The Patchwork Families Of Pixar: 'Finding Nemo' Turns 15

(Welcome to The Disney Discourse, a recurring feature where Josh Spiegel discusses the latest in Disney news. He goes deep on everything from the animated classics to the theme parks to live-action franchises. In this edition: Finding Nemo turns 15 and it represents much of what Pixar has spent the past few decades trying to say about families.)

Over nearly 25 years, Pixar Animation Studios has become the high watermark of American animation. Unlike even Walt Disney Animation Studios, which has had some level of creative and behind-the-scenes upheaval over more than eight decades, Pixar's films have been consistently successful with audiences and at the box office. Technologically and creatively, Pixar's filmmakers have made plenty of leaps from the first computer-animated feature, Toy Story, to last year's Coco.

Although the settings of these stories vary, Pixar has thematically been laser-focused for many years on telling stories about the creation and embrace of a community; it's an idea that is perhaps reflected most strongly of all in a film celebrating its 15th anniversary this month: Finding Nemo.

The Neuroses of Parenthood

Being a father doesn't pose the same challenges as being a mother, but even for the nebbishy clownfish Marlin (voiced brilliantly by Albert Brooks), the debilitating neuroses of being a parent are impossible to overcome. In the film's opening scene, before disaster strikes, Marlin asks his wife Coral, of the hundreds of their fish eggs waiting to hatch, "What if they don't like me?" (Few lines of dialogue in Pixar's filmography are so deft in establishing a character like that one.) Once Coral and all but one of the hatchlings are killed and eaten by a barracuda, Marlin becomes the worst kind of helicopter parent, even if it's for understandable reasons. By the time his only son Nemo is old enough to go to school, the familiar dynamic between parent and child is reversed: Marlin wants to stay home because he's terrified of what the rest of the ocean holds, whereas Nemo is champing at the bit to get out of the anemone.

Andrew Stanton, who co-wrote and directed Finding Nemo, used the film's commentary track to discuss how his own experiences as a parent influenced the creation of his first directorial effort. Within the context of the movie, Marlin's refusal to let his son be independent manages to be both frustrating and completely reasonable. (In earlier versions of the script, as Stanton describes on the film's commentary, the story begins with Nemo's first day of school and intersperses flashbacks throughout the film to that fateful day where Marlin lost almost everything. It's easy to see how that version would have made Marlin a lot less likable in the early going. It's also fascinating that Stanton went to the flashback well in both John Carter and Finding Dory to build emotion, but that's a discussion for a different column.)

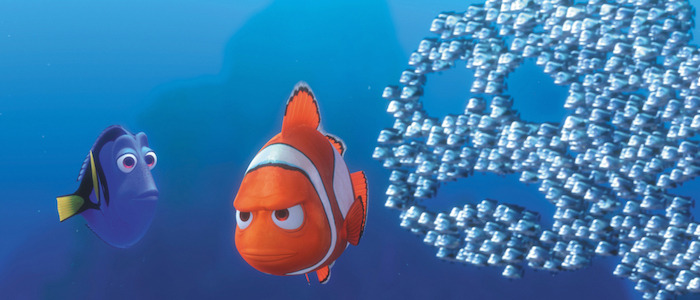

Once Nemo is taken away from Marlin, by a diver who works as a dentist in Sydney, Australia, the neurotic clownfish is on the hunt for his son with a charmingly forgetful blue tang named Dory (Ellen DeGeneres), essentially acting as a father to the childlike fish who gloms onto Marlin and won't let go. As exciting as the adventure is, it's a lengthy lesson for Marlin to realize that his understandably protective nature is going to cause his son to actually hate him and not just say it in a moment of frustration.

The same neuroses that led to Stanton making this story — he mentions on the commentary that he was able to identify how overprotective he was being towards his own son, to the point where he realized during an outing that he was squandering a possible father-son bonding moment — can be found in a lot of Pixar's films. Finding Nemo was the first to make it textual, as opposed to subtextual, but both before and after the 2003 hit, Pixar's storytellers (or at least their directors) have been basically obsessed with making parental foibles a central focus of the films they make.

A Recurring Trend

Fan theories about the true identity of Andy's mom aside, the Toy Story trilogy depicts the toys in his bedroom as something akin to a group of surrogate parental figures. (At the very least, Woody's specific neuroses about losing Andy in Toy Story 2 and Toy Story 3 are awfully similar to that of a father losing his grip on his child. And don't forget, we never learned about the identity of Andy's father in the Toy Story films, so hey, maybe the spirit of Andy's dead dad resides in a pull-string cowboy doll! Connect the dots.) The 2001 film Monsters, Inc. is a rollicking action adventure, but it's also a depiction of how a gruff male character becomes a father figure in a short period of time to a little girl. John Goodman's Sulley very quickly starts talking about the human girl "Boo" like his own daughter, not a terrifying alien interloper that terrifies all monsters.

The film after Finding Nemo, The Incredibles, is also squarely about the value of family. Writer/director Brad Bird has talked before about how his own struggles, trying to balance being a husband and father with being an animator/director on projects such as The Simpsons and The Iron Giant, impacted the design and construction of the 2004 superhero story. Granted, the family theme would be easy to spot even without Bird's admission, considering that a suburban family unit all with superpowers must join together to stop a nefarious bad guy. What's more, as the first hour of the film demonstrates, whatever powers Bob Parr possesses as Mr. Incredible only become that much more vital when he's able to be honest with his wife Helen/Elastigirl and their children, Violet and Dash. When he's first brought to the tropical Nomanisan island by a mysterious benefactor who turns out to be his enemy, Mr. Incredible isn't able to stop a massive, fast-thinking robot on his own; once that robot comes to the mainland and tries to wreak havoc, Mr. Incredible can only stop it with the help of his whole family.

