'Guardians Of The Galaxy Vol. 2' Is An Intimate Drama About Cycles Of Abuse...With A Talking Space Raccoon

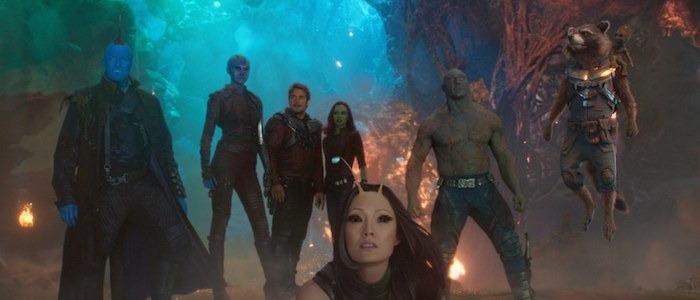

(Welcome to Road to Infinity War, a new series where we revisit the first 18 movies of the Marvel Cinematic Universe and ask "How did we get here?" In this edition: Guardians of the Galaxy Vol. 2 beautifully blends sci-fi craziness with an examination of anger, pain, and cycles of abuse.)Guardians of the Galaxy Vol. 2 is oodles of fun, but it spends its first few scenes articulating a thoughtful mission statement. Its prologue, set 34 years in the past, features a budding romance later revealed to have twisted implications, but the love on display is still real. Following this comes the Guardians' raucous reintroduction in present day, a battle against an inter-dimensional beast in a scene bursting with visual slepndour. Its out-of-this-world action however, is backgrounded and out of focus. The spotlight instead falls on a joyous Baby Groot, dancing his way through the scene as the other Guardians – Star Lord, Drax, Gamora and Rocket – take turns caring for him as if he were their child. When the Guardians collect their reward for this battle, they stand in contrast to the gilded Sovereign, a homogenous people genetically engineered to be perfect, but a people to whom slights and insults are unforgivable. The Guardians, on the other hand, are a group of broken characters from wildly different origins, but in their case, redemption isn't off the table.

In short, Guardians of the Galaxy Vol. 2 is about the complicated relationships we rarely confront. It's told against a backdrop of action and space-opera, but its focus is on a family of imperfect beings, searching for catharsis while helping one another other find some form of redemption. It may very well be Marvel's most mature film, zeroing in on the emotional complexities of abuse carried forward into adulthood. But it also solidifies the Studio's new political direction, acting as the first in a trilogy of films (along with Thor: Ragnarok and Black Panther) whose narrative is adjacent to colonial history.

Manifest Destiny

Once our Road to Infinity War reached Doctor Strange, it seemed the Marvel Cinematic Universe had begun re-orienting its perspective. Though what was previously subverted as narrative expectation vis-à-vis Western heroism now found itself the key focus, specifically in the form of Kurt Russell's villainous Ego a.k.a. The Living Planet. His plan, on the surface, is universal destruction, but the specifics of his scheme (and the ways in which he talks about his planting of literal and metaphorical seeds across the cosmos) bring to mind our Imperial past.

Ego doesn't just want to destroy our universe. He wants to conquer it. He is Manifest Destiny made, well, manifest, reflecting its very tenets in the context of Native American genocide while taking the form of a white man. He considers his colonial conquest to be 1) a function of his innate superiority, 2) a mission to remake the conquered in his own image, and 3) his universally-inspired destiny, with only his Celestial progeny deemed worthy of survival. His palace, like Odin's in Thor: Ragnarok, is a museum unto his own history, but the statues he uses to tell his story are filled with half-truths.

He did go out in search of other life. He did meet and fall in love with Meredith Quill, and he does in fact love his son. But he also found life itself, and the countless other children he fathered across the cosmos, to be disappointments. Since none of them shared his divinity, he considered them genetically inferior and unable to help him on his mission.

His gilded palace is build on a foundation of bones – that of the countless children he deemed unworthy and who, despite his love for them, were but a means to an end. When that end is threatened thanks to Peter, the first and perhaps only child with Ego's "superior" genetic traits, he vocalizes his disdainful justification. With the light that burns within them under threat, he reminds Peter of the consequences of snuffing it out: "You're a god. If you kill me, you'll be just like everybody else." It's this contempt for other beings, this unwillingness to value life and inability to recognize the potential for redemption, that makes Ego the perfect villain for this story; his colonial selfishness is the perfect foil to a future where characters reach across boundaries and help one another.

The flowers Ego planted across the universe begin to bloom. They start to consume and terraform vast array of planets and cultures, as if acting as externalizations of Ego's very self. Peter however, rejects immortality and Godhood itself, accepting the flaws and failures of the "everybody else" Ego would just as soon wipe out. Because even the mortals who have hurt Peter are still capable of empathy.

In this moment, Ego begins his quest to homogenize existence itself. But it's in this very moment that Peter taps in to the full potential of his own powers by recalling what separates him from Ego: love. Not unselfish or unconditional love, but love for Yondu, for Rocket, for Gamora and for all the Guardians; the kind of shared love that, over the course of Guardians Vol. 2, has proven to be difficult. And yet, the kind of love that Ego refuses to understand. The universe now depends on this understanding of love, because what hangs in the balance isn't just existence, but the opportunity to exist imperfectly together.

The Walls of the Broken

The Bradley Cooper-voiced Rocket, the trash-talking, gun-toting Raccoon, helps tie this film together. He rides the line between sarcasm and callousness, often crossing over into the latter when addressing Peter – "Orphan boy" is a hard jab to swallow, regardless of intent – which Peter rightly recognizes as Rocket's attempt to push people away. Once Rocket is separated from his crew, Michael Rooker's Yondu explains Rocket's self-sabotaging tendencies to him, because Yondu recognizes himself in the scrawny cybernetic mammal. They both felt used and discarded, Yondu by his parents who sold him into slavery, and Rocket by the scientists who tore him apart and put him back together, leading to the erecting of emotional walls nearly impossible to penetrate. Any amount of love or proximity to others reminds them of the holes in their hearts.

