The 'Green Book' Controversy Explained: A Tour Of Hollywood's Long History Of Mishandling Black Stories

Green Book, starring Mahershala Ali as musical prodigy Dr. Don Shirley and Viggo Mortensen as bouncer-turned-actor Frank Anthony Vallelonga aka Tony Lip, just won Hollywood's biggest honor. But there are many moviegoers out there who are less than satisfied with Hollywood's love affair with the film. While Green Book has received support for being an entertaining look at an interracial friendship in the 1960s, many are also annoyed with the film focusing more on its white protagonist rather than its black one. It is Dr. Shirley, after all, who is taking a trip throughout the South and performing at prejudiced venues.The public's ire over Green Book has only intensified now that the film has won three Academy Awards, including Mahershala Ali for Best Supporting Actor, Peter Farrelly, Brian Currie and Nick Vallelonga (Lip's son) for Best Original Screenplay, and of course, Best Picture. Many are doing their best to separate Ali, an esteemed and beloved actor in his own right, from the mess surrounding Green Book. But it becomes hard to do that when the higher-ups surrounding the film, such as Vallelonga and Farrelly, went out of their way not to even acknowledge Shirley's life story during their acceptance speeches. Keep in mind that it is because of Shirley's life that the film even exists.It was assumed that Green Book, a film that has been called this century's Driving Miss Daisy, would probably win Best Picture because of its staid and reductive look at race relations. But even with that disappointing fact staring us in the face, I'm sure there are still people wondering why films like these are still getting made. Even though we are in a post-Black Panther and Hidden Figures world, even though the snubbed If Beale Street Could Talk seemed like a shoo-in for multiple Oscar nominations, why are films about race still hindered by Hollywood?In Green Book's case in particular, the question morphs into how could this film compound racial problems with a lack of due diligence as far as research is concerned. The film has been mired in so much controversy, especially when it comes to the feelings of Shirley's living family, who state that much of the film is false. In short, everything revolving around this film can be surmised in one quick question: How did this get made?Unfortunately, my deep dive into Hollywood's psyche surrounding race films and how it led to Green Book is a lot less funny than anything SlashFilm's HDTGM oral historian Blake Harris has had the privilege to unearth. Instead, I'm looking at Hollywood's obsession with the concepts of blackness and whiteness as constructs to manipulate and bend towards the will of the racial majority.

The first Hollywood race film

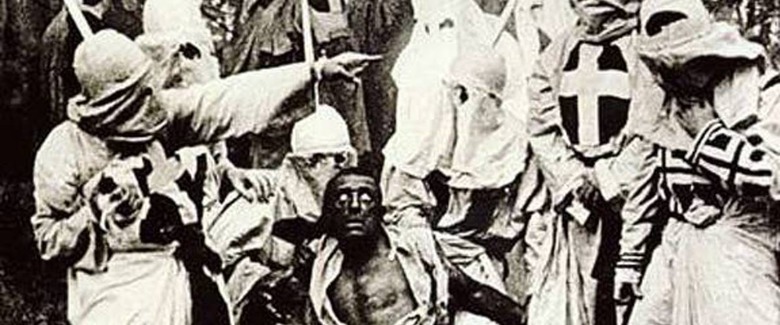

It shouldn't be a surprise to anyone that Hollywood keeps cranking out similar films about race over and over again. As much as Hollywood wants to be seen as a bastion of liberal thought, it's actually much more regressive in its views on race. To understand why Hollywood is still battling its regressiveness, it's important to know how Hollywood became mainstream. The first Hollywood blockbuster is 1915's Birth of a Nation by D.W. Griffith. The film is considered a technological landmark, utilizing techniques that would be replicated in many of the spectacle films from Hollywood's Golden Age. But apart from its status as an achievement in cinema, it also stands out as a love letter to the Ku Klux Klan.In this film, the Klan are positioned as literal white knights, protecting the South from the "scourge" of black people (men in particular). Blackness was seen as an epidemic that needed to be subdued, and the Klan, depicted as noble protectors of whiteness (especially when it came to white womanhood), were just the people to do the deed.The film's portrayal of blackness is all types of offensive. There are many white actors in blackface, but there are also actual black actors who played demeaning roles that supported the white supremacist message of the movie. In comparison to this and other issues, the blackface is probably the least of the film's problems regarding blackness.Almost every kind of stereotype surrounding blackness is employed, from the happy Mammy figure to the lustful, crazed black man. Black men in particular get it the worst; they are almost zombie-like in the film's portrayal, with the Klan acting as superheroes taking on the horde. In Birth of a Nation, black people are far from human. They're not even portrayed as animals. They're objects at best, and supernatural evil at worst. Birth of a Nation wants to be seen as an apocalyptic film, but instead of the apocalypse being a natural disaster or alien invasion, the apocalypse resides in the alleged sinfulness of black skin.This film is not only responsible for jumpstarting Hollywood, but it's also responsible for beginning the industry's backwards view of race. In many ways, Birth of a Nation simply highlighted society's already messed-up view of the black American. But the film also magnified those fears, entrenching them in how entertainment would tackle race from then on.

