what struck me. I said: okay, there's a parallel here because I've just made a movie that was set at the cusp of a cultural revolution. With Backbeat, I was looking in the past to do that. But with Hackers, I was sort of looking around the corner in the future, the near future.Jeff Kleeman: The whole process of the movie was in that spirit.Iain Softley: It was made very clear that John Calley and Jeff Kleeman wanted me to give Hackers the Backbeat treatment, in a way. And they wanted me to let my hair down creatively. So that was very appealing.Jeff Kleeman: One of my favorite moments, in terms of approach, came when we were talking about wardrobe. Iain said, "I want the cast to not dress the way that high school students dress today. I want them to dress however we predict they'd be dressing 15 seconds into the future."Iain Softley: What I used to say was that we needed to capture "the future just around the corner." I wanted us to anticipate what was ahead. So in that respect, there was almost a parallel reality element to the film; a hallucinogenic aspect. There were a lot of parallels, I thought, between these hackers and the ideals of the hippie generation. Stateless, unregulated freedom of movement. An exploration of new frontiers. And perhaps not surprisingly, a lot of the guys that were at the beginning of developing Internet technology, they had been going to Grateful Dead concerts. There was a symbiosis between those two countercultures. And I really picked that up and ran with it.

Iain Softley: There's a very uplifting, human element to the story where these friends come together and support each other and fight the good fight. And for me, coming from Backbeat—which I wrote and directed—it was very important that whatever I directed next would allow me to bring some kind of creative vision to the project. And it seemed like there was a lot of scope in this. Because of the fact that a lot of what the story was about was taking place in an invisible world. You can't see data flying around cyberspace. So that, I realized, was giving me the chance to visualize aspects of the story, should I make that choice. Which I wanted to do, because in order to have the thrill of the chase, you need to be able to see the chase.Jeff Kleeman: So Iain read the script and responded to the material. Iain can be much more articulate about all the reasons he responded, but I remember him drawing an analogy to Backbeat where he basically referred to "their computers as their guitars."Iain Softley: From the moment I read the script, that similarity is what struck me. I said: okay, there's a parallel here because I've just made a movie that was set at the cusp of a cultural revolution. With Backbeat, I was looking in the past to do that. But with Hackers, I was sort of looking around the corner in the future, the near future.Jeff Kleeman: The whole process of the movie was in that spirit.Iain Softley: It was made very clear that John Calley and Jeff Kleeman wanted me to give Hackers the Backbeat treatment, in a way. And they wanted me to let my hair down creatively. So that was very appealing.Jeff Kleeman: One of my favorite moments, in terms of approach, came when we were talking about wardrobe. Iain said, "I want the cast to not dress the way that high school students dress today. I want them to dress however we predict they'd be dressing 15 seconds into the future."Iain Softley: What I used to say was that we needed to capture "the future just around the corner." I wanted us to anticipate what was ahead. So in that respect, there was almost a parallel reality element to the film; a hallucinogenic aspect. There were a lot of parallels, I thought, between these hackers and the ideals of the hippie generation. Stateless, unregulated freedom of movement. An exploration of new frontiers. And perhaps not surprisingly, a lot of the guys that were at the beginning of developing Internet technology, they had been going to Grateful Dead concerts. There was a symbiosis between those two countercultures. And I really picked that up and ran with it. Part 4: The Great UnknownsIain Softley: I think at the center of the screen has to be a performer who you are just completely captivated by. Because once you become invested in those characters, it's kind of half the battle really. I mean you still have to create the world and the story and the environment within which those characters can take flight, but it's hugely important to get people who the audience is going to want to spend two hours with.Michael Peyser: I was involved with all the casting and that was fun. We worked with two casting directors: Michelle Guish, who is one of the greats in London, and Dianne Crittenden, who is one of the greats here (and had worked with Iain on Backbeat).Iain Softley: I did casting sessions in London, New York and Los Angeles. And it was in London that I found Jonny.

