Interview: 'Nightcrawler' Director Dan Gilroy On Manipulation And Ditching The Character Arc

It's rare to see a directorial debut that is a total home run, but that's Nightcrawler in a nutshell. The film's writer/director, Dan Gilroy, is not, however, some rookie who got lucky. He's been a screenwriter for years, with credits on films like The Fall, Real Steel and The Bourne Legacy. He was the writer on Tim Burton's aborted Superman film with Nicolas Cage. And his family is in the business, too: brother Tony has his own screenwriting career, and is director of films like Michael Clayton and Duplicity; brother John edited films such as Warrior and Pacific Rim; and his wife Renee Russo needs no introduction.

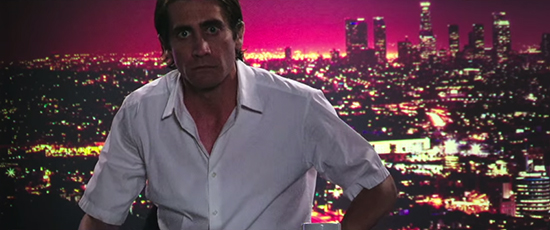

They all are part of Nightcrawler, in which Jake Gyllenhaal stars as a man who finds himself uniquely suited to compete in the world of independent cable news contractors. Gyllenhaal's character Lou Bloom is taught the "if it bleeds it leads" axiom early on, and he runs with that concept. Renee Russo plays Nina, who buys Lou's footage and helps shape his new career. Tony Gilroy produced, and John Gilroy edited.

I sat down with Dan Gilroy to talk about the film, and admitted that, as horrible as the guy can be, I'm somewhat envious of Lou's pure drive to succeed. We talked about sociopaths, the liberation that comes from ditching a traditional character arc, and the beauty of Los Angeles at night.

Note: This interview is not spoilerish in a nuts and bolts sense — you won't be given the plot. But we talk about the broad scope of the character and the concepts behind the film. So bookmark this one to return to after you've seen the film if you'd prefer to see Nightcrawler cold.  As a writer, do you start with the situation, or the character?

As a writer, do you start with the situation, or the character?

I normally start with the situation. In this case the situation was there, because I had uncovered this world, but I didn't start writing it then. I stepped back from it, and over a period of time the character started to develop. And when the characters started to speak I realized the movie wasn't about the world, it was more about the character. And so it became more of a character study than I usually do, which felt really great to do.

The script upends some technical "rules," such as the notion that the main character should change.

There's no character arc! When I started to write the character I realized, "this guy isn't going to change." Every film you're commissioned to write is all about an arc; usually the arc is that the world creates a change in the character, usually for the better. To not have an arc, the messages and ideas in the film became more prominent. The character is plowing through boundaries, and keeps going. So the boundaries become very clear, the things he's crossing. And the focus on it is the world bending morally to what he's doing. At the end, allowing him to succeed at what he has done, and celebrating his success. Raising questions: what does it say about us that we allow something like this to happen? It opened a lot of doors that a traditional arc doesn't.

What was the most important thing to communicate with this character?

I believe that people like Lou are increasingly rewarded for what they do. I feel that in today's world you will often find people with some sociopathic tendencies who are succeeding on a corporate level. I feel that the world is increasingly about the bottom line, and not so much about human respect or human dignity. In that regard, people who care about other people will not be in a position to make choices and do things that other people who they're competing against will get to do. And I feel that the world is increasingly reduced to transactions, and that the human spirit is shoved aside to the point that — well, Lou understands that the world is about the bottom line. And accepts it! He has no family, and no connection to anything. It allows him to thrive, and to fully embrace the uber-capitalist concept, the ultimate hyper-free market. Which I feel is increasingly the world that we live in.

He very rapidly transitions from labor to management.

He is uniquely suited to management because he SO believes in the system. He believes that our experience on this planet, as sentient human beings, can be reduced to a climb up a ladder. To the acquisition of a job title. People who reach upper management in corporations or business — not all the time, there are many hard-working people who deserve everything they get, probably far more than not — but there are people who, like Lou, embrace the idea that it doesn't matter what you do as long as you get it done. And I think that suits people for management in a lot of ways.