The seeds sown from Birth of a Nation

Ever since Birth of a Nation, Hollywood has internalized some stark stereotypes and tropes about how to relay stories about race. As time has gone on and as movements advanced black Americans, those tropes evolved. But they still functioned from the same concentration of white power in Hollywood.From Birth of a Nation, Hollywood came up with these tactics for films about race:

But how do these rules play out in films? Let's take a look at each one in depth.

White people in power getting to tell the narrative of blackness

Unfortunately, it's taken the bloodshed of many black men, women and children for Hollywood, much less the rest of the United States, to recognize that black people were, in fact, people. But even with the recognition that black Americans are owed their inalienable rights, films from the '60s all the way to the '00s were still largely created from a white point of view. Instead of empowering black filmmakers to tell their stories to a mainstream audience, white directors have been rewarded by making films about race that still center white feelings.For instance, recent films like 2009's The Blind Side, starring Sandra Bullock and Quinton Aaron, manipulated the true story of Michael Oher, a man who was taken in by a white family as teenager and went onto become an NFL superstar, into a white savior film. Bullock's character, Leigh Anne Tuohy, is portrayed as a woman who bravely goes beyond the colorlines to protect a black child from the wrong side of the tracks. It's positioned that it's her love and fortitude, not his talent, that lands him with a prime position in college football, his first rung in the ladder towards NFL stardom. We are invested more on Leigh Anne's humanity as a caring mother who is also a part of a white elite circle of Southern families than we are in Michael's humanity as a kid who has a broken family impacted by racial and social injustices. Even worse, the humanity of his mother (Adriane Lenox), a drug addict, is denied, despite the fact that her path toward drug use is partially due to racially-biased systems that proliferate drugs in some black neighborhoods. The Help, another recent film, is based on the 2009 book by Kathryn Stockett, who wrote in her author's notes that she based her book, essentially, around fan-fiction about her life. Raised in Mississippi, Stockett uses much of her life and her relationship to her family's maid Demetrie to inform her curiosity about what Demetrie would have said about her own life."I'm pretty sure I can say that no one in my family ever asked Demetrie what it felt like to be black in Mississippi, working for our white family. It never occurred to us to ask. It was everyday life. It wasn't something people felt compelled to examine," she wrote. "I have wished, for many years, that I'd been old enough and thoughtful enough to ask Demetrie that question. She died when I was sixteen. I've spent years imagining what her answer would be. And that is why I wrote the book."To her credit, Stockett does write that she doesn't presume to know what it's like to be a black woman. "I don't think it is something any white woman on the other end of a black woman's paycheck could ever truly understand," she wrote. "But trying to understand is vital to our humanity." And, if I'm being honest, I found The Help entertaining as a book. But as the years have gone on, I've thought more on the story and how it does a disservice to its black characters, even while doing its best to uplift them.First of all, even though the main characters are supposed to be maids Aibileen and Minny, the only person with any agency to change things is Skeeter, a white college-age girl who represents the author during her youth. Skeeter wants to write a book that makes a change, so she enlists the maids to tell their stories. But even the act of getting the maids onboard is one of white privilege; she doesn't understand how even speaking up in opposition could endanger the maids' already perilous lives. Instead, she seeks to know their story so her book can eventually be on the best-seller list. Their stories are supposed to enlighten readers, but they are also used as a tool to further Skeeter's career.Optics only get worse in the film version of the The Help, in which the film tries to rectify some of the maids' lack of agency. There's one particular scene that doesn't exist in the book – the final scene when Aibileen (Viola Davis) finally confronts her evil employer Miss Hilly (Bryce Dallas Howard) and quits. But even in this scene, one that's supposed to be triumphant, there is still whiteness at work.Tate Taylor, the writer-director of the film (and Stockett's longtime friend), had the right instinct to give Aibileen a "I'm mad as hell and I'm not going to take it anymore" type of scene. But after she quits, the audience is left with a lot of questions, some of which might have been answered if a black writer or a writer with more awareness of black Southern life were at the helm.It's naive to think that Aibileen could just quit her job in Mississippi during a time when there weren't a ton of opportunities for upward mobility for black southerners. The idea of quitting could be an option for a white maid, because they could easily go into the city to find upstanding work. But what could Aibileen, an uneducated black woman, do? She'd have to go from one menial job as a maid to another, possibly as a janitor, or more likely, a maid for some other white woman.Let's not forget that even though Aibileen quit, she still doesn't have the upper hand. Hilly still does, and she can still ruin Aibileen's life by spreading the lie around town that Aibileen is disobedient and hard to work with. Who would hire Aibileen then? How would she be able to make a living? The only other option would be to work in Skeeter's family's house, and even if she's working for a "nice" white family, she's still working for a white family.The Help also engages in another sin of Hollywood race films; the tropes of the "nice" white person and the "evil" white person. In this case, Skeeter is seen as the character folks who consider themselves progressive non-racists can attach themselves to. She is the fantasy many white people want to view themselves as; the person who, if the opportunity called for it, would rise to the occasion and stand up for oppressed people.Meanwhile, Hilly is the person white audiences recognize as the worst parts of themselves; the part that will go along with the status quo, the white patriarchal systems that have been in place in this country since its inception, as long as it works out to their advantage. This opportunistic construct of whiteness overlooks the plight and exploitation of others because there are schools of thought in place to separate whiteness from the guilt of perpetuating slavery, subjugation, and abuse.The white characters of The Help represent the propensity for Hollywood to insert tropes of whiteness. The working theory Hollywood seems to have is that white audiences cannot bear to be told about how knowingly and unknowingly participate in racist social structures. The guilt, it would seem, would be too much for the conscience to handle. Therefore, Hollywood has created tropes of whiteness that both assuage and remove the pain and trauma of guilt from its audience. These tropes can be seen in films throughout Hollywood's history.