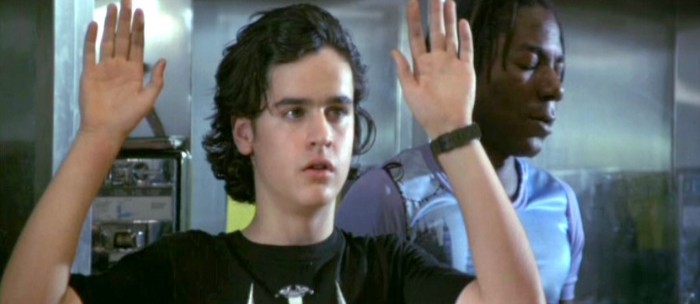

Part 4: The Great UnknownsIain Softley: I think at the center of the screen has to be a performer who you are just completely captivated by. Because once you become invested in those characters, it's kind of half the battle really. I mean you still have to create the world and the story and the environment within which those characters can take flight, but it's hugely important to get people who the audience is going to want to spend two hours with.Michael Peyser: I was involved with all the casting and that was fun. We worked with two casting directors: Michelle Guish, who is one of the greats in London, and Dianne Crittenden, who is one of the greats here (and had worked with Iain on Backbeat).Iain Softley: I did casting sessions in London, New York and Los Angeles. And it was in London that I found Jonny. Jonny, of course, is Jonny Lee Miller. Although Miller had never appeared in a feature film before, he had been appearing on stage and on BBC television shows since he was nine years old. For all involved it was quite clear that he was meant to play the role of Dade Murphy (aka "Crash Override"). But casting the female lead, who would play Miller's on-screen love interest, was a bit trickier. At least at first. Iain Softley: After we had narrowed it down, I took Jonny to New York and put him in combination with several of the callback actresses. Just to sort of look at the chemistry.Michael Peyser: We brought in lots of people...Jeff Kleeman: ...and we were very far down the line with a well-known actress whose name I won't mention because I don't want to hurt anyone's feelings. But basically it didn't matter after we got a tape from Dianne [Crittenden] of Jonny reading with Angelina. It was electrifying.

Jonny, of course, is Jonny Lee Miller. Although Miller had never appeared in a feature film before, he had been appearing on stage and on BBC television shows since he was nine years old. For all involved it was quite clear that he was meant to play the role of Dade Murphy (aka "Crash Override"). But casting the female lead, who would play Miller's on-screen love interest, was a bit trickier. At least at first. Iain Softley: After we had narrowed it down, I took Jonny to New York and put him in combination with several of the callback actresses. Just to sort of look at the chemistry.Michael Peyser: We brought in lots of people...Jeff Kleeman: ...and we were very far down the line with a well-known actress whose name I won't mention because I don't want to hurt anyone's feelings. But basically it didn't matter after we got a tape from Dianne [Crittenden] of Jonny reading with Angelina. It was electrifying. Iain Softley: It was incredible, the sparks that flew when they were in the room together. And when everybody saw the tapes, it was quite evident really that they were smoking hot on screen.Jeff Kleeman: None of us were surprised they got married after the movie ended, because in that first casting tape that chemistry was palpable. It was just riveting.Nevertheless, as riveting, electrifying and spark-inducing as Miller and Jolie may have been, casting the two would have meant that about 99.9% of potential moviegoers never would have heard of the stars of this movie. That's a big gamble. Iain Softley: Was I worried about that? No, I wasn't. The important thing is that you get people who are great. In Backbeat, I had cast Ian Hart—who wasn't really well known—but after the film came out he was taking everyone by storm because he was just so great. So I wasn't worried about that at all. But I could understand if Jeff and John had been looking for more bankable actors.Jeff Kleeman: I said to John, "I know casting this girl, Angelina Jolie, doesn't give us any marquee value whatsoever, but she's the better choice. These two people together, that's great cinema." And to John Calley's credit, he said, "You're right. Let's cast the unknown because she's the right one for the role." That may not sound like a big deal—to choose the best fit—but things like that are sadly a rarity in Hollywood.Iain Softley: It is to the eternal credit of Jeff and John that they backed me on the cast, and I was very grateful for their support. Thankfully, history seems to have proved all us right.

