/Film Interview: 'A Field In England' Director Ben Wheatley

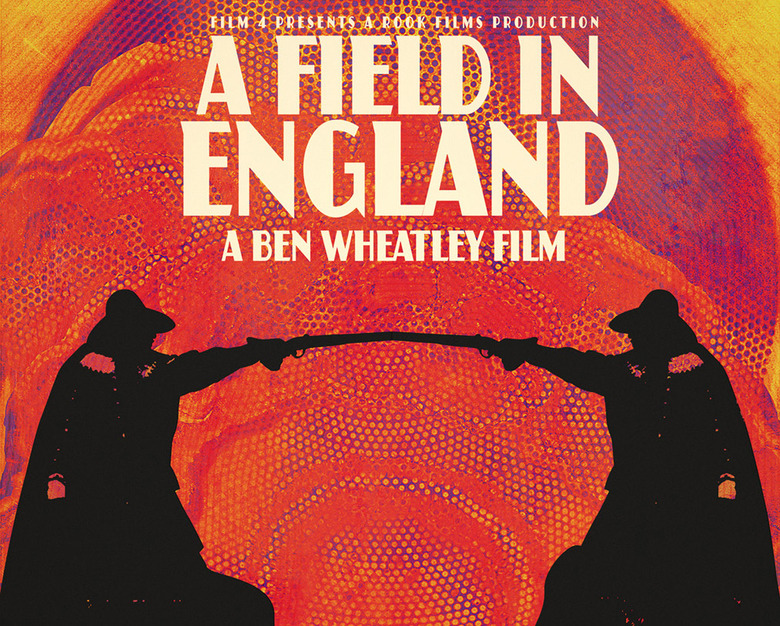

I think Ben Wheatley, together with partner/writer/editor Amy Jump, is one of the most interesting directors working now. He makes genre films that are, thanks to Jump's scripts, very sharp and perceptive, but also very weird, and not at all afraid to push audiences out of their comfort zones. A Field in England is emblematic of the films they make together. It's a story about a few men during the English Civil War, some coerced to work for others, and how they all come together in a mad frenzy of power and influence.

I spoke to Wheatley a while ago about A Field in England, and for those who have seen the film, which is in US theaters and on VOD now, you might be happy to know that he explains a few plot points that might seem pretty obscure. But he also talks about why he doesn't like explaining story elements, within his films or in interviews, and what he and Jump had in mind for audiences as they were putting this story together.

This movie leads me to a lot of ideas about how something in the earth, buried in the ground, could be part of horror. To begin, can we talk about story's approach to the fairy circle and mushrooms?

We came across it through research, the mushroom circle stuff. I thought that was always really interesting, the folk idea being that if you go inside a mushroom circle you can be trapped in there. Then, apparently, it takes four men and a rope to pull you out. When you come out, you'll find that time has passed differently, you could have perceived to be in there for ten minutes, but you've been in for four months or something. That's a really interesting setup, that you're trapped in a place, and it doesn't look or feel like you're trapped. So that was kind of the beginning of it.

But also, I'd wanted to do something, Amy and I had talked about doing something that was in a field, or just in a small space. And I'd seen a film years ago called Contact, not the one you're thinking of, about soldiers patrolling on the border with Northern Ireland during the Troubles, and it was just these five guys on patrol, dealing with it day to day, never seeing anyone. it's just all fields and stuff. I thought that was kind of interesting, but then this also comes from films like Dogville, and then Lifeboat, movies that have given themselves a set of parameters. That was kind of it, really.

The folk stuff we just started researching a bit more and found that there was this rich background. I guess we made that leap to magic mushrooms by reading about other stuff that had to do with psycocylin that was going on at that time, like grinding it up and blowing it into each other's faces, which was pretty wild. People eating stuff, thinking they were possessed by the devil. And I"d been thinking about ergot as well, the fungus that grows on wheat, which is incredibly psychedelic, so research into that and synthesized LSD... and this didn't happen so much in the US, but in the UK there were instances where someone would bake ergot or something into a loaf of bread, everyone eats it, and then go out of their gucking minds. Anyway. That kind of thinking.

The films features elements such as the magic mushroom and the rope, which you just explained, and also several visual tableaus, which very clearly reference a visual tradition, but which aren't explained to the audience. Why do you choose not to explain some things?

I'm not a big fan of exposition, I hate explaining. I think it's really boring. I like that feeling of being... having to think and work out what things are. It's kind of artificial to sit here and have to explain the ins and outs of stuff — I don't think it's important, otherwise I would have put it in the movie.

What we wanted to do was create this environment where you felt like you'd just been parachuted into the past, and the people around you are already involved in it. They don't talk about it, why would they? It's like the news now, if you miss the beginning of a story and you're looking at a newspaper, you don't know what the fuck is going on. And now they never recap. I find it frustrating in movies where everyone stops to explain stuff. I think that breaks the reality of the film, and the experience. Sci-fi movies in particular, they do this a lot. A film I enjoy, Minority Report, has Cruise always acting like everything is really surprising in that movie! (laughs) Like "oh, look, cars are driving on their own!" But you know that! You've been here before! So that's all part of it, that you're just dropped into the past.

As you and Amy are scripting, is there a stated mandate to set things up so that you can avoid exposition?

Yeah, in our other films like Kill List and Down Terrace we'd written sequences of exposition and shot them, then pulled them out in the cut to bring the films down to their barest burden, so it's just the story. In this one we didn't even do that. We've come this far down the line that this script is the most efficient translation from script to screen we've done. I think we lost like four lines out of the whole thing in the end.

You've done a lot of improvisation on films in the past –

You've done a lot of improvisation on films in the past –

There is no improvisation in this film, maybe one line.

Was that due to a tight schedule?

No, you can't improvise in the past, story-wise, unless you're working with actors who are all academic historians. Because every word you use has a date stamp on it. So saying something like — well, I'm sure there are other mistakes in the script, but there's one line that mentions envelopes. But an envelope is not something that existed, it didn't make the dictionary until about three years after the film is set. "Envelope" is a pretty innocent-sounding word, but you just don't know. I had a thing with the term "freelancer." A freelancer was a knight, a guy with a lance who goes out for hire. So you think OK, that's fine, I can use that, right? But no, it's from a French book that was written in 1820 or something, that author made it up, so it sounds right, it should be OK, but you can't use it. So improvising is a nightmare in that sense, and you don't want to put that on the actors. They just can't say so many things.

There's a terrifically dense language in the script, you give actors a lot to work with, and a lot to deliver. How do you cast a film like this?

It was cast in the same way the other films were cast, which was more that there were people who we wanted to work with, and I asked them. If they could do the dates we need for the film, then the script was adapted slightly to fit them, to make sure it fits their range, and what's good about them as actors. So it's a bit of a reversal from what usually happens, when your'e casting, but it means you're always going to get the best out of them because you know what they can do.

You seem to me to be one of a group of people who approach filmmaking from a relatively pragmatic point of view, where there are certain ideas, and various financing out there, and you try to put them together without being too precious about how it works. Would you say that's accurate?

You seem to me to be one of a group of people who approach filmmaking from a relatively pragmatic point of view, where there are certain ideas, and various financing out there, and you try to put them together without being too precious about how it works. Would you say that's accurate?

Yeah, I mean, there are certain building blocks of drama in any story and in what you're saying that boil down into simple things, and you can make them more complicated as you scale up. But what actually happens in movies, those dramatic systems of people clashing, agreeing or disagreeing, falling in love or not, there's not millions of them. So to not be making a film because you couldn't get millions and millions of dollars to build a giant castle or some bullshit like that seems insane. Some bigger budgets are appealing, of course, and I think there'll come a time when I want to play on that scale. But there's still plenty of work to do on the lower end as well.

I never saw low-budget film as a stepping stone towards Hollywood stuff. There's a lot of pleasure to be had in low-budget, starting with the fact that you're in complete control of it. That's it, right? If you're the greatest film director in the world and you've taken $60m off someone, you've still got to answer to someone about it unless you're James Cameron or something. That's the second priority, and you have to have your priorities right with respect to why you're int he business, and what you want to say.

I can't envision some of the things you want to say, based on your previous films, fitting will in $60m movies, and also allowing you the freedom you've had.

Well, I make ads, you know. I make ads for aggregate websites that'll help you find the cost of one thing over another. I'm not difficult, or set in my ways as an "art house film director." I've got a broad palette and things I want to do, so in terms of making big-budget stuff, one day that'll happen. The way it kind of works is that you get offered stuff that's like the stuff you've done. So the only way out of that is by making something new that's unlike other things, and that opens up more avenues.

Would you say that the films you've made so far explore any one concise set of ideas or themes?

I think that — I don't know, I approach it differently on different days, and some days I think they're very different, all the films, and on other days I like to imagine them as all in one universe.

Is that a modern thing, the one universe approach?

Not really, it starts with Vonnegut, doesn't it? Or Stan Lee. (laughs) In the '60s. It just makes it easier, it makes the canvas broader, and so easier to point at some ideas if you think about it like that.

You've made a passing reference to an HBO project that could be a prequel to something. Is that related to this, or Kill List, or...?

I'm doing a script for HBO, yes, and it might, I don't know, it might tie everything together. But I don't know. It's, how to say it... It'll tie it all together within the bounds of legality. That's the ambition of it, but it might be "bound" with a very small "b." Thematically, at least, it could all fit within that world.

I see in this, and Kill List, and Sightseers, things about masculinity, and how the desire for power affects people, especially men.

Well, you end up seeing things from your own perspective, it's inevitable. But it doesn't mean that we're not trying to not do that. I've found, with Amy [Jump, writer and editor], working and scripting this stuff, it helps push it away from just being about middle-aged white fat men. (laughs) And the thing that Amy brings is that she's editing them as well, she's not just writing. When you say that out loud, you kind of wonder why the fuck that isn't being done more often! Because people talk about editing being the final draft of the film, and it is, so really want the writer to be involved in that. It helps the whole thing.

How do the two of you work together?

Is it Death Trap, the film with Michael Caine, where they have the typewriters next to each other, and they collaborate? Not like that. (laughs) You know, we've been together for years, and I used to find it kind of depressing that my writing would usually be crossed out (by her). But now I've come to terms with it, she's beaten me, after years, into submission and acceptance that she writes a lot better than I do. So that's how our collaboration works, usually.

You can hear more from Wheatley about A Fiend in England in the extensive behind the scenes footage we posted earlier, as well.