The Help, another recent film, is based on the 2009 book by Kathryn Stockett, who wrote in her author's notes that she based her book, essentially, around fan-fiction about her life. Raised in Mississippi, Stockett uses much of her life and her relationship to her family's maid Demetrie to inform her curiosity about what Demetrie would have said about her own life."I'm pretty sure I can say that no one in my family ever asked Demetrie what it felt like to be black in Mississippi, working for our white family. It never occurred to us to ask. It was everyday life. It wasn't something people felt compelled to examine," she wrote. "I have wished, for many years, that I'd been old enough and thoughtful enough to ask Demetrie that question. She died when I was sixteen. I've spent years imagining what her answer would be. And that is why I wrote the book."To her credit, Stockett does write that she doesn't presume to know what it's like to be a black woman. "I don't think it is something any white woman on the other end of a black woman's paycheck could ever truly understand," she wrote. "But trying to understand is vital to our humanity." And, if I'm being honest, I found The Help entertaining as a book. But as the years have gone on, I've thought more on the story and how it does a disservice to its black characters, even while doing its best to uplift them.First of all, even though the main characters are supposed to be maids Aibileen and Minny, the only person with any agency to change things is Skeeter, a white college-age girl who represents the author during her youth. Skeeter wants to write a book that makes a change, so she enlists the maids to tell their stories. But even the act of getting the maids onboard is one of white privilege; she doesn't understand how even speaking up in opposition could endanger the maids' already perilous lives. Instead, she seeks to know their story so her book can eventually be on the best-seller list. Their stories are supposed to enlighten readers, but they are also used as a tool to further Skeeter's career.Optics only get worse in the film version of the The Help, in which the film tries to rectify some of the maids' lack of agency. There's one particular scene that doesn't exist in the book – the final scene when Aibileen (Viola Davis) finally confronts her evil employer Miss Hilly (Bryce Dallas Howard) and quits. But even in this scene, one that's supposed to be triumphant, there is still whiteness at work.Tate Taylor, the writer-director of the film (and Stockett's longtime friend), had the right instinct to give Aibileen a "I'm mad as hell and I'm not going to take it anymore" type of scene. But after she quits, the audience is left with a lot of questions, some of which might have been answered if a black writer or a writer with more awareness of black Southern life were at the helm.It's naive to think that Aibileen could just quit her job in Mississippi during a time when there weren't a ton of opportunities for upward mobility for black southerners. The idea of quitting could be an option for a white maid, because they could easily go into the city to find upstanding work. But what could Aibileen, an uneducated black woman, do? She'd have to go from one menial job as a maid to another, possibly as a janitor, or more likely, a maid for some other white woman.Let's not forget that even though Aibileen quit, she still doesn't have the upper hand. Hilly still does, and she can still ruin Aibileen's life by spreading the lie around town that Aibileen is disobedient and hard to work with. Who would hire Aibileen then? How would she be able to make a living? The only other option would be to work in Skeeter's family's house, and even if she's working for a "nice" white family, she's still working for a white family.The Help also engages in another sin of Hollywood race films; the tropes of the "nice" white person and the "evil" white person. In this case, Skeeter is seen as the character folks who consider themselves progressive non-racists can attach themselves to. She is the fantasy many white people want to view themselves as; the person who, if the opportunity called for it, would rise to the occasion and stand up for oppressed people.Meanwhile, Hilly is the person white audiences recognize as the worst parts of themselves; the part that will go along with the status quo, the white patriarchal systems that have been in place in this country since its inception, as long as it works out to their advantage. This opportunistic construct of whiteness overlooks the plight and exploitation of others because there are schools of thought in place to separate whiteness from the guilt of perpetuating slavery, subjugation, and abuse.The white characters of The Help represent the propensity for Hollywood to insert tropes of whiteness. The working theory Hollywood seems to have is that white audiences cannot bear to be told about how knowingly and unknowingly participate in racist social structures. The guilt, it would seem, would be too much for the conscience to handle. Therefore, Hollywood has created tropes of whiteness that both assuage and remove the pain and trauma of guilt from its audience. These tropes can be seen in films throughout Hollywood's history.  For instance, let's look at Quentin Tarantino's 2012 film Django Unchained. The film is supposed to be about Django (Jamie Foxx) and his search for his enslaved wife (Kerry Washington). Dr. King Schultz (Christoph Waltz) is supposed to be Django's mentor/sidekick, meaning he's supposed to be a supporting character. But instead, Tarantino's white guilt heavily informs Schultz as a character – he's uncommonly innocent about American racism and feels more empathy than even Django does about Django's predicament. Schultz even delivers the decisive blow to sadistic slaveowner Calvin Candie (Leonardo DiCaprio), the act Django was supposed to carry out. Also: his name is Dr. King, for goodness' sake. He's named after Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