Iain Softley: It was incredible, the sparks that flew when they were in the room together. And when everybody saw the tapes, it was quite evident really that they were smoking hot on screen.Jeff Kleeman: None of us were surprised they got married after the movie ended, because in that first casting tape that chemistry was palpable. It was just riveting.Nevertheless, as riveting, electrifying and spark-inducing as Miller and Jolie may have been, casting the two would have meant that about 99.9% of potential moviegoers never would have heard of the stars of this movie. That's a big gamble. Iain Softley: Was I worried about that? No, I wasn't. The important thing is that you get people who are great. In Backbeat, I had cast Ian Hart—who wasn't really well known—but after the film came out he was taking everyone by storm because he was just so great. So I wasn't worried about that at all. But I could understand if Jeff and John had been looking for more bankable actors.Jeff Kleeman: I said to John, "I know casting this girl, Angelina Jolie, doesn't give us any marquee value whatsoever, but she's the better choice. These two people together, that's great cinema." And to John Calley's credit, he said, "You're right. Let's cast the unknown because she's the right one for the role." That may not sound like a big deal—to choose the best fit—but things like that are sadly a rarity in Hollywood.Iain Softley: It is to the eternal credit of Jeff and John that they backed me on the cast, and I was very grateful for their support. Thankfully, history seems to have proved all us right. In Jonny Lee Miller and Angelina Jolie, Hackers now had their two leads. But there were still several key roles to cast, particularly those who would join Miller and Jolie to round out the film's central group of friends/hackers: Cereal Killer, Phone Phreak and Joey. Jesse Bradford: I remember that when the audition came in for me, it was for Jonny Lee Miller's part. But when I read the script, I actually really responded to the Joey character. And I asked if I could read for him instead.Iain Softley: Jesse Bradford was fantastic. He was very young at the time [15 years old], but he had already done a couple of movies. Normally, when you're casting actors that young, what you're almost banking on is that they're not realizing they're acting. To capture that bubbly, bumbling energy. Getting them before they become too self-conscious. Whereas Jesse, while young, already had this great comic timing and great professionalism. He was able to convey so much; I was very impressed.Renoly Santiago: Jesse was so full of positive energy. Bursting with talent, wonder, intelligence, curiosity. Really wanting to make it happen; he was churning inside. He was only fifteen, I think, and his mom actually played his mom in the film.Jesse Bradford: [laughing] Yeah, that's one hundred percent true.Renoly Santiago: And his mom was a familiar face in commercials. I think she used to be in the Don't Squeeze the Charmin commercials, but you should confirm with Jesse.Jesse Bradford: My mom was an actress for many, many years and I had already gotten the part. And, you know, there's this role of my "Mom" in the movie, so I remember we were sitting around the dinner table one night, saying how funny it would be if my Mom played my Mom. So finally we said: hey, let's call my agent to see if they had any interest. So my Mom came in and read for the part...Renoly Santiago: How did I get the part? Well, before my actual audition—just for a little bit of trivia—the first time that I ever heard of the movie Hackers was when I auditioned for a casting director who has now passed away—rest in peace—her name was Mali Finn. She was casting the role of "Robin" for Batman and Robin. It was the second audition that I had gotten for that role and after we saw down to discuss Robin, she pulled out a script for Hackers. And I remember the cover was really cool: it had all this code on top of it. And then she was talking to me like I already had the part—of Phantom Phreak, "the king of Nynex"—like she was saying, "It's so great, you're talking on the phone, and you're all suave..." The part sounded really cool so she gave me a copy of the script to take home. I read it, but then a lot of time went by because they switched casting directors anyway.

