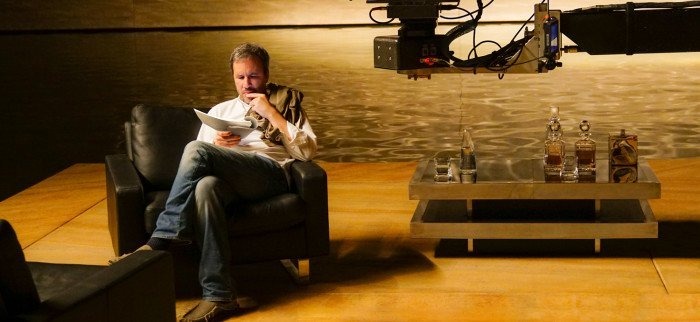

'Blade Runner 2049' Director Denis Villeneuve On Building The Future And Taking Ridley Scott's Advice [Interview]

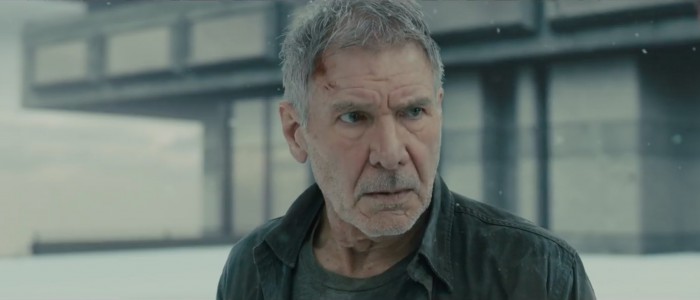

With Blade Runner 2049, which arrives in theaters 35 years after Ridley Scott's classic, Denis Villeneuve has pulled off no small feat. The filmmaker behind Arrival, Incendies, and Sicario has made a sequel that doesn't stand an inch in the shadow of Scott's masterpiece. He's made this iconic depiction of the future feel as new and as awe-inspiring as the 1982 film.

Just like the original, every frame of Blade Runner 2049 is a visual marvel, which should come as no surprise considering the talent Villeneuve surrounded himself with on his largest film to date. The director reuinited with legendary cinematographer Roger Deakins on the sequel, and together they've again crafted such dense, emotional and dazzling images and created a hypnotic atmosphere. When we spoke with Villeneuve, he told us about their work together, what original Blade Runner director Ridley Scott told him to keep in mind, and why Blade Runner 2049 is a more hopeful story than the original film.

I think this movie is better than anything I could have ever hoped for from a Blade Runner sequel.

Thank you very much. I will say that I had that feeling when I read the screenplay, because me, I was not convinced at all. When they said to me that they wanted to make a sequel to the first one I was like, "Really?" I had strong apprehensions until I read the screenplay, when I felt okay, there are strong ideas there, and they have potential to make a good movie. It's worth the risk. That's what I felt when I read the screenplay.

What were some of the strong ideas that appealed to you?

The thing is that I will be careful not to spoil things. There were several things like the power of memories. If as humans we are not in contact with our memories, what is left of us if we have no relationship with our past? The power of the past. In my previous movie [Arrival], there was I think that exploration of the power of the past and our self, how we are struggling with that imprint. How can we get free of that imprint from a subconscious point-of-view, but what if it disappeared? What's left of us? That, and doubting about your own identity, your own self and if your past is just a dream or real. All those questions I thought were a beautiful science-fiction question.

It's a beautiful story too. The original is very bleak, and so is this film, but I think it's more hopeful in some ways.

I think it's a sign of the times; as a filmmaker I feel that at the end of the day you make the movie for yourself, you make it for the audience – but you're the first audience. As a filmmaker, right now I need hope. I need to try to avoid to be cynical. I need to believe that, so I think that yes, there's much more hope in this one that I thought was necessary in our time.

You really didn't deviate much from the pacing of the original film. With all the moving pieces in the sequel, how was the experience trying to get the flow of the film right?