For instance, let's look at Quentin Tarantino's 2012 film Django Unchained. The film is supposed to be about Django (Jamie Foxx) and his search for his enslaved wife (Kerry Washington). Dr. King Schultz (Christoph Waltz) is supposed to be Django's mentor/sidekick, meaning he's supposed to be a supporting character. But instead, Tarantino's white guilt heavily informs Schultz as a character – he's uncommonly innocent about American racism and feels more empathy than even Django does about Django's predicament. Schultz even delivers the decisive blow to sadistic slaveowner Calvin Candie (Leonardo DiCaprio), the act Django was supposed to carry out. Also: his name is Dr. King, for goodness' sake. He's named after Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

While Schultz is a cartoon of a white guilt, Candie and the KKK members in Django are cartoons of racist white people. They are uncommonly evil, disregarding the fact that many racists of the past and today are everyday people, including your neighbors. The film, like many before and after it, wrongly assert that racism is something that only exists in the extreme. Quite the contrary; throughout history, the most racist people have been the ones who were seen as those working for the common good. Scientists, doctors, politicians, next door neighbors, townspeople – anyone from any of these groups could be as racist as any KKK member. Racism exists the best within the grey areas of life; you don't need to have a white hood to be proud in ignorance.

Annoyingly, even Spike Lee's recent film, BlacKkKlansman, participates in these tropes. Ron Stallworth (John David Washington) is supposed to be the lead of the film, but he is often overshadowed by Flip Zimmerman (Adam Driver). Some of this is because of the nature of the story – Stallworth is tricking the KKK over the phone, but Zimmerman, a white cop, has to show up to the meetings. However, some of it is also because of the audience Lee is trying to pull. BlacKkKlansman may be a film marketed as one telling a black experience, but it is largely a film for the white audience. It's informing them about the elements of racism, stuff many black people already know about. It coddles the white audience by showing Stallworth's story through the experiences of Zimmerman, who has to grapple with his own minority status as a Jewish man.Zimmerman is BlacKkKlansman's "good" white person trope in contrast to the KKK members in the film, who are mostly portrayed as country, backwoods idiots. They are portrayed as the dregs of society, obvious to anyone who sees them, but when has racism always made itself known in such an aggressive fashion? Again, racism in film is displayed in the extreme, not where it usually lives, which is in the grey areas of life. It's in this gray area that black people face the most pernicious problems. Dr. King, in fact, said it best in his Letter from Birmingham Jail:

Annoyingly, even Spike Lee's recent film, BlacKkKlansman, participates in these tropes. Ron Stallworth (John David Washington) is supposed to be the lead of the film, but he is often overshadowed by Flip Zimmerman (Adam Driver). Some of this is because of the nature of the story – Stallworth is tricking the KKK over the phone, but Zimmerman, a white cop, has to show up to the meetings. However, some of it is also because of the audience Lee is trying to pull. BlacKkKlansman may be a film marketed as one telling a black experience, but it is largely a film for the white audience. It's informing them about the elements of racism, stuff many black people already know about. It coddles the white audience by showing Stallworth's story through the experiences of Zimmerman, who has to grapple with his own minority status as a Jewish man.Zimmerman is BlacKkKlansman's "good" white person trope in contrast to the KKK members in the film, who are mostly portrayed as country, backwoods idiots. They are portrayed as the dregs of society, obvious to anyone who sees them, but when has racism always made itself known in such an aggressive fashion? Again, racism in film is displayed in the extreme, not where it usually lives, which is in the grey areas of life. It's in this gray area that black people face the most pernicious problems. Dr. King, in fact, said it best in his Letter from Birmingham Jail:

"I have almost reached the regrettable conclusion that the Negro's great stumbling block in the stride toward freedom is not the White Citizens Councillor or the Ku Klux Klanner but the white moderate who is more devoted to order than to justice; who prefers a negative peace which is the absence of tension to a positive peace which is the presence of justice; who constantly says, 'I agree with you in the goal you seek, but I can't agree with your methods of direct action'; who paternalistically feels that he can set the timetable for another man's freedom; who lives by the myth of time; and who constantly advises the Negro to wait until a 'more convenient season.'"