In Jonny Lee Miller and Angelina Jolie, Hackers now had their two leads. But there were still several key roles to cast, particularly those who would join Miller and Jolie to round out the film's central group of friends/hackers: Cereal Killer, Phone Phreak and Joey. Jesse Bradford: I remember that when the audition came in for me, it was for Jonny Lee Miller's part. But when I read the script, I actually really responded to the Joey character. And I asked if I could read for him instead.Iain Softley: Jesse Bradford was fantastic. He was very young at the time [15 years old], but he had already done a couple of movies. Normally, when you're casting actors that young, what you're almost banking on is that they're not realizing they're acting. To capture that bubbly, bumbling energy. Getting them before they become too self-conscious. Whereas Jesse, while young, already had this great comic timing and great professionalism. He was able to convey so much; I was very impressed.Renoly Santiago: Jesse was so full of positive energy. Bursting with talent, wonder, intelligence, curiosity. Really wanting to make it happen; he was churning inside. He was only fifteen, I think, and his mom actually played his mom in the film.Jesse Bradford: [laughing] Yeah, that's one hundred percent true.Renoly Santiago: And his mom was a familiar face in commercials. I think she used to be in the Don't Squeeze the Charmin commercials, but you should confirm with Jesse.Jesse Bradford: My mom was an actress for many, many years and I had already gotten the part. And, you know, there's this role of my "Mom" in the movie, so I remember we were sitting around the dinner table one night, saying how funny it would be if my Mom played my Mom. So finally we said: hey, let's call my agent to see if they had any interest. So my Mom came in and read for the part...Renoly Santiago: How did I get the part? Well, before my actual audition—just for a little bit of trivia—the first time that I ever heard of the movie Hackers was when I auditioned for a casting director who has now passed away—rest in peace—her name was Mali Finn. She was casting the role of "Robin" for Batman and Robin. It was the second audition that I had gotten for that role and after we saw down to discuss Robin, she pulled out a script for Hackers. And I remember the cover was really cool: it had all this code on top of it. And then she was talking to me like I already had the part—of Phantom Phreak, "the king of Nynex"—like she was saying, "It's so great, you're talking on the phone, and you're all suave..." The part sounded really cool so she gave me a copy of the script to take home. I read it, but then a lot of time went by because they switched casting directors anyway. A couple months later, Santiago was brought in by Dianne Crittenden to audition for the role of Phantom Phreak. Renoly Santiago: I wanted him to be funny, you know? I saw there was funniness in the script. But he's really technical too, and really pushy with getting people together. How can I make this guy really snappy and edgy? So made him really New York and then there's thing that I kind of do where I slouch a little when I'm standing. That was the kind of posture that I gave him. Like: yeah, he's in high school, but he acts like he's running an empire or something. I wanted to make it ironic that he's so young, just beginning life, and that's how he acts. So I read that for her, it went well, fine. Then I got called in to meet Ian Softley and I do remember after reading the scene for him, for some reason when he started asking me general questions I took it as part of the audition. So what I did to stand out was I put my feet on his desk and crossed my legs while we did the interview. He didn't flinch, neither did the casting person. And then I left and then I was fortunate enough to get the part.Iain Softley: I just loved the street-talking humor that Renoly had. He had—and still has to this day—such a vibrant energy. He just fizzes on-screen.Renoly Santiago: I had been in one movie before Hackers—Dangerous Minds with Michelle Pfeifer—but, to me, getting the part in Hackers was just as big as the first. Cause it was like: okay, thank goodness, I got another one. I can do this. And also just being from a market that is still developing, which is being a Latino actor, there's not that wealth of opportunity out there. So when I do get something, I always get on my knees, you know? I thank God, I thank The Creator; it really does make you be grateful. And for me, it's sort of hard not to believe in a God when something like that, something that good, happens to you in life.