Even in the Pixar films that aren't explicitly about family, there's a sense of valuing the community over the individual. Cars, for all its flaws, is largely about Lightning McQueen coming to accept that he alone cannot be a great race car; only with the help of other people – er, cars –can he achieve his goals. The year after, Bird's next film, Ratatouille, depicted the portrait of a brilliant artist, but also shows that unlikely artist — a rat named Remy — struggling to accept that culinary perfection cannot be achieved alone and that treating his rat family as slobs comes at the cost of losing their love and kindness. When Remy's human cooking companion Alfredo Linguine reveals to other humans in the kitchen of Gusteau's Restaurant in Paris that a rat has been pulling off plenty of incredible dishes, they leave for good. However, Remy can only impress a room full of Parisian diners and a fearsome critic with the aid of his fellow rats, not by himself.

In the last decade, the theme of family has been even more present in Pixar's films. There's Up, in which a grouchy old widower becomes a surrogate father figure to an upbeat yet awkward little boy decades after he learned that his wife couldn't have children. And there's Brave, which was explicitly about a mother-daughter relationship, having been derived from the real relationship between the film's original director, Brenda Chapman, and her daughter. (You could argue that Brave, as admirable an effort as it was, didn't work as well as it could have because Chapman was booted off the project, and a personal project became something more perfunctory.)

In the exemplary Inside Out, director and co-writer Pete Docter expanded on the themes in Monsters, Inc., personifying various emotions inside the head of a teenage girl going through a traumatic period in her young life. That film's lead Joy, voiced by the wonderful Amy Poehler, is as much a parental figure to young Riley as her own parents are; when Joy sees memories vanishing in Riley's mind, she's heartbroken in the same way that a parent is when seeing their child change in front of them, growing apart as much as they grow up. This, in effect, is the lesson that many of the parents and surrogate parents have to accept by the end of a given Pixar story: the value of letting your kids go.

The Joy of a Surrogate Family

Finding Nemo, even more so than its 2016 sequel Finding Dory, handles the dual issues of parenthood and letting go delicately and precisely. Some beats of the relationship between Marlin and Nemo — right before Nemo is taken away by a human to live in an aquarium at a dentist's office, he tells his overprotective dad "I hate you" — feel true to the characters, even as other films and TV shows might try to echo similar gut-punch moments. Although the film separates Marlin and Nemo early, we still get to see how they act as father and son, just with different characters.

Marlin's relationship with Dory, although the two are voiced by actors in roughly similar age ranges, never approaches romance; Dory, especially as seen in Finding Dory, is less of a surrogate mother than a sister to Nemo. To Marlin, Dory acts like the daughter he never had; even before Marlin's desperation is so intense that he accidentally calls her "Nemo," the clownfish is acting like an overly assured parent, refusing to listen to her point of view in favor of his own choices. He's only able to let go of his control issues with her at the worst possible moment, when they're stuck in the massive mouth of a whale.

Nemo finds himself with the kind of surrogate father he dreams that Marlin would be like, the tough-minded aquarium fish Gill (Willem Dafoe). Gill, basically the inverse of Marlin, is confident that Nemo can escape his watery cage and get back to his father, by being flushed down a drain and eventually back to the ocean. (The very thought of this idea, you have to imagine, would make Marlin pass out in fear.) Gill's assurance, even in the face of certain death, is what allows Nemo to gain his own confidence, helping save Dory from the clutches of a fishing boat and receiving his father's blessing to do so.

Upon rewatching Finding Nemo after 15 years, what is perhaps most surprising about the third act is how much the emotional catharsis revolves around Dory, not Marlin and Nemo. The latter two characters, of course, are going to reunite at the end in a happy moment. (There's only so much heartbreak you can find in a Disney/Pixar animated film.) But the true low point isn't when Marlin thinks his son is dead, or when Nemo thinks he's stuck in an aquarium or in the clutches of an obnoxious little girl for good. It's when Dory believes she's been abandoned by Marlin, as her heartbreak supersedes the short-term memory loss she's suffered since her youth. "I don't want to forget!" Dory exclaims, after Marlin believes he's lost everything. "I remember things better with you." Though it's not the only lesson Marlin learns by the end of the story, this is the core moral of Finding Nemo: his family can be more than just him and his son.

Though it takes Marlin a little more time than it should to accept this, he is a better character when he's able to accept others, instead of shutting them out. By the end of the film, he realizes that Nemo can do more — and should do more — than he ever thought possible. He accepts that Dory has value in his life, just as he learns not to condescend to everyone around him. In this way, Finding Nemo feels awfully similar — not in a bad way — to other Pixar films that depict the value of a cobbled-together, makeshift family as opposed to biological ones. (The Incredibles may be the rare exception in this case.)

Finding Nemo isn't quite the daring emotional marvel that Pixar pulled off in the latter half of the 2000s, but its presentation of letting a family supersede any one character's neuroses is the finest distillation of Pixar's filmmakers embracing their patchwork families in cinema.