Tropes like these are something I expect from Hollywood in general, but they are hardest to swallow from someone like Lee, who has made it his mission to create films that tell multifaceted stories of black life. Seeing Lee devolve to these cartoony methods of storytelling is frustrating.I'll end this section with this: Before anyone gets bent out of shape, I'm not saying every white person is bad. But even with me having to write this statement, I'm participating in the same white supremacist system that begs non-white people to soften or ignore their feelings about their lived-in reality. Not every white person is a bad person. Not every white person is a racist. But as a whole, white people benefit from the racist construct of whiteness. Its ill-gotten beneficial power is why whiteness is a construct that remains powerful to this day. Hollywood's inability or unwillingness to reckon with this power, the same power that helped build Hollywood, unfortunately keeps fueling the fire.

White people imagining blackness

Ever since Birth of a Nation, Hollywood's view of race has been from the viewpoint of whiteness. Even though Hollywood's Golden Age provided us with classics such as Rear Window, Psycho, The Wizard of Oz and An American in Paris, it's also indulged in its share of racial stereotypes.America's internal propaganda has relied strongly on the false narratives about black people and blackness as construct. Of course, it would have to be this way if slavery – legal human trafficking – was to become an intrinsic economic tool for a new nation.The lies told about black people have been immense and long-lasting in their power. Some of the most popular lies include black people being thought of as innately criminal, sexually repugnant, animalistic, infantile, mules of the world, jezebels, etc. These lies have persisted because they have been passed down from one white generation to the next, some of whom are also power players in America's upper echelon, such as the political sphere, economic sphere, and of course, the entertainment sphere.All the ways white people in power have used stereotypes against black people have hurt in more ways than you can imagine. But the one that I'd argue is the most insidious is how they are used in entertainment. Whereas film and TV are often thought of as a safe space for the imagination to believe in the impossible, that same playground is where America's collective imagination about blackness can explore its nightmarish beliefs on a grand scale. Storytelling has the power to inform us about ourselves and each other, and if the stories we receive tell us a certain group are terrible, we are more likely to believe it, especially if that message comes in the form of a pretty package like a film or TV show.Black audiences have had to endure injustice done to Hattie McDaniels, who had to play a Mammy character in Gone with the Wind. They've had to see themselves in countless actors playing childlike maids and butlers who are grateful to their white masters. They've had to grapple with blackface numbers by Al Jolson-starrer The Jazz Singer, Judy Garland-starrer Everybody Sing, and even Fred Astaire (one of my favorite old Hollywood stars) in what he thought at the time was a loving tribute to his tap-dancing idol, Bill "Bojangles" Robinson. Blackness has always been something to consume or exaggerate, not something to actually understand and respect.

Unfortunately, blackface is something that even continued in the 1980s, with 1986's Soul Man, a strange film starring C. Thomas Howell as Mark Watson, an affluent white teen who pretends to be a black kid in order to receive a college scholarship. This is a film Hollywood no longer talks about, with good reason. First, it's poking fun at affirmative action. Second, there's the visible problem of a white man wearing blackface. That, combined with his reason for doing so, doubles down on the white imagination's perversion of black life, including the idea that it is easier to be black because of perceived government kickbacks. This idea disregards the real reason affirmative action was installed – to help black students and employees gain access to opportunities once only given to their white counterparts. By engaging in blackface and black stereotypes, the film reasserts how the construct of blackness supersedes the reality of multifaceted, human experiences of the black diaspora. Black life is something that can be worn like a mask or a costume just to achieve an end.The Help, as I brought up before in this article, is another instance of blackness being reimagined in the white imagination. As Stockett has said herself, the book is an extension of her idea of what her black housekeeper could have said about her life. Some might decry the book as using Stockett appropriating her dead nanny's voice for her own personal gain, a type of literary blackface, if you will.There's also the very real case against Stockett's use of blackness for personal gain. According to ABC News, Ablene Cooper, a black nanny who worked in Stockett's brother's home, filed a $75,000 lawsuit against Stockett. She alleges that Stockett engaged in "unauthorized appropriation of her name and image" and says Stockett's brother and wife agree with her. Certainly, the names "Ablene" and "Aibileen" are too close for comfort, and Cooper alleges that Stockett knew about her after she babysat Stockett's daughter. She says that "she had been assured by Stockett...that her likeness would not be used in the book."The appropriation argument against the film is something the Association of Black Women Historians brings up in their open letter."The Help's representation of these women is a disappointing resurrection of the Mammy – a mythical stereotype of black women who were compelled, either by slavery or segregation, to serve white families," they wrote. "Portrayed as asexual, loyal and contented caretakers of whites, the caricature of Mammy allowed mainstream America to ignore the systemic racism that bound black women to back-breaking, low paying jobs where employers routinely exploited them.""...Both versions of The Help also misrepresent African American speech and culture," the association continued. "Set in the South, the appropriate regional accent gives way to a child-like, over-exaggerated, 'black' dialect. In the film, for example, the primary character, Aibileen, reassures a young white child that, ;You is smat, you is kind, you is important.' In the book, black women refer to the Lord as the 'Law,' an irreverent depiction of black vernacular."They also write about how black men were let down by the film by being portrayed as drunk abusers. "...We do not recognize the black community described in The Help where most of the black male characters are depicted as drunkards, abusive, or absent. Such distorted images are misleading and do not represent the historical realities of black masculinity and manhood," they wrote.