I'm almost jealous of Lou, in that he so forcefully expects to get what he wants, and that it does all fall into place for him.

When I was writing Lou, I thought "wow, it's almost a dream that you could go through the world, do what you want, and not worry about the consequences." Ultimately it's hell, because I believe when you don't care about other people you're living in utter hell.

But all the time that I invest in thinking about my relationships with other people, my relationship with my wife, my kids, people around me, people having problems, I worry about them, I can't sleep at night. Lou has none of that! He is utterly unburdened. He wakes up every morning and it is just "what am I doing for me?" He doesn't worry about anybody but him. And that is probably wish-fulfillment in some ways, for some people whose lives are consumed by worry and legitimate concern about people they love. Lou has none of that, and all the time that we invest in that, he invests in himself. I think it works much to his advantage.

I wonder about an endpoint, or a crash for Lou. I've found myself thinking a lot about whether he could become a Rupert Murdoch figure.

I believe he does. When I wrote it I did. I believe the people who get caught are the dumb ones. That the true sociopaths, the smart ones, you never see them. They live and die amongst us and you never know they're true sociopaths. Because a sociopath is not just someone who doesn't care about human emotion. They're someone who understands people to the point that they can manipulate them to an extraordinary degree.

Lou is a wonderful manipulator.

He understands people the way a lion understands a gazelle. Everything about them. There's nothing he doesn't know about them. So, actually, I always thought it was ironic when Rick says "your problem is you don't understand people." Lou understands people to a degree that goes beyond anything Rick could imagine. On an animalistic level.

One line really stuck out for me: Lou telling Rick "get out of your head, it's a bad neighborhood." It sticks in part because I project it onto Lou as well.

Yeah, it is a bad neighborhood in Lou's head.

That line seems so specific; does it come from a particular place?

It's very funny you ask about that line! That line came from a friend of mine who's a producer, a gentleman named Jon Peters (Superman Lives producer), and I worked with him a number of years ago. Jon used to say that sometimes. "Get out of your head, it's a bad neighborhood!" And it always stuck with me. I loved the line, so I'll credit Jon Peters with that line. And proudly so, I love the guy.

I love that the process of making a film about an isolated sociopath was a total family endeavor.

I love that the process of making a film about an isolated sociopath was a total family endeavor.

I felt so supported to have a brother on either side — particularly one brother who started out as a writer and became a director. There was nothing I was experiencing that Tony [Gilroy, producer] couldn't help me out with. And then my brother John is an amazing editor and I was working with him on the other side. So I feel supported on that side, they're both extraordinarily talented. Then I had Renee [Russo], my wife, on set working. So it felt very comfortable to walk on set. I mean, there was still a lot of tension and stress. We're working under...we didn't have a lot of money and days were tight. But in the stress of it all it was nice to know that I was supported by people who I can trust. John was cutting as I went along, and he had an assembly [by the end] then we came in and worked on it afterward. We had a 16-week post. He was instrumental in crafting key, crucial sequences.

What was the most difficult scene to lock down?

There were two. One was when Nina was directing the story, telling the anchors to sell it harder. We had to cut and compress, and John compressed it in a way that was just amazing. And then the shootout and the chase, the way we crafted that and the way John put it together, the pacing of it and the angles we chose, I felt it showed a master hand on John's part.

Was the script solid when Jake came on?

Script was written, Jake didn't change a word. But Jake is my creative and collaborative partner in a lot of ways on this. I wanted to work with him, to bring his energy and creativity to the part. So we decided in our first meeting that we were going to rehearse. So we did that for months beforehand.

I would go up to his house and the rehearsal process was really one of exploring and trying, and not being afraid of something not working. Jake is fearless that way, Jake is utterly fearless and wanting to try. I think directors can only be so lucky to work with someone like Jake if you're open to it. If you're willing to collaborate and share, for lack of a better term, the power of directing with an actor in the sense of allowing them to explore and do things, try things and do different takes. Having those in the can so in post you can string together something that is unique. Jake blew me away. Even now when I watch his performance I always see something different that he was doing. He's a supreme talent.