A couple months later, Santiago was brought in by Dianne Crittenden to audition for the role of Phantom Phreak. Renoly Santiago: I wanted him to be funny, you know? I saw there was funniness in the script. But he's really technical too, and really pushy with getting people together. How can I make this guy really snappy and edgy? So made him really New York and then there's thing that I kind of do where I slouch a little when I'm standing. That was the kind of posture that I gave him. Like: yeah, he's in high school, but he acts like he's running an empire or something. I wanted to make it ironic that he's so young, just beginning life, and that's how he acts. So I read that for her, it went well, fine. Then I got called in to meet Ian Softley and I do remember after reading the scene for him, for some reason when he started asking me general questions I took it as part of the audition. So what I did to stand out was I put my feet on his desk and crossed my legs while we did the interview. He didn't flinch, neither did the casting person. And then I left and then I was fortunate enough to get the part.Iain Softley: I just loved the street-talking humor that Renoly had. He had—and still has to this day—such a vibrant energy. He just fizzes on-screen.Renoly Santiago: I had been in one movie before Hackers—Dangerous Minds with Michelle Pfeifer—but, to me, getting the part in Hackers was just as big as the first. Cause it was like: okay, thank goodness, I got another one. I can do this. And also just being from a market that is still developing, which is being a Latino actor, there's not that wealth of opportunity out there. So when I do get something, I always get on my knees, you know? I thank God, I thank The Creator; it really does make you be grateful. And for me, it's sort of hard not to believe in a God when something like that, something that good, happens to you in life. Part 5: Computer Hacking 101Renoly Santiago: Before filming, first we had two weeks of rehearsal, which is kind of rare for a movie. It wasn't really rehearsal though, it was more learning how to rollerblade and learning about computers.Jesse Bradford: It was cool. I got the inside track on some stuff that people were only just getting hip to at the time.Jeff Kleeman: There was a point where in researching hackers I met with the secret service. And a lot of what they were saying at the time was essentially this: there are high school kids that know far more about this than any of us do.Jesse Bradford: So they brought in these real-life hackers to show us the ropes and teach us what they do a little. I mean, I didn't understand it real great, but I knew I was seeing something interesting going down.Mark Abene: I couldn't take part in any of that because I was actually in prison for a year when that was going on. But my friends Dave and Nick were active consultants.Dave Buchwald: My job description was basically to make the hackers and the hacking stuff as realistic as possible. But, you know, still fitting into the fantasy of the story and all that kind of stuff. I ended up working with the director and assistant director and coaching a bunch of the actors on, like, this is what hackers do and how they do it.Jesse Bradford: It was just kind of fun stuff. Like here's where to put your hands on the keyboard to look like you know what you're doing. The lingo, the concepts.Omar Wasow: I think part of the reason we got hired was...you know, this was still an era where the dominant image of techies was nerds and the idea that you could have somebody who was you know kind of a cool geek was still pretty novel. And so, at the risk of patting myself on the back, they saw an image of me with two feet of dreadlocks and thought: oh, like, this is someone who could talk to our actors and help us persuade them that this world of 1's and 0's is also one where there are people who would make sense to actors from Hollywood.Renoly Santiago: Omar was excellent! He's the guy that I remember most. He was this mixed-race guy with dreadlocks and kind of had this Rasta thing going on. So when I met Omar I was just like: Totally! I totally get it. Being an actor, I'm feeding off of feeling and energy and right away when I met him I got his vibe and I saw that he was a bohemian and everything. And he had the hair and I had the hair so I connected with him.Omar Wasow: One of the things is remember was trying to explain what a Pentium chip was to Angelina Jolie. Because, you know, how do you do that? Well, the way I try to explain any technology is with a real-world analogy or metaphor. It wasn't helpful to say "this is the central processing unit." But it sort of is helpful to say, "this is the brains of the computer and it's sort of the newest edition of the brain."Iain Softley: Omar became a great resource to us. And he became a liaison between myself and Neville Brody, our graphics designer in London. The graphics were being emailed overnight (as the script was being changed), and Omar very much helped us with the downloads and then with kind of road-testing the updated graphics and talking the actors through it.Dave Buchwald: I met with the principals a couple of times. They weren't exactly table reads, but they were like; gathered around, discussing the characters and things in the script. And then I met a bunch of times with Fisher Stevens who played The Plague, the lead bad guy. I met with him at his place a number of times. He very much wanted to get into character and was voraciously picking my brain. Reading tons of stuff.Renoly Santiago: They gave us some articles to read and also a book. Neuromancer by William Gibson. I remember Matthew Lillard really being into the book.