Black people are blocked from access

So why have films that tell race from the privileged point of view been lauded in Hollywood? Why do black filmmakers sometimes have to make films that soften the truth in order to achieve mainstream success? It's because Hollywood's racial power structure is still in play. That not only means that white directors have more of a chance of having their race films taken seriously, it also means that black directors, directors who have the lived experience of racism often don't have the access or connections they need to get their vision off the ground. If they do attain access, they still have to adhere to Hollywood's strange rules about race in order to get their films in the theaters.For instance, let's look at Miles Ahead, released in 2015. Don Cheadle is a recognizable Hollywood name and the star of more than a few major hits, so you'd think that it would be easy for Cheadle to get a movie about jazz legend Miles Davis made. But Cheadle lamented about how difficult it was to get funding from studios, resorting to an Indiegogo campaign and his own coffers. The only way he could get the movie off the ground with studios, he said, according to Tambay A. Obenson for IndieWire, was to add a white protagonist."There is a lot of apocryphal, not proven evidence that black films don't sell overseas," he said during the Berlin Film Festival press conference. "Having a white actor in this film turned out to actually be a financial imperative." The results of forcing in a white character plus financial concerns was a film that was lesser than what Cheadle actually wanted to make. Even films made by white directors and producers have run into roadblocks when it comes to films about race. Red Tails, the 2012 film telling the story of the Tuskegee Airmen, had a tough road to the theater despite being produced by George Lucas. The Star Wars creator told Jon Stewart during an interview on The Daily Show that studios didn't want to finance the film because they felt that there would be no market for a film with a mostly-black cast."They don't believe there's any foreign market for it and that's 60 percent of their profit," he said, according to The Hollywood Reporter. "...I showed it to all of them and they said, 'No. We don't know how to market a movie like this.'"He also said another roadblock came up because the film didn't have a white savior. Lucas used the example of 1989's Civil War film Glory, which starred Denzel Washington and Matthew Broderick. Even though Washington's character's story is much more important, it's Broderick's character that's central, fulfilling the "good white person" stereotype and keeping the focus of the film solely around white emotions towards black pain."It's an all-black movie. There's no major white roles in it at all," he said about Red Tails. "It's one of the first all-black action pictures ever made. It's not Glory where you have a lot of white officers running these guys into cannon fire. They were real heroes."How race films are rewarded boil down to racial stereotypes and tropes as well. There are many examples I could draw from: Halle Berry winning for her role as a downtrodden woman who falls in love with a racist in 2001's Monster's Ball, Denzel Washington's role as a detective-turned-bad in 2001's Training Day, Octavia Spencer's role as Minny in The Help, Whoopi Goldberg as a comedic psychic in 1990's Ghost, etc. In fact, it's worth noting that Goldberg somehow won an award for a nothing role in Ghost while being blocked out of the Oscars for her transcendent performance in 1985's The Color Purple.But what I want to discuss at length is one of the OG moments of the Oscars awarding black roles that demean rather than uplift – Sidney Poitier winning for his role in 1963's Lillies of the Field instead of his performance in 1961's A Raisin in the Sun or 1967's In the Heat of the Night.

Even films made by white directors and producers have run into roadblocks when it comes to films about race. Red Tails, the 2012 film telling the story of the Tuskegee Airmen, had a tough road to the theater despite being produced by George Lucas. The Star Wars creator told Jon Stewart during an interview on The Daily Show that studios didn't want to finance the film because they felt that there would be no market for a film with a mostly-black cast."They don't believe there's any foreign market for it and that's 60 percent of their profit," he said, according to The Hollywood Reporter. "...I showed it to all of them and they said, 'No. We don't know how to market a movie like this.'"He also said another roadblock came up because the film didn't have a white savior. Lucas used the example of 1989's Civil War film Glory, which starred Denzel Washington and Matthew Broderick. Even though Washington's character's story is much more important, it's Broderick's character that's central, fulfilling the "good white person" stereotype and keeping the focus of the film solely around white emotions towards black pain."It's an all-black movie. There's no major white roles in it at all," he said about Red Tails. "It's one of the first all-black action pictures ever made. It's not Glory where you have a lot of white officers running these guys into cannon fire. They were real heroes."How race films are rewarded boil down to racial stereotypes and tropes as well. There are many examples I could draw from: Halle Berry winning for her role as a downtrodden woman who falls in love with a racist in 2001's Monster's Ball, Denzel Washington's role as a detective-turned-bad in 2001's Training Day, Octavia Spencer's role as Minny in The Help, Whoopi Goldberg as a comedic psychic in 1990's Ghost, etc. In fact, it's worth noting that Goldberg somehow won an award for a nothing role in Ghost while being blocked out of the Oscars for her transcendent performance in 1985's The Color Purple.But what I want to discuss at length is one of the OG moments of the Oscars awarding black roles that demean rather than uplift – Sidney Poitier winning for his role in 1963's Lillies of the Field instead of his performance in 1961's A Raisin in the Sun or 1967's In the Heat of the Night.