Yondu and Rocket hurt those closest to them before they have the opportunity to be hurt, but they come to a common understanding when Peter is about to sacrifice himself to save the universe. Yondu, having spent decades acting out against Peter – perhaps in ways that may be tormenting and abusive – finally comes to admit that he cares for him. Yondu kidnapped Peter when he was just a boy, but rather than delivering him to Ego like he was hired to, he kept Peter around. He trained Peter to be a Ravager, teaching him how to shoot and offering tender guidance even amidst threats that his crew would eat him if he didn't fall in line. A fatherly love marred by Yondu's own wounds, the kind that prevented him from loving fully and the kind of complicated love that Rocket had for Peter as well.

When Rocket sees Yondu go off to sacrifice himself to save Peter, he believes both men will perish for the greater good. When Gamora tries to go back to save Peter, Rocket stops her for her own safety. As Rocket becomes an inadvertent party to Peter's sacrifice, he finally realizes what he's about to lose: a friend.

It takes extreme circumstances for Rocket and Yondu to allow themselves to be vulnerable. When Yondu finally does, Peter is able to finally look up to him as the father figure he always was, despite Yondu arguably paying forward the abuse he himself was dealt as a child. Because ultimately, Yondu still sacrifices himself to save Peter. And, after having pushed away all the other Ravagers with his heinous actions – delivering Ego's children to him before knowing they'd be slaughtered – word of the disgraced Yondu's sacrifice reaches their ears. The Ravagers show up to Yondu's funeral despite the shame he caused them, as he redeems himself in death and proves to Rocket – on whom the film closes – that he's still capable of being loved.

Anger, Paid Foward

Yondu is one of three complicated, arguably abusive fathers in Guardians Vol. 2, but he's the only one who's redeemed in any sense. The second is Ego, whose genuine love is superseded by selfish desire. The third is never seen on screen, at least in this film, though we're likely to see the full scope of his paternal complications in Avengers: Infinity War. That third father is none other than Thanos, whose own quest for universal domination will bring him face to face with his adopted daughters. Despite Thanos' one prior on-screen appearance – three, if you count post-credits scenes – nothing about the Mad Titan was particularly fleshed out. That is, until his daughter Nebula (Karen Gillan) first speaks of why she resents him.

Guardians of the Galaxy is an odd franchise compared to its contemporaries. While going from one installment to the next, it turns not one, but two of its villains into empathic heroes. The first, Yondu, is a father who pays forward the same pain he was dealt, but ultimately leans towards love. He finds a shred of redemption through sacrifice, regardless of whether or not his past actions were forgiven – even Peter has a tough time articulating his feelings at Yondu's funeral.

The second former villain is Nebula, whose own story involves an abusive father (one potentially paying his pain forward as well), though a father for whom redemption seems out of the question. As children, Nebula and her sister Gamora (Zoe Saldana) were repeatedly set against one another in battle. The winner was hardened through survival. The loser had a body part replaced by machine. Gamora was usually the victor, with both daughters being molded into warriors regardless, but they were both also loyal to Thanos until the events of the first film – as their four siblings, The Black Order, appear to be in Infinity War.

Instead of rebelling against Thanos, one of the most powerful beings in the universe, Nebula and Gamora turned their resentment against one another as many abused siblings do. They see each other as the cause of their pain, and while they reconcile by the end of the film, both sisters (Nebula especially) seem to still be holding on to their anger. Though now, as they part ways, they have a better place to put that anger as they head off on their own roads to fighting Thanos.

The film never justifies the angry, occasionally violent ways in which the characters act out. Whether Yondu's threats to a vulnerable child, or Nebula continuously trying to kill Gamora, or Rocket's hurtful jabs. But it most certainly empathizes. James Gunn's superhero family saga understands the real-world complexities of parental love and abuse, things that, while far from ideal, often go hand in hand. They leave long-lasting emotional scars which can be hard to process, often resulting in anger directed elsewhere. Sometimes these abusive elements are hard to recognize when they're masked by love, like Ego's manipulation of Peter as they play catch for the first time. Sometimes genuine love is buried deep down beneath hardened, hypermasculine exteriors, like Yondu's refusal to open up to a boy he so clearly considered a son. Regardless of whether it should or shouldn't be, loving is often hard when the ways in which you've loved have caused you pain; cycles of violence and abuse can hurt us in ways that make us hurt those we care about. But it doesn't have to stay this way.

By the end of the film, the Guardians begin to recognize how they can be better. Drax learns to be kinder to Mantis, in his own way. Gamora learns to accept Nebula as her sister despite a violent past neither one can change. Rocket learns that he's still worthy of being loved despite his actions, and Peter even embraces a baby Groot to Cat Stevens' "Father and Son," having learned the complicated nature of the road ahead if he's to lead this family.

Guardians of the Galaxy Vol. 2 may be a weird, hilarious action movie filled to the brim with Marvel Easter Eggs – from The Watchers, to the "original" Guardians from the year 3000 to Howard The Duck – but it's grounded in the kind of human drama we rarely get to see in movies of any size. Rather than as metaphor, it tells direct stories of broken characters trying to be better together. Some of those characters are broken in ways familiar to us on this side of the screen, but the Guardians don't stay broken. The road to fixing themselves is a long one, a journey they've only just begun to take, but a journey they're taking it together.

The film is best summed up by its final shot: a close up on a trash-talking, gun-toting cybernetic Racoon, shedding a tear because he realizes that no matter how broken he is, and no matter how much he pushes people away, he'll still be loved at his funeral.