You really didn't deviate much from the pacing of the original film. With all the moving pieces in the sequel, how was the experience trying to get the flow of the film right?

It was long. That was one of the challenges. It's a more complex story than the first one, there is more twists and turns and more layers, not thematically but about the characters and storytelling. I thought that it required a longer time to tell the story. The rhythm of it, I really fought to protect the hypnotic sense of...[a] feeling of immersion that I was looking for. [Editor] Joe Walker and I, we really tried to – the first cut was longer, the cut I did and we loved it. We said, "Okay, it's there." We tried to protect the quality of immersion and tension that is coming out of the link of some shots, but to a limit so it's fast enough for the audience of today and protecting that pacing that I did love. It's a thing that Ridley loved, too. He said to me, "I am so moved that you brought that pacing to the movie, it's so respected."

It's long but there's some scenes that are like sparks and others that are like when you are following the blade runner and they are walking in the desert. Then those moments time is suspended but it creates an immersive feeling of strength, and the images that I feel that there's enough time to let the images on screen. I'll say I am working with the master. I deeply love working with Joe Walker. I don't think I will be able to work with another editor in my life. It's just that he's a very close partner and a close friend. I spent the last three years full-time with him. That is the human being I spend the most time with. Three movies back-to-back.

The film's sound is so immersive. What sort of soundscape did you and your collaborators want to create?

It all starts in the editing room. Joe, before he was an editor he was a composer, then he became sound editor, then he became an editor. We are working with the sound as much as we are working with the image when we are editing the movie. Me, myself too, it's like something that I always dream, my dream before when I was making indie movies. I had something strong in satisfaction with sound because I was feeling that it was something that was coming after. I was dreaming to do the sound as I was doing the image at the same time. To do both in the same time, and with Joe we started that process. The sound is as important. The sound design of the movie is done with the director's cut. When I finish the cut, the philosophy of the sound is there. Then of course there's a lot of work that the sound designer like a movie that we extended this idea more.

On this project, we made that logic a step forward by hiring a sound editor... Right at the beginning of the editing process there was a sound editor that started to design sound for us. We didn't edit the image and then they started the sound design. The sound design started at day one of the editing process. Even as I was shooting I remember [sounder designer] Theo Green came on board right away and talked about sound design. I was shooting the movie and he was starting to design sound. It was my oldest dream to do that. It's the kind of thing you can do when you have a movie with a lot of money. You can, as a director, experiment. The sound that took a year to do, and then [supervising sound editor] Mark Mangini came on board as I was doing the editing. It was a pile of work, so it's a long, long work that I supervised.

During your conversations with Ridley Scott, did he say anything about the original film that really stuck with you while making Blade Runner 2049?

Yes, there's one thing that he said to me that I really struggle with – that it was not about what I was about to show in the movie, but what I wish I will not show. With me, he said, you know, the first movie there's a lot of evocation and suggestion. We never see that other planets, we never see how the replicants are done, there's a lot of things that are suggested ideas, but the camera stays behind Rick Deckard or Roy Batty, and really at the human level, and that concern of his I felt. Ridley gave me total freedom, but I felt that he wished that I will respect those sacred territories and I try to honor that.

I trust by doing the same thing, by staying close to my characters and not trying to show the whole universe that I was allowed to show according to the screenplay but not showing – there are things in the script that I didn't do because of Ridley's wish there. Like showing a factory of replicants, for instance, and things like that. I would totally agree with him, you must not show that.

All the suggestions in the first movie are so powerful, too, especially in Roy Batty's final scene. They let your imagination run wild.

It's so much powerful! I feel it's so much more powerful to see the character in Close Encounters walking into the spaceship without seeing what he sees. It's so much powerful in 2001: A Space Odyssey to not see the aliens. For me, the best aliens of all time are in 2001: A Space Odyssey, and it's so much more fun when you don't see the shark in Jaws. I love that, yes. The power of suggestion.

Of course, I have to ask about your work with Roger Deakins. What were some of the earliest ideas you two had for the film?

Of course, I have to ask about your work with Roger Deakins. What were some of the earliest ideas you two had for the film?

The thing is that I need to say that I brought Roger on board day one. I said yes in the morning I met him at the dinner at his home at night, and I asked him right away, "Will you join me?" and he said, "Yes" with a smile right away. I knew he was dreaming to do science-fiction, to go back to science-fiction, and he was very excited right from the start. He came to Montreal and we spent several weeks together in the hotel room. Not a few months but several weeks together with storyboard artists where we drew the whole movie. You know when you storyboard, you basically rewrite the movie when you storyboard. You approach a scene and the visual, it's like a musician; you see the partition and there's a different way to interpret and it's the same thing with the camerawork.

Basically, we wrote a lot of scenes by storyboarding them – it's always the same that way – and we design the world together. We figure out what would be the laws, the sociological laws, the geopolitics, the climate laws, everything. There was a lot of ins in the screenplay but there were holes. The screenplay was of course, like any screenplay, filled with holes, and we needed to fill that. So I did a lot of work with him. I brought my ideas, we did research together, visual research together and we came with a ton of ideas, and Dennis Gassner, a production designer, came to Montreal too and we did all this work together. That was the foundation of the movie those working sessions with Roger.

What did the visual research involve? How did the characters influence some of the choices with light you two made?

I will say that it was about quality of light. I wanted the movie to have that kind of silver-like light quality of the winters that I know. To bring winter light for me was a way to bring something very intimate that I know very well into a universe that was not mine at the beginning, and how to invade Ridley's vision. I needed something very intimate and that was the quality of light, the winter light, and the writer responded to that strongly. Then you make research about different photographs that Roger took some, from photographers, like nothing specific, more like a very specific example of a type of light and colors; a lot of research on colors, on different type of atmosphere.

I will say that there was exploration for each character, what the light environment will be for each of them, like K's apartment was how to bring kind of a harsh, kind of neon light, kind of harsh light that is brutal and not kind for the eyes. Niander Wallace will have built a temple where he will control his own sunlight. Being blind, the light is more of a sensation, so doesn't need to lit the space. It's more like patterns that he will play with. There were all these laws. There was a long process of exchange with Roger. After that he helped me to protect this dream, going through the process of working with thousands of people.

It's strange, before I had the impression to direct, be a conductor in front of a little chamber orchestra of 12 people, and then I was in front of symphony orchestra. How to make each instrument with the right tune, you know? This was the biggest challenge – how to keep the dream intact. My respect for the directors like Ridley Scott just increased. How they are able to communicate their visions and staying in tact until the end. It's not easy to do, that was really difficult.

The opening shot connects to the original film's opening. Were there any other shots you and Roger Deakins wanted to reference?

The opening shot connects to the original film's opening. Were there any other shots you and Roger Deakins wanted to reference?

There's a lot of them. I would say just as an example, Ryan's character's silhouette, there was something in the silhouette of the Blade Runner it was difficult to imagine up that you're having a different silhouette than Rick Deckard. I was looking for a silhouette that will be a reminiscence of Rick Deckard and something that will also look like, for specific reason, like the vampire Norsferatu that comes into the fog. That was a reference. There was a lot of reference from a technology point of view, the shape of the spinners have evolved through to time but still they were a bit similar.

The architecture was inspired by the first movie that I used Syd Mead, the concept artist, who did the original movie and worked on some specific elements on this movie. There's a lot of little tiny references everywhere. The brand that argues was something that struck me when I saw the first movie, because the first time I was seeing a movie where 2001: A Space Odyssey had done it a little bit, but in Blade Runner, you had all that, Budweiser, Atari, all those present, and for me, it was very important to keep that alive, this link with reality. Because we were in the alternate universe, it gave me the possibility to use brands that were alive when they did the first movie, but like, Pan Am doesn't exist anymore, but I love the idea that it's present. So I made sure that with those companies were still alive in the movie today.

***

Blade Runner 2049 opens in theaters on October 6.