Most of Poitier's roles involve showcasing black dignity, and his roles as Det. Tibbs in In the Heat of the Night and Walter Lee Younger in A Raisin in the Sun exemplify that. I'd argue that his role as Walter is the most significant performance of his career, because his character, while still dignified, had his dignity drowned in despair and broken by white supremacy. He showcased the grief that accompanies the black experience in America, and he showcased that grief in such a raw and unfiltered way that the Academy clearly wasn't ready for.Meanwhile, Lilies of the Field features Poitier playing a stereotypical role of a black man who spends the entire film doing chores for white nuns. Poitier's character, Homer Smith, is a handyman and former soldier who feels lost; we are to believe he finds his purpose once again when he comes across the nuns and starts rebuilding their church. His usefulness comes down to the fact that he's strong and resilient, the same types of things black men were exploited for during the slavery and sharecropping eras.It's this film that gets Poitier the Oscar for Best Actor. Part of this is because the Academy is notorious for giving actors awards for lesser films as an apology for not awarding them for the roles they should have won for. But Poitier was also able to win because his role as a handyman fit in with Hollywood's limited idea of what blackness can be. Finally, Poitier was playing a role in service to white people, and for that, the Academy felt comfortable awarding him.

How Green Book falls into the same traps

Green Book is clearly a film that's enjoyable to watch – there's a reason why the film has a 93 percent audience rating on Rotten Tomatoes, not to mention the 79 percent fresh rating from critics. But the film has still rubbed many the wrong way for falling into the same traps many other Hollywood films about race have fallen into.First of all, the film is from Tony's point of view instead of Dr. Shirley's. The decision to tell the story from Tony's point of view is the work of writer-director Farrelly and Vallelonga. But with a story that includes The Negro Motorist Green Book, a book written by black mailman Victor Hugo Green specifically for black Americans traveling throughout the country, you'd think Green Book would have black lives at its center. Instead, many critics have complained about white fragility is still at the heart of this film. The movie is all about Tony's journey toward recognizing black humanity.Some critics didn't hold back on their disgust with the film."The new movie Green Book sets up, with a pristine precision, a scenario that was already ridiculous when it was presented in Guess Who's Coming to Dinner, more than half a century ago: the acceptance by white people of a black protagonist whose talents and achievements are exceptional, whose manners are elegant, whose record is spotless, and whose résumé and connections are stamped 'high class,'" wrote The New Yorker's Richard Brody."...Green Book is perfectly adequate for what it is: middlebrow Oscar bait that plays it as safe as can be," wrote Inkoo Kang for Slate. "We get much too little about Donald's feelings about performing at mansions, including former plantations, filled with white people who worship his talents yet treat him as beneath them...We're also cheated out of learning about his relationships to other black people, other than the obvious complaint that he's thought of as 'not black enough.'"Dr. Shirley's family have also come out against the film, saying that it mischaracterizes Dr. Shirley and his relationship with his family."There was no due diligence done to afford my family and my deceased uncle the respect of properly representing him, his legacy, his worth and the excellence in which he operated and the excellence in which he lived," said Carol Shirley Kimble, Dr. Shirley's niece, to 1A Movie Club in a voicemail. "It's once again a depiction of a white man's version of a Black man's life. My uncle was an incredibly proud man and an incredibly accomplished man, as are the majority of people in my family. And to depict him as less than, and to depict him and take away from him and make the story about a hero of a white man for this incredibly accomplished Black man is insulting, at best." The family has also come out more forcefully against the film's lack of research in a comprehensive interview by Shadow and Act's Brooke Obie. In the interview, various family members call the film anything from "a symphony of lies" to "100 percent wrong."The film asserts that Shirley was estranged from his family because of his sexuality as well as black culture, two things his living family members refute with personal anecdotes to picture evidence. For instance, Shirley was his youngest brother Maurice's best man at his wedding. He stopped one of his musical tours to attend a nephew's untimely funeral. He took his other nephew, Edwin, on tour with him for nine days as they traversed Cincinnati and Chicago. The family also asserts that, unlike what the film suggests, Shirley and Vallelonga were never friends; it was only a professional relationship.When Nick Vallelonga, Tony Vallelonga's son, was shopping around the idea for a movie based on his father and Shirley's travels, Shirley continuously refused to give his blessing because he felt a film would never get his life story correct. At the time, Edwin said he was trying to convince his uncle to take the opportunity, but now, he says he completely understands his uncle's reticence."God knows, this is the reason that he never wanted to have his life portrayed on screen," Edwin told Obie. "I now understand why, and I feel terrible that I was actually trying to urge him to do this in the 1980s, because everything that he objected to back then has come true now."Since the film's release, Mahershala Ali has apologized to the Shirley family, saying he wasn't made aware that Shirley's family was still around to tell his story. The family believes Ali was misled.In our opinion," said Maurice to Essence's Britni Danielle, "[Ali]'s been duped.""We are very proud of him," Shirley's sister-in-law and Maurice's wife Patricia Shirley said of Ali."In no way would we ever steal his joy for his recognition because he is an accomplished actor and we respect his ability and his position." She added that they aren't "angry or vindictive;" instead, she said, they are "disappointed" with the film.Mortensen has yet to make such amends; instead, he believes the Vallelonga family are being patient throughout the controversy, as if they are true victims."[Writer] Nick Vallelonga has shown admirable restraint in the face of some accusations and some claims –including from a couple of family members – that have been unjustified, uncorroborated and basically unfair, that have been countered by other people who knew Doc Shirley well," he said to Variety's Marc Malkin. "There is evidence that there was not the connection that [the family members] claimed there was with him, and perhaps there's some resentment."

The family has also come out more forcefully against the film's lack of research in a comprehensive interview by Shadow and Act's Brooke Obie. In the interview, various family members call the film anything from "a symphony of lies" to "100 percent wrong."The film asserts that Shirley was estranged from his family because of his sexuality as well as black culture, two things his living family members refute with personal anecdotes to picture evidence. For instance, Shirley was his youngest brother Maurice's best man at his wedding. He stopped one of his musical tours to attend a nephew's untimely funeral. He took his other nephew, Edwin, on tour with him for nine days as they traversed Cincinnati and Chicago. The family also asserts that, unlike what the film suggests, Shirley and Vallelonga were never friends; it was only a professional relationship.When Nick Vallelonga, Tony Vallelonga's son, was shopping around the idea for a movie based on his father and Shirley's travels, Shirley continuously refused to give his blessing because he felt a film would never get his life story correct. At the time, Edwin said he was trying to convince his uncle to take the opportunity, but now, he says he completely understands his uncle's reticence."God knows, this is the reason that he never wanted to have his life portrayed on screen," Edwin told Obie. "I now understand why, and I feel terrible that I was actually trying to urge him to do this in the 1980s, because everything that he objected to back then has come true now."Since the film's release, Mahershala Ali has apologized to the Shirley family, saying he wasn't made aware that Shirley's family was still around to tell his story. The family believes Ali was misled.In our opinion," said Maurice to Essence's Britni Danielle, "[Ali]'s been duped.""We are very proud of him," Shirley's sister-in-law and Maurice's wife Patricia Shirley said of Ali."In no way would we ever steal his joy for his recognition because he is an accomplished actor and we respect his ability and his position." She added that they aren't "angry or vindictive;" instead, she said, they are "disappointed" with the film.Mortensen has yet to make such amends; instead, he believes the Vallelonga family are being patient throughout the controversy, as if they are true victims."[Writer] Nick Vallelonga has shown admirable restraint in the face of some accusations and some claims –including from a couple of family members – that have been unjustified, uncorroborated and basically unfair, that have been countered by other people who knew Doc Shirley well," he said to Variety's Marc Malkin. "There is evidence that there was not the connection that [the family members] claimed there was with him, and perhaps there's some resentment." Not only is that uncouth (to say the least), but it's a statement that re-centers the film around whiteness and white privilege instead of around Shirley's experience as a minority living within a prejudiced system. The focus for Mortensen and the film is the rehabilitation of whiteness for a white audience, not an exploration of the racist systems in place that both embolden white ignorance and perpetuate black pain.This becomes even more apparent now that a new controversy has surfaced; Nick himself has become the center of allegations of anti-Muslim sentiment, including his agreement with a false anti-Muslim rumor from Donald Trump.

Not only is that uncouth (to say the least), but it's a statement that re-centers the film around whiteness and white privilege instead of around Shirley's experience as a minority living within a prejudiced system. The focus for Mortensen and the film is the rehabilitation of whiteness for a white audience, not an exploration of the racist systems in place that both embolden white ignorance and perpetuate black pain.This becomes even more apparent now that a new controversy has surfaced; Nick himself has become the center of allegations of anti-Muslim sentiment, including his agreement with a false anti-Muslim rumor from Donald Trump.

So here we are, still reeling from the Best Picture win awarded to Green Book. Once again, it appears as if blackness and black experiences are reimagined and appropriated to tell a story Hollywood loves to tell over and over; the story of the black American, but through the white American's eyes. Like the Shirley family, we all should be disappointed that Shirley's life story was railroaded to continue the American tradition of white privilege in storytelling. Hopefully one day, the entertainment world decides to rid itself of this fairy tale once and for all.