It seems like you're in a wonderful position, working with him and Renee, to get something potentially very difficult — like the date sequence.

The date from hell! That came from a lot of rehearsal and finding layers to the scene, realizing that she was vulnerable, and Jake realizing different points. It was like a chess game. That's how we approached it; we shot for like 12 hours on that scene.

How do you direct a movie that is so heavily bound to characters in cars?

How do you direct a movie that is so heavily bound to characters in cars?

Cars are hard. A lot of that was working with Robert Elswit. We had a digital camera, the Alexa, and it's just figuring out — you put these trays on either door, and you figure out how many cameras you're going to have at any given time. You want to put a camera on the hood at times, but you don't want to block the driver's view. There are times Jake would be driving when the camera's in front you have concerns; can he see or not? So the mechanics of figuring out what series you're going to do shots in — basically saying ok, this angle first because there's a right hand turn, or whatever, then just working out a shot list with Robert.

How often was Jake driving?

Jake was driving probably 75% of the time and he was getting towed (on a process trailer) probably 25%. We wanted Jake driving as much as possible because there's a gravity to driving. And Jake is an excellent driver! Incredible driver. That thing at the end where he threads the car between a couple things, and does the pull, that's Jake driving. He's a superb driver, I don't know if he took driving classes, because he's really good at it.

I found myself excited that Nightcrawler proves the nighttime city picture has got some kick left to it. I'd like to know more about how you and Elswit set the tone of the night shoots.

We wanted to show LA in a way that it's not traditionally shown. A lot of times LA is desaturated, and cement and freeways, and downtown. We wanted to capture more of the electricity of the place, the wilderness energy of it, the desert light that you can see forever.

So we did a lot of wide-angle, we were opening up the camera to capture as much light as possible, and really bringing in a lot of detail in the background. It was shooting in places that you don't normally see, allowing neon signs to register, doing as much deep focus as possible, never really using shallow focus. We wanted your eye to go as far back into the frame as possible. And we wanted to shoot LA to make it look physically beautiful as much as possible, to be honest. I find it to be a physically beautiful place in a lot of ways, between the mountains and the hills and snow and ocean.

We had 80 locations in this movie, we shot all over LA. In 27 days, of which 24 were nights, in a row. We were on nights for weeks, it was a wild energy. LA at night is amazing, driving around LA at night there's no traffic at all, ever. A lot of films go downtown. We didn't go downtown; we never shot anything downtown because everyone does, and we wanted to show a different part. And Robert lives in Venice, we shot that scene just blocks from his house. He walked home that day, he loved it! But we would drive around for months before, we did a lot of that to find locations.

For many people, awareness of this movie came out of the blue with that Craigslist promo. Whose idea was that?

For many people, awareness of this movie came out of the blue with that Craigslist promo. Whose idea was that?

It was Jake's idea to shoot the elevator pitch speech different times while we were shooting the movie. So that was Jake's idea, which I loved. We started just shooting that whenever we could, we shot like five versions of it. We cut it together, put the music to it, and Open Road's marketing people very wisely found Craigslist as the place to launch it. So that was their idea, and I loved it. Great idea! Open Road I think is doing a terrific marketing job. It really opened the door for us in a lot of ways.

***

Nightcrawler is open in theaters today, October 31.

NIGHTCRAWLER is a pulse-pounding thriller set in the nocturnal underbelly of contemporary Los Angeles. Jake Gyllenhaal stars as Lou Bloom, a driven young man desperate for work who discovers the high-speed world of L.A. crime journalism. Finding a group of freelance camera crews who film crashes, fires, murder and other mayhem, Lou muscles into the cut-throat, dangerous realm of nightcrawling — where each police siren wail equals a possible windfall and victims are converted into dollars and cents. Aided by Rene Russo as Nina, a veteran of the blood-sport that is local TV news, Lou blurs the line between observer and participant to become the